Reimagining Timber: Phantom Hands and AHEC at Design Mumbai

Image by Marie Chapuis

Parni Ray

25.11.2025

The search for responsibly sourced timber led Phantom Hands into a dialogue with American Hardwood Export Council (AHEC) and explorations with unfamiliar American hardwoods. After a period of experimentation and adoption of American hardwoods into some products, a more ambitious project emerged for Design Mumbai 2025 – an architectural scale pavilion built with American hard maple to showcase products made with American red oak and cherry. It marked a new trajectory for Phantom Hands. One rooted in curiosity, ecological responsibility, and expanded material possibility.

A Shifting Relationship with Teak

Often described as the “King of Timbers,” Teak - or Thekku, Tekke, Sagoon, Kyun, Sak, Jati - grows across the tropical forests of South and Southeast Asia. Historically it has been used to build boats, ships, doors, ceilings, pillars and beams, as well as beds and thrones. When the British arrived, they quickly recognized teak’s strategic value. Under colonial rule in India, it became the backbone of the push to expand the railway system, providing bridges, rail tracks, sleepers. The world’s first documented teak plantation, was establishaed in Malabar (today’s Kerala) in 1846. This marked a turning point in the global circulation of the timber. The machinery of the Empire soon made it a coveted international commodity.

Like most furniture makers in this part of the world, Phantom Hands’ (PH) relationship with teak is long and deep. Being steadfastly rooted in the region, using locally sourced, indigenous material has been a deliberate means of staying connected to traditional craft cultures and people. But the time may have come to rebalance this relationship. While teak will continue to hold its place at the heart of its practice, growing conversations around ethical production and sustainable forestry has led PH to consider alternative materials alongside teak.

Even as PH began exploring supplementary timber, they were introduced to AHEC, or American Hardwood Export Council. A non-profit trade body that promotes U.S. hardwoods like oak, walnut, ash, and cherry, AHEC advocates environmentally sensitive practices. ‘What we immediately liked about their team was their technical knowledge of timber and their open mindedness to the creative – not just commercial – possibilities of the material’, said Aparna, co-founder of Phantom Hands. AHEC’s strong ecological credentials, transparent supply chain and parameterised certification also made them a compelling partner, she adds.

An Evolving Dialogue in Timber

Phantom Hands’ collaboration with AHEC began in 2024, culminating in an exhibition in Bangalore. During this process, AHEC shared its technical expertise with the PH team, offering insights and training for the use of their timber. ‘From the very beginning, our decision to work with Phantom Hands was all about encouraging an accomplished and well-respected Indian furniture manufacturer to experiment with American hardwoods for the first time. We knew that this would be a challenge, given that their work was all in teak and that temperate American hardwoods not only look different, but behave very differently as well’, Roderick Wiles recollected. Rod is the Regional Director of AHEC's programmes in Africa, the Middle East, India and Australia/ New Zealand.

The organization had also introduced PH to Australian architect and woodworker Adam Markowitz. A small collection, Refractions, of furniture and lighting created with Markowitz, specifically explored the technique of layered wood bending, well suited to the AHEC sponsored red oak, cherry and maple. The precision and prolonged focus required for this method turned out to be a deep dive into grasping some of the native characteristics of the new species.

‘It was based on this experience that we decided to introduce cherry and red oak into our current catalogue – for x+l, INODA+SVEJE and especially the painted pieces in the Bawa Collection,’ said Deepak, who co-leads Phantom Hands. The move was well-weighed. The Bawa Collection consists of re-editions of furniture designed by the late Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa for his spaces. ‘A number of these were originally made with tropical hardwoods that are now difficult to source ethically or banned for export,’ Deepak shared.

This was not a small shift. Using non-indigenous timber meant moving away from familiar waters. Transitioning required understanding how best to celebrate and showcase them, rather than attempt to replicate the behaviour of local hardwood. This period of discovery thus marked an expansion in PH’s material vocabulary, also bringing in new surface finishes. It opened up a way of honouring South Asia’s craft legacy while responding to the ecological realities that now threaten it.

“We wanted to honour South Asia’s craft legacy while responding to the ecological realities that now shape it.”

Design Mumbai

Some months after, AHEC generously suggested presenting PH’s explorations in American hardwood in an exclusive Phantom Hands show. Rod reasoned, ‘After many months of experimentation, knowledge transfer and a successful collaboration, Phantom Hands were more than willing to adopt American hardwoods into their body of work and across their collections. Bringing this to Design Mumbai was an obvious thing to do, as it would give us an opportunity to show India’s design community what is possible.’ The second edition of the country’s first international event for contemporary design was to be held at the end of November 2025. It also presented the need for an exhibition set up, coupled with AHEC’s openness to suggestions for a suitable designer.

Bangalore based architect David Joe Thomas was brought on board. He had returned to the city a few years earlier to set up his own practice, NUMBER65, after having trained in some of the finest ateliers in India, Denmark, America and England. Aparna had come across some of his recent projects at the cusp of product and spatial design. There was an immediate recognition – a fellow inhabitant of the strict order of the grid; with an unusual additional quality of lighting it up with equal attention.

Due to the scale of the project, the initial plan was for David to produce the booth in collaboration with AHEC, taking cues from PH but without its production support. The brief was straightforward. The booth had to accommodate the eight selected PH pieces made with wood supplied by AHEC. Since it would need assembling at the fair site and dismantling once the event was over, the structure had to be light, transportable, and easy to construct and unpack. It also had to use maple, the last of AHEC’s three hardwood species from the donation, that PH had yet to explore more extensively due to limiting section sizes. Most importantly, the booth would have to reflect PH’s design aesthetic and history. This would involve connecting a geographically alien wood to the mid-century modernist moment in India that was the point of PH’s inception. Rod further iterated, 'It needed to show the beauty of the American hard maple from which it was to be made, but also not draw too much attention from the collection of furniture pieces that it housed.’

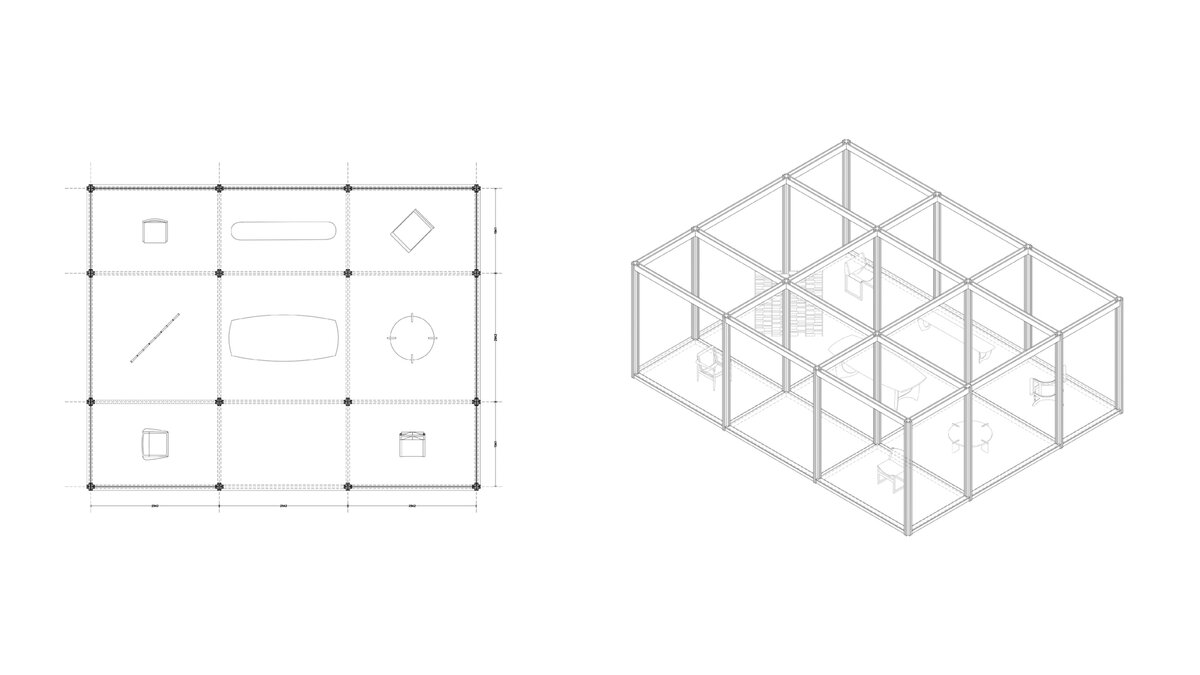

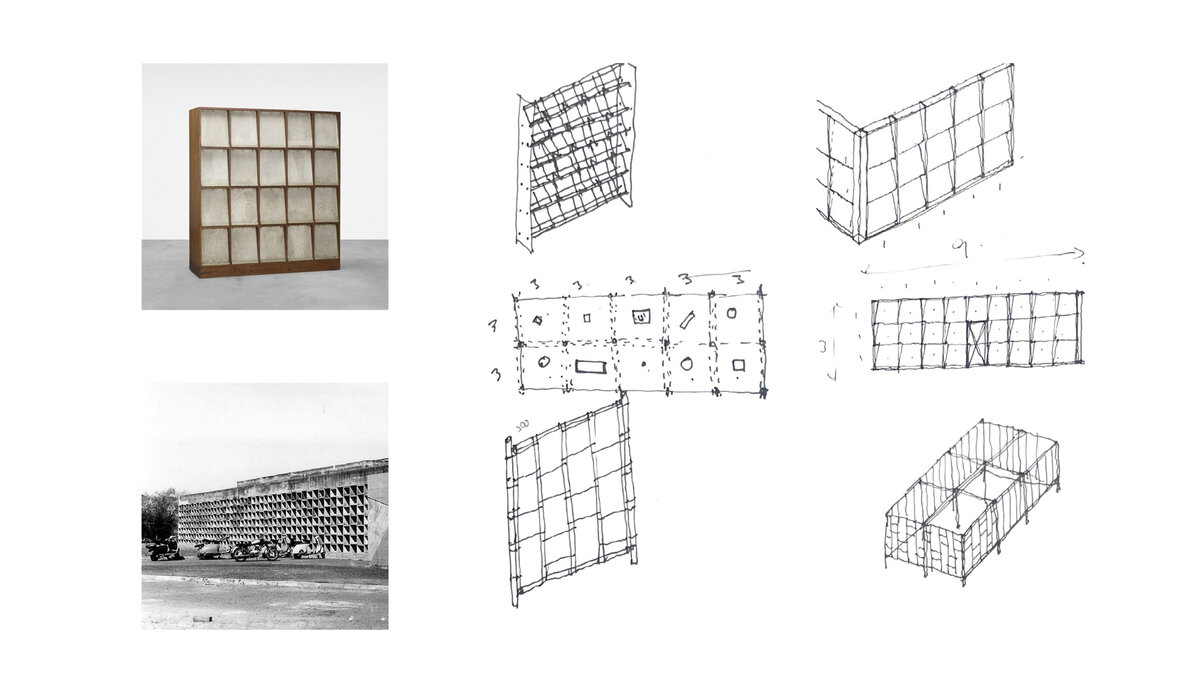

David started by looking at the furniture (and architecture) of the city of Chandigarh. 'That’s where the overall program and construction logic of the final pavilion comes from, including the joinery style we use,’ he pointed out. After an initial phase of research he proposed a nine-block modular structure - all but one, holding a piece of furniture at its centre. 'Fairs are busy places. My intention was to provide a respite by creating an enclosed, visually quiet space,' he explained.

Making of A Pavilion

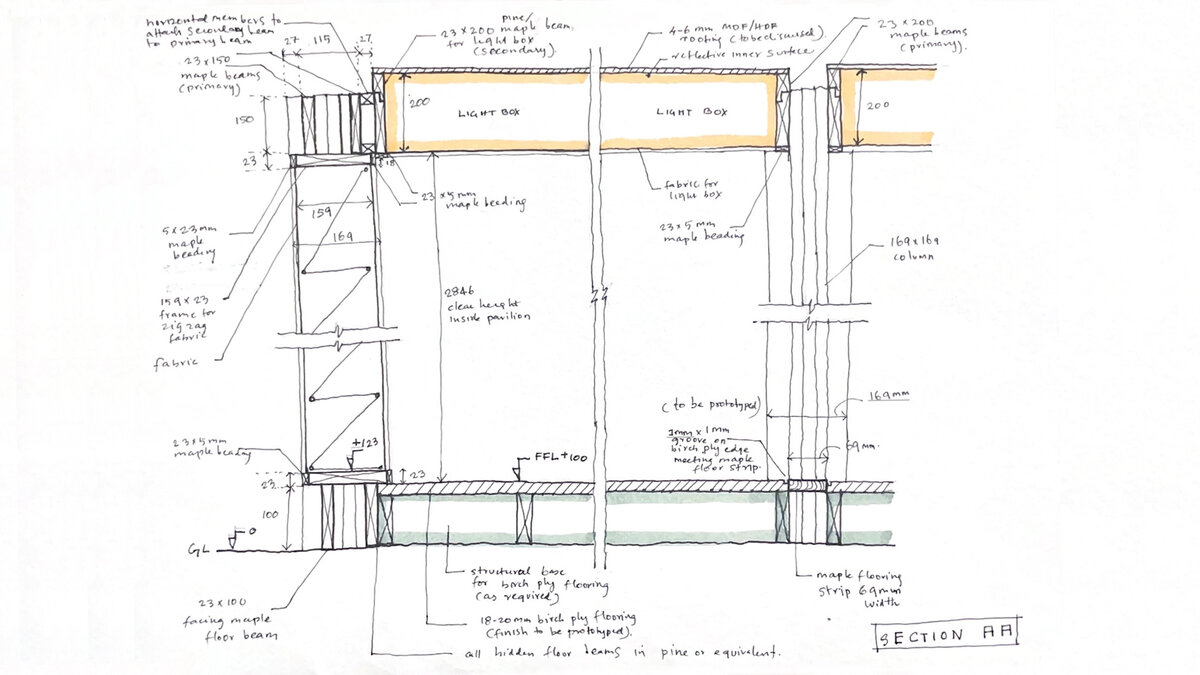

David delivered a clear, conceptual proposal; a strict framework; to then be inserted with one of 3 elements; a wall, a light box ceiling or a floor. The pillars and column were used in the exact post planing size, to minimise wastage. Each narrow plank was elongated using an elaborate dual system of temporary interlocking profiles and fasteners to enable the timber an afterlife beyond the 4 day span of the event – also a strong directive of AHEC’s. David proceeded to labour over a precise 2D geometry, imbibing all scales of construction with a thorough logic; from the size and location of dotted screw head caps to a complex joinery section all the way to the dimensions of the spatial grid itself. It was a process of constant triangulation within a very narrow error margin; any small adjustment at one scale; meant mirroring on every other. Aparna later reflected that, ‘It appealed to the closeted typographer in me, enough to disregard the challenges of scale at which PH can conceive and manage detail in production. It was irrational’.

For the wall unit, the primary interface of the enclosure, David was keen on drawing inspiration from the integrated concrete brise-soleil Corbusier used across Chandigarh and Ahmedabad. His sense was to echo this configuration now using cloth as the facade. ‘We felt that fabric would provide a textural contrast with all the hard timber in the booth’. It would also allow an easy flow of light within the space, he thought. ’I loved the idea of a jagged fabric wall and instinctively veered towards it, among others David had presented,’ Aparna recalled. It also referred to the repetitive, slanting face of the iconic bookshelf designed by Pierre Jeanneret,’ I was bitten by the bug to make it come alive in a way I hadn't seen before.’.

It was while envisioning how this could take shape, making quick trials with everyday materials from her art studio, Pors & Rao; and the skills of the PH tailors, that Aparna found herself becoming involved in the project. She approached the stepped wall structure by infusing a light weight fabric with rigidity, through the use of slim, tensioned steel cables and intermediate stiffening members. This enabled the delicate, gossamer-like muslin to take on a paper-like form, folding crisply around axes, while its anatomy remained discreet.

At first glance, David took to this expression, going on to select the ultra fine, hand spun fabric; incorporating the two straight outer surfaces and finely moderating their combined translucency to add, as he puts it, ‘a sense of mystery’. It changed the overall feeling of the design. The modest muslin, coaxed into strict tripartite symmetry, dramatically softened both the impact of the environment just beyond, as well as the internal monopoly of hardwood, on object and space.

Next was the management of the multi-directional and constantly shifting stream of light seeping through the stretched meshed cotton walls and ceiling. This was eventually resolved during ‘the iterative making and prototyping process, which PH is known for; one of the most exciting things about this project,’ David said. ‘It was undoubtedly a crucial part of the design journey. The various stages of prototypes allowed us to see how the materials interact with light, what the timbers look like under them or what the difference between having light shine on a piece of bleached or unbleached fabric is.’ All of this influenced the final decisions regarding how the booth would look and be constructed.

Finally for the floor, it was decided to use birch boards – which came closest to the colour and feel of maple, and was easiest to locally source in the special sizes that the project required. They were lightened in tone in order to maintain the visual continuity of construction lines as they travel across planes, running through the entire spatial frame.

When Everything Fit

But even as these exciting experiments unfolded, the sudden jump in scale (‘from the making of a chair to that of something closer to a small cottage’ as Aparna put it) and the compulsion to produce the pavilion in-house, took a real toll on PH. The booth was 63 square metres in volume, and constructing it as a full-size exhibition, with a tight deadline proved demanding. The quantum of precise joinery – hundreds – needed for several slim maple planks to transform into a solid beam along with the ambitious multi-tiered fabric wall requiring very elaborate, delicate fitting– all required unanticipated time and effort. Aparna says, ‘We also didn't have the experience to know better – now we do.’

'We had thought six of our carpenters for 4 weeks would be enough to work on the project,' Deepak said. 'But in the end, nearly thirty of them worked on it for four to twelve hours a day – in spite of contracting an external team.' Redirecting so many craftspeople to what was meant to be a low participation project slowed PH’s regular production cycle considerably. Deepak laughed as he recalled juggling delayed orders, customer concerns and logistical hiccups. 'We really have to thank all our customers from the bottom of our hearts for their support and patience during this time,' he said.

“The sudden jump in scale — from making a chair to something closer to a small cottage — tested every part of our process.”

After months of firefighting such challenges, came the time to assemble the booth structure. ‘I was very skeptical’, Aparna said. A species alien to our shopfloor, the natural movement of the wood that expresses dramatically over size, its impact on such a densely jointed construction was worrying.

This was compounded by the need for the less skilled among the workforce to pitch in and having to rely on templates- a much resisted system of verifying dimensions – versus measuring instruments. It was also impossible to oversee such a large team at the usual standards of rigour, where inspection plays a large part in the quality PH aspires to uphold. There were 14 hour shifts for everybody and not a single day off for 4 months, except three mandated State holidays. At some point, Aparna and Deepak had to take a leap of faith that all minds and hands on board, would self organise to reach the goal. An improbable prospect on all counts until the day of reckoning.

The perfect fit felt more than technical – much closer to a miracle. It was about a whole community, often at odds, finding a shared rhythm, connecting in a language beyond words and instructions. Aparna recounted, ‘It was such a jewel of a moment, all our uneven efforts became one seamless force of making. It was very moving to witness at that scale – that the care and commitment of the unsupervised phantom hand could be real and palpable.’ Rod couldn't agree more, ‘PH can be characterized by a dedication to thoughtful craftsmanship, traditional manufacturing techniques and furniture pieces that embody timelessness. All attributes that AHEC values extremely highly in a world where throwaway culture is becoming the norm.’

“In that moment of assembly, all our uneven efforts became one seamless force of making.”

A New Chapter in Wood

Timber remains at the heart of PH’s work, but this new chapter pushes the exploration beyond furniture. At its core, the collaboration with AHEC is an ongoing experiment, an attempt to understand what unfamiliar woods can do on their own terms and now to integrate them into the milieu of Indian furniture in an authentic way. It’s a learning curve, and the Design Mumbai stall became both its testing ground and its showcase – an ambitious, unexpected project that revealed how PH’s relationship with wood and designing with it, is evolving.