In Conversation With Phantom Hands Founder Deepak Srinath: The Origin Story

The Office Armchair X Leg from Phantom Hands Project Chandigarh collection. Image courtesy: Martien Mulder.

Parni Ray

23.10.2020

Many have made the Chandigarh chairs since they were first designed for the public offices of the city in the 1950s. Few among the independent carpenters typically commissioned to duplicate the designs - or the office babus commissioning - however, know their lineage.

Much like them, Deepak Srinath knew little about the furniture of Chandigarh or their ostensible creator, Pierre Jeanneret. He had just founded Phantom Hands, an online vintage furniture shop, in 2013, when a chance encounter with a pair of chairs set him on a journey.

Riding the wave of global interest in mid-century modernist design and Jeanneret, he decided to re-edit select pieces of the Chandigarh furniture oeuvre using traditional craft based production methods.

Parni Ray (PR): Do you remember when you came across the Chandigarh Chairs for the first time?

Deepak Srinath (DS): It was 2014 and we had just started Phantom Hands. At this point we sourced vintage items and shared a monthly catalogue of curated objects with people on our mailing list. We visited antique dealers and vintage shops across South India to find interesting items to showcase. It was on one such occasion that we came across a pair of Chandigarh office chairs.

PR: Did you know much about them?

DS: Not really, no. The antique dealer who had these chairs told me a bit about their history. He called them ‘Corbusier chairs’ and knew of their Chandigarh connection. Given how much we knew about Chandigarh architecture, we found it remarkable that we had never even heard of the furniture. So I quickly Googled it, and then fell down a rabbit hole (laughs).

Image courtesy: Phantom Hands Archive.

PR: What did you find?

DS: The stories of art dealers, galleries, and auction houses that had recently ‘discovered’ the furniture. The life story of Pierre Jeanneret. I read about the astounding prices the original furniture now commanded and the controversy surrounding these ‘heritage’ pieces being taken out of Chandigarh.

The international design community’s interest in mid-century European modernism peaked by the latter half of the 2000s. By the time I caught on, there was considerable talk, and even some notoriety, about ‘Pierre Jeanneret’s Chairs’. I was hooked. I read everything I could find about them. I even took a trip to Chandigarh, saw all the architecture and furniture, visited all the museums.

Image courtesy: Phantom Hands Archive.

PR: You liked the furniture…

DS: I really did. I admired their simplicity and clean form. As I learnt more about them, I came to appreciate their craft-based mode of production and the utilitarian ideal they represented.

PR: Much of this echoed with Phantom Hands’ aesthetic. Would you say their style was what convinced you to remake them?

DS: Partly, yes. We had discovered and admired a variety of Indian made furniture during this time – art deco pieces from Mumbai, Scandinavian inspired modernist furniture from the 1960s and 70s, George Nakashima’s furniture in Ahmedabad. All of these appealed to us aesthetically. Our engagement with the Chandigarh furniture, however, was different.

Image courtesy: Phantom Hands Archive.

PR: How so?

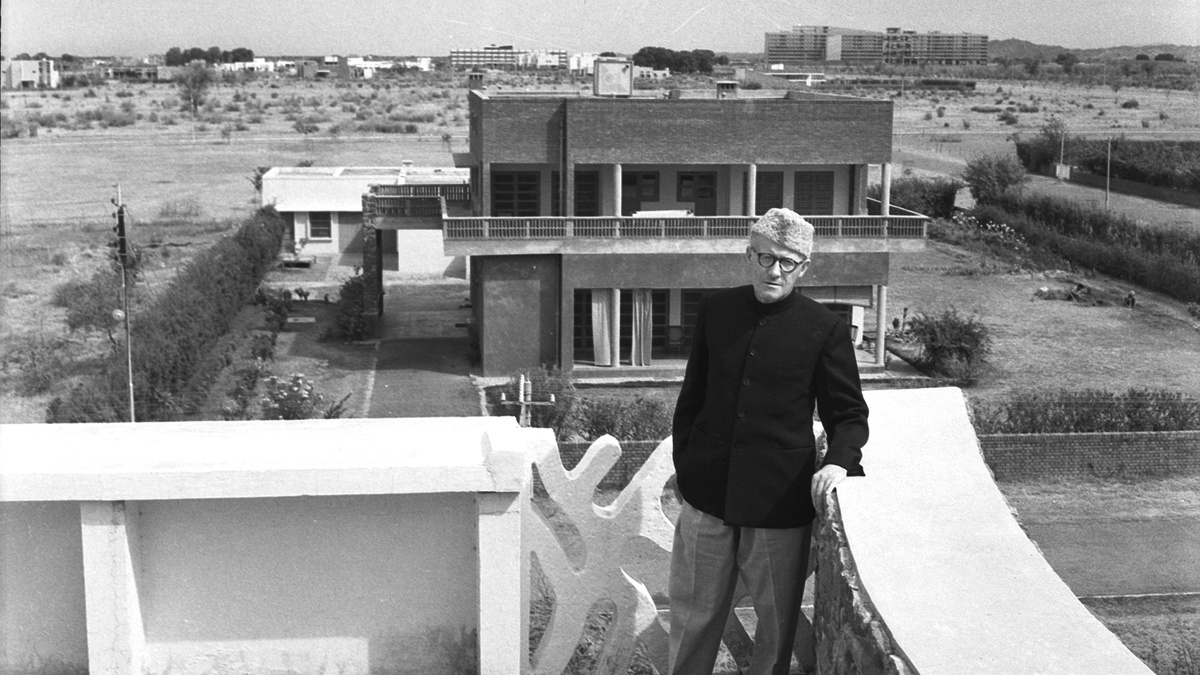

DS: For one, I had become fascinated with Pierre Jeanneret. I felt like his contribution to the Chandigarh Project (which included the furniture) had been largely overshadowed by the figure of Le Corbusier, the master modernist. Hardly anyone had even heard his name in India. I thought this a shame, because his work was undoubtedly crucial to the evolution of Indian Modernist architecture and design.

It was in this spirit that I thought about remaking the Chandigarh furniture. Even though there was obviously a market for vintage ‘Jeanneret chairs,’ no manufacturing company was remaking the chairs in 2014, which was surprising as re-editions are common in the furniture industry. Everything from Eames’ Lounge Chair to Le Corbusier’s own LC armchairs continue to be remade by several celebrated brands. So why not the Chandigarh Chairs?

Image courtesy: Phantom Hands Archive.

"It struck me that this was perhaps the first open source design project of such scale, anywhere in the world." - Deepak Srinath, Founder, Phantom Hands.

PR: Perhaps the possibility of questions over copyright and licensing? I am curious to know how you managed to deal with that.

DS: We obviously wanted to be completely above board, so I spent several months researching the history and design authorship claims of these pieces.

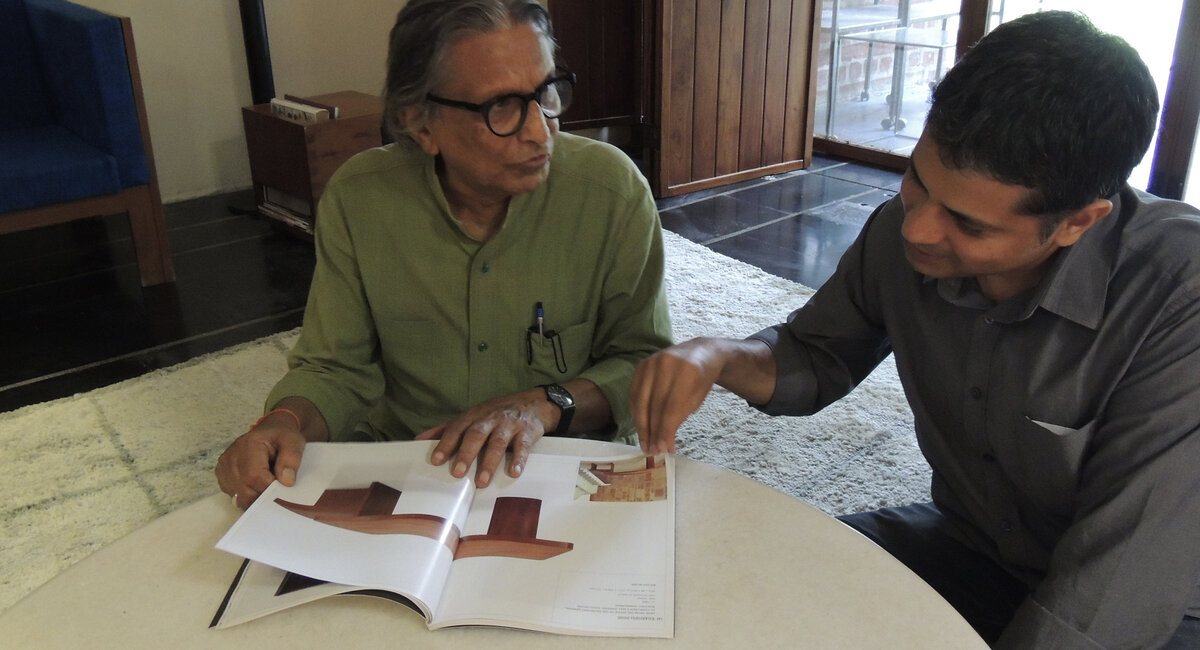

My quest began in Chandigarh, at the museums and via conversations with people who were directly or indirectly associated with that era. I was lucky enough to meet architects who had worked with Le Corbusier and Jeanneret during that period - people such as S.D Sharma, B.V. Doshi - to get insights on how the furniture had been designed and produced.

Next, I reached out to Prof. Maristella Casciato, who at that point was in charge of the Jeanneret Archives at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) in Montreal and was the foremost researcher on the architect's work.

I spoke to various intellectual property rights lawyers, archivists, scholars, and even Jeanneret’s family just to figure out who had legal claim over the designs. But no one could offer us straightforward answers.

Unsurprisingly, the copyright for the furniture doesn’t lie with Jeanneret’s estate, which meant we had to look further.

Image courtesy: Phantom Hands Archive.

PR: So you hit a roadblock at this point. How did you move forward?

DS: Slowly the pieces of the puzzle began to fall in place. Despite the claims around ‘Jeanneret Chairs,’ there are no documents clearly identifying him as the designer of the furniture.

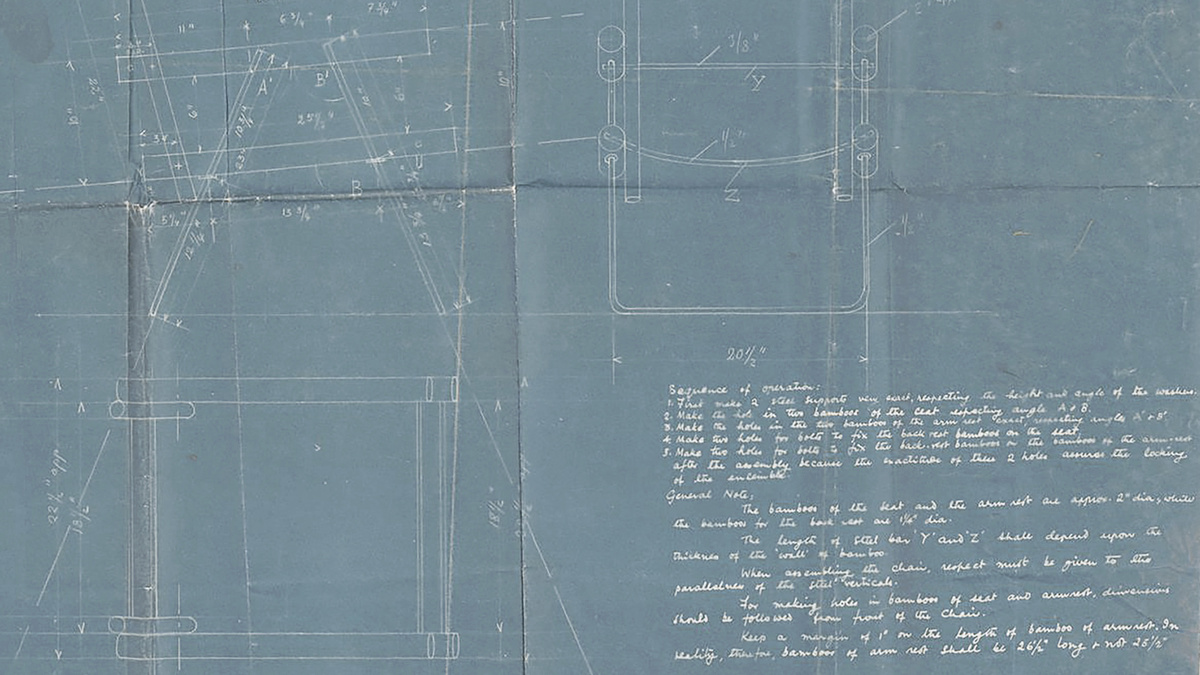

Yes, the designs are reminiscent of some of his previous work. And yes, he supervised the office responsible for the making of the furniture and almost certainly defined the signature design language. But clearly several others were involved in their actualisation - local architects on his team, craftsmen, model makers.

It is difficult to credit Jeanneret as the singular author of all the furniture produced in Chandigarh when all these other people clearly served authorial functions as well.

Moreover, the designs had never been licensed to a single manufacturer. The furniture had been produced by several carpentry workshops in Chandigarh and elsewhere, with instructions that the makers could improvise on the design or material as per their judgement and site requirement.

The designs and variants of these designs have been produced from the 1950s to the present day by numerous makers. It struck me that this was perhaps the first open-source design project of such scale, anywhere in the world.

I realised that we were not infringing on any particular maker or manufacturer’s rights either. We gave all of this good thought and only then decided to take the plunge.

Image courtesy: Phantom Hands Archive.

PR: That’s a big plunge to take given that so far, you only sourced and resold furniture. Now you would be manufacturing. Was that daunting?

DS: I didn’t know anything about manufacturing and next to nothing about furniture, so it could have been. The fact that it wasn’t was almost entirely because of my father-in-law, Sumanth Rao, who is also our technical advisor and ran his own furniture making firm for more than 35 years. He helped me understand the basics of the trade, how to source, how to select materials, etc. He also helped us recruit our carpenters and communicate our ideas to them.

We started with three models, two versions of the Chandigarh Office Chair (one X legged one V Legged) and the Easy Armchair.

Image courtesy: Phantom Hands Archive.

PR: You stuck to the original material - teak and cane. Did you depart at all from the original designs?

DS: The original furniture was made of local, economical material. Both teak and cane were that, then. Of course, teak is far from economical now. But yes, we stuck to the original materials.

We were clear that the furniture would be made by hand, using methods very similar to those used in the 1950s. Things like quality of glue, craftsmanship, and careful wood selection helped improve the robustness of the chairs compared to the vintage versions.

Most of the furniture had no definitive version. They were all hand-built by different carpenters, so almost every piece is a rendition of whatever the initial design was. We tried to take down the measurements and construction details of all the versions of the furniture we came across. Then we selected what we understood to be the most refined and ergonomically optimal version of a particular model, and stuck to it.

PR: Do you remember the first customer who bought Phantom Hands’ version of the Chandigarh Chairs?

DS: Yes, I do! He was a lawyer from Bangalore, where we are based, and knew a bit about the history of the chairs. When he came to buy, quite by chance, I mentioned that we had sourced the teak for the chairs from an old auditorium in Bishop Cotton Boys’ School, which had recently been brought down.

The wood was reclaimed from the beams and rafters and was more than 100 years old. Turned out that he was an alumnus of the school and immediately became sentimental about the purchase. So it seemed destined somehow.

I still remember that within a week I got a call from Rohan Murty, from the Infosys founding family. He had no idea about the background story of the Chandigarh Chairs, but had studied at Bishop Cotton School. He had heard that our chairs were made of wood reclaimed from the school. He too was keen on acquiring a pair.

The day the chairs arrived at his home he was being visited by a journalist from The Economic Times, who got very excited about the story and got in touch with us the next day. And that’s how our Chandigarh Chairs got their first press coverage.

Discovering Pierre Jeanneret: One of the Unsung Heroes of Chandigarh

A chance encounter with a pair of office chairs from Chandigarh sent Deepak Srinath looking into heritage furniture from the city, and architect-designer Pierre Jeanneret.

Read More

The Genesis of the Chandigarh Chair: Furniture as Infrastructure

There are several things unique about the furniture made for the city of Chandigarh in the 1950’s. The most striking among these is that they were conceived at the same time as the city, as a component of its master plan.

Read More

Upholding Europe’s Legacy: From Chandigarh’s City Furniture to ‘Pierre Jeanneret’s Chairs’

The quiet extraction of heritage furniture from Chandigarh spoke of the Indian government's disregard and neglect. But it also revealed a profit chain linking officials, antique dealers, and powerful Euro-American institutions.

Read More