Upholding Europe’s Legacy: From Chandigarh’s City Furniture to ‘Pierre Jeanneret’s Chairs’

Le Corbusier Centre, Chandigarh. Image courtesy: Wikicommons.

Parni Ray

09.10.2020

In 2004, Sotheby’s sold a lineup of furniture from the city of Chandigarh. They attributed them to the Swiss-French designer Pierre Jeanneret.

Three years later Christie’s, the other most powerful auction house in the world, presented a similar collection. Made exclusively for the city, a majority of the objects in these presentations were unknown outside of Chandigarh.

Quickly, they became a hit with trendsetters across Europe and America.

Chandigarh, in the meantime, woke up to its loss. The extraction of the heritage items from the city spoke of grave negligence on the part of the Indian government. But it also revealed a chain of profit that linked city administrators, European antique dealers, and some of the most powerful cultural institutions in Europe and North America.

Extracting From a Handmade City

Manmohan Nath Sharma, one of the first architects to join the Chandigarh Capitol project in 1950, passed away at his home in Chandigarh on October 30, 2016. He was 93.

Ar. Sharma had known the city since the early days of its conception. He worked with Mathew Nowicki and Albert Mayer on its first masterplan, and then later with Le Corbusier as his first assistant.

In 1965, shortly after Pierre Jeanneret retired from his position as Chandigarh’s chief architect, Sharma became the first Indian to be appointed to the post.

Given this deep-rooted relationship with the city, it is perhaps not surprising that Ar. Sharma devoted much of his life to Chandigarh’s preservation. In his final years, he led the Save Chandigarh Campaign, which urged the Indian government to protect the city’s public property from being removed illegally. [i]

His concern about the disappearance of Chandigarh’s material heritage had escalated following the auction of several pieces of the city’s furniture, architectural sketches, manhole covers, and other infrastructural paraphernalia, in Europe and North America.

The loss of these items – all property of the Indian government - would be irremediable, he pointed out.

‘This is a handmade city,’ he had told The Guardian in 2011, ‘It is unique. It can never be replaced.' [ii]

Crowning Glory of Modernism

The group of French vintage dealers who had extracted material from Chandigarh were more than aware of this distinction. Considered the crowning glory of Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, a pioneer of modern architecture and the International Style, Chandigarh is as much a hit with traders of vintage modernist items as it is with connoisseurs of modern design.

Objects associated with Le Corbusier never go out of style among the Euro-American high-art circles; even bric-à-bracs from Chandigarh offer excellent returns. The French dealers were, however, not after knick-knacks; they had their eyes on the city’s furniture.

Made in the '50s, along with the rest of the city, Chandigarh’s unique furniture had largely been confined to its public offices since their creation. [iii] Over time the dealers acquired several abandoned pieces of the furniture from scrap dealers, junkyards, and government auctions at knockdown prices. These were transferred to France, where they were refurbished and sold at auctions across Europe and North America.

Objects associated with Le Corbusier, pioneer of modern architecture and the International Style, never go out of style among the Euro-American high-art circles. Even bric-à-bracs from Chandigarh - arguably his crowning glory - offer excellent returns.

A Living Legacy

In a city full of Le Corbusier enthusiasts, the dealers’ pursuit of the furniture had invited no suspicion. Although some later claimed to have been hoodwinked by their posing as museum curators, others insinuate that several local agents were in on the sales and profited from them.

The exact details of the acquisition process are difficult to ascertain, but the law of the land would clearly not deem them illegal at the time. Since India’s export laws classify antiques as objects that are more than 100 years old, the transfer of large numbers of the city's furniture - all made less than 50 years ago - raised no alarm.

The auction houses swung into action immediately after.

In 2004, Sotheby’s New York presented five furniture lots from Chandigarh. At least one of them was priced at $26,400. Three years later, in 2007, Christie’s auctioned a cast iron manhole cover from the city for $21,600.

The year after, they put a pair of the iconic Chandigarh V-Chairs on sale with a reserve of $8,000 to $12,000. These hefty price tags immediately brought the furniture into the orbit of several power players in the global interior design market. A book on the furniture by the French dealers in 2010 helped fan further interest.

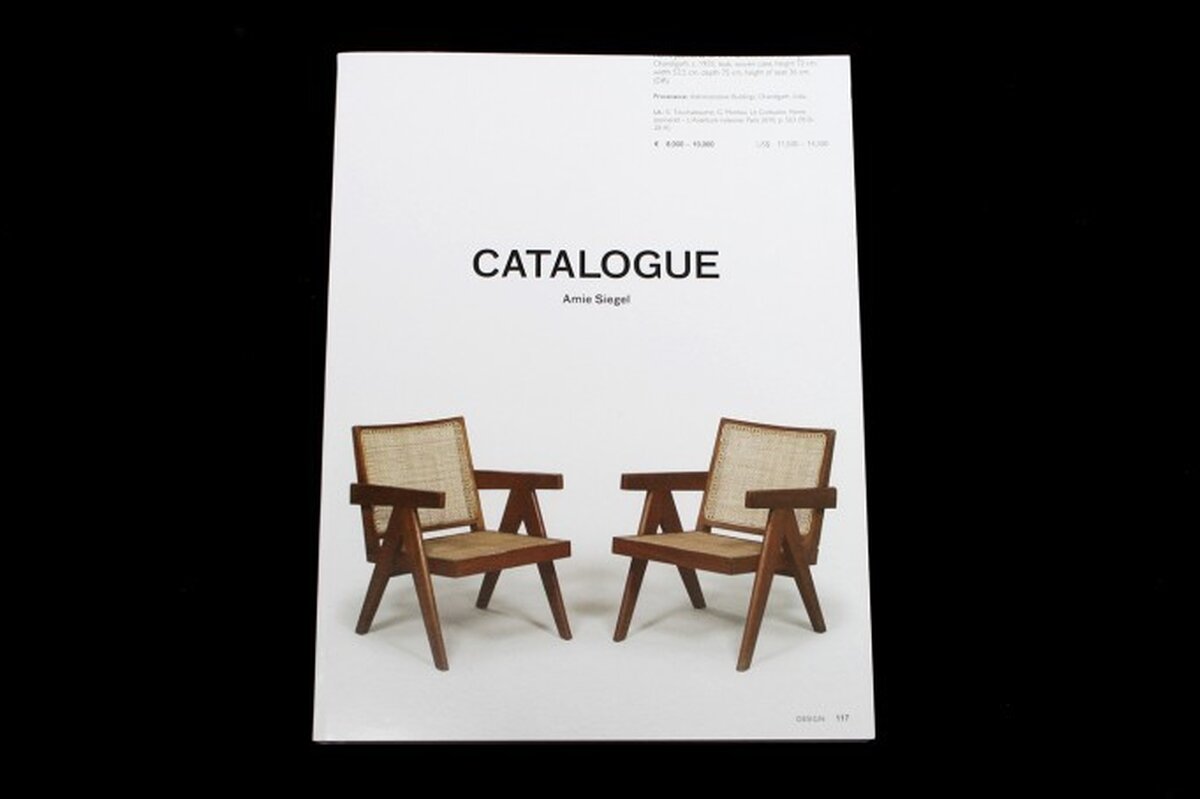

A successive publication by the artist, 'Catalogue' (seen here) published in 2014 is a chronological compilation of auction catalogues presenting the sales of Chandigarh furniture. The film itself was auctioned by Christie's in London, in 2013.

The Invention of the Jeanneret Chairs

The book established Pierre Jeanneret as a hitherto ignored modernist genius who had designed Chandigarh’s furniture single-handedly. A series of exhibitions built around the furniture hailed the chairs and desks as mid-century modernist masterpieces and displayed them in pristine white galleries like art objects.

All of this transformed the cheaply made, functional furniture into luxury products. In no time, Chandigarh Chairs became ‘Jeanneret Chairs’; the darling of celebrity interior stylists a success with publications, Hollywood A-listers, and a popular hashtag on Pinterest and Instagram.

Their increasing fame led several other vintage dealers to Chandigarh. Soon, the market was flooded with cheaply bought, refurbished chairs from the city. A stream of fake chairs emerged alongside. With no foundation policing their making or ascertaining provenance, counterfeiting proved an easy way to cash in on the chair’s tremendous fame and market price.

As sales soared, the news of the furniture’s stardom slowly trickled into Chandigarh.

It must have been then that Ar. Sharma discovered his city’s loss.

In no time, the Chandigarh Chairs became the ‘Jeanneret Chairs’; the darling of celebrity interior stylists, a success with publications, Hollywood A-listers, and a popular hashtag on Pinterest and Instagram.

Saving for Europe

As Queen Elizabeth’s crown could tell you, India is no stranger to the extraction of its cultural heritage. Bits, bobs, and even chunks of its material culture continue to reside in public institutions and private collections in Britain and elsewhere.

A number of these items, removed from their original locations before India’s independence, were taken on the pretext of the need to ‘save’ them.

British agents assumed the burden of protecting India’s heritage early into the imperialist regime. They decided what in India was ‘valuable,’ what could be bought and sold, what needed to be preserved, and what ought to be collected and placed in museums.

The British saw it as their duty to conserve India’s riches from the degeneration and decay they thought they witnessed in the region.

To this end, they shipped piles of valuable artifacts and objects to Britain for their ‘protection’. A good number of this material - never bought, simply taken - was placed in museums and private collections, where much of it continues to reside. [iv]

Rewriting the Narrative of Chandigarh

Although a good number of the Chandigarh furniture that was later auctioned was purchased in the city, the process involved in their acquisition is startlingly similar.

Like various other heritage materials previously removed from India, they too were labeled ‘valuable’ and declared in need of being saved by external agents. Their removal too was justified by the implicit suggestion that their local owners - the natives - had little understanding of the furniture’s value and therefore, needed European aid to appreciate and care for them.

Like with the treasures stolen by the British from India, the huge dividends earned from their sale benefited the furniture’s ‘saviours,’ not the people to whom they originally belonged.

As their popularity surged, the rags to riches story of the Chandigarh Chairs was repeated several times. Often, such retellings were accompanied by depictions of the furniture in various stages of dilapidation. These photographs, and/or written descriptions, evidenced the neglectful conditions that the dealers and auction houses hinted as the reason for the rescue of furniture from Chandigarh.

Like most images, however, these representations concealed more than they showed.

Image courtesy: artist/Simon Preston Gallery, New York.

Built for Prosaic Purposes

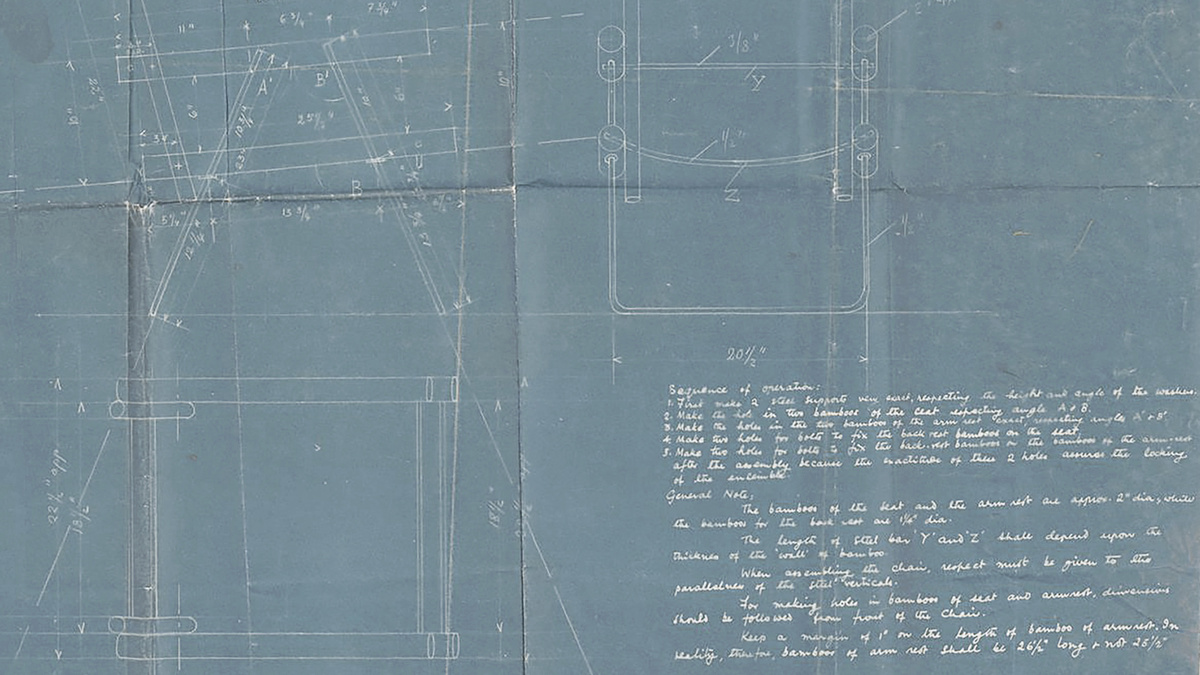

They failed, for instance, to let on that the furniture was mass-produced by local carpenters using easily available, low-cost materials. That the chairs had once been the modest outcome of a tight budget, meant to meet the demanding but prosaic needs of places of public service. There is no indication of these chairs being intended as art; just sturdy, functional city infrastructure, which, like all infrastructure, was expected to degenerate and be replaced over time.

Claiming Ownership

The images and the narrative built around them also fail to disclose that there is no conclusive evidence that the large variety of the city's furniture were all designed by Pierre Jeanneret. Many have pointed this out and raised objections to the sweeping attribution to the designer. [v] They bring up the contributions of other architects, local designers, and model makers, and propose author credits as an acknowledgement of their collective creative labour.

Jeanneret’s author function, however, plays a crucial role in the yarn spun around the furniture.

The images used to construct the narrative around the furniture concealed various details of their genesis. Most importantly, they failed to disclose that there is no conclusive evidence that the large variety of the city's furniture were all designed by Pierre Jeanneret.

The Story of the Underdog

Here was a Swiss-French designer connected to the upper echelons of European modernism, whose work had for years been eclipsed by the renown of his celebrated cousin, Le Corbusier. [vi] His genius had, however, shone forth in a foreign land; the furniture in Chandigarh was the obvious climax to his underdog story.

His masterful work, however, didn’t get the recognition it deserved and lay languishing amidst locals who had neither grasped the import of his modernist lineage nor the artistic value of his refined style.

It was this uncaring circumstance that had compelled the French dealers to intervene. Having retrieved the furniture from their inhospitable habitat, the dealers had brought the master’s work back among ‘his people,’ who would understand and revere it, and to ‘his place,’ where modernism and its fruits essentially belonged.

Image courtesy: Wikicommons.

A Familiar Narrative Oft Retold

This tale has many precursors. The narrative built around French designer Jean Prouvé’s Maison Tropicale, which was extracted from Congo-Brazaville in 2000, is among those contemporaneous with that of the Chandigarh furniture. The close parallel between their stories is highlighted by their frequent presentation together.

The Maison, an aluminium and steel flat-pack house, was conceived in the 1940s to provide housing in Congo, which was then a part of France’s violent colonial empire in Africa.

Only three prototypes of this colonial experiment had been made since it had proved both expensive and impractical. One of these was retrieved, from what Reuters describes as, ‘the steamy jungle and civil wars of the Republic of Congo’.

It had been found ‘dilapidated’ and bearing the scars of bullet wounds and neglect, but was quickly restored to health before being exhibited as a ‘modernist masterpiece’ at the UCLA, Yale University, Center Pompidou and Tate Modern. It was later sold for nearly $5 million by Christie's.

The extraction and eventual sale of both the Maison and the Chandigarh furniture was enabled by the natural claim white Europeans often assume over the work of other white Europeans in less powerful parts of the world.

‘Retrievals’ in such cases tend to take on a civilising tone, lending the ‘rescuers’ the zeal of moral crusaders, with no ethical understanding of the rights of others. [vii] This is especially true in the case of the furniture, which, if completely designed by Jeanneret, was created by its maker for the city of Chandigarh, as an employee of the Government of India.

Legally, therefore, all of it belongs to the Indian state.

The extraction and eventual sale of both the Maison Tropicale and the Chandigarh furniture was enabled by the natural claim white Europeans often assume over the work of other white Europeans in less powerful parts of the world. ‘Retrievals’ in such cases tend to take on an entitled, civilising tone.

Rethinking Design in the Present

Like Ar. Sharma and others advocated, the Indian government needs to take account of this and lay firm measures to protect its property. But this need was necessitated by the displacement and re-signification of this property by external parties. Without them, the furniture would be used and discarded by the people they had been meant for, as they had been thus far. This became disagreeable only because powerful Euro-American agents - among them people and institutions who were profiting from the sale of the furniture - deemed it so.

Historically, such agents have also played a crucial role in confining all making outside of the ‘West’ to the peripheries of design discourses. Often, such marginalization begins with the framing of objects in the manner the Chandigarh Chairs were, by associating them with European makers while invisibilising non-European labour.

This practice borrows from colonialism but is alive and well in the hands of several design-driven enterprises of our times.

To change this would mean to reorient our present by reconfiguring our ongoing relationship with the past. As far as design history is concerned, this ought also to change our view of past objects, regard natural processes of deterioration and decay with as much reverence as we do conservation.

Instead of lamenting about ‘woeful neglect’ as a threat to design history, this would mean accepting that the woeful neglect is, perhaps, part of the history of design.

Endnotes:

[i] These efforts have eventually proved successful. In 2017 the sale of Chandigarh’s city furniture was made illegal. In 2020 the Archaeological Survey of India directed the Commissioner of Customs, All Customs Exit Channel (air and seaports) to prohibit the export of heritage furniture from Chandigarh. In 2016 Chandigarh’s Capitol Complex, designed by Le Corbusier, was also declared a UNESCO World Heritage site, as MN Sharma had wanted.

[ii] In his interview with Phantom Hands, Vikramaditya Prakash made similar assertions.

[iii] It is likely that the furniture migrated within India. Its appearance in Madan Mahatta’s photographs (link to essay on Madan Mahatta’s photographs) of IIT Delhi proves that they – or their design- definitely travelled. Whether they travelled abroad is unclear. Neither of these journeys, however, appears to have been chronicled.

[iv] See Ishani Ghorai and Samayita Banerjee, Antiquities Theft and Illicit Antiquities Trade in India, October 2018, Sahapedia

[v] The most comprehensive discussion about this carried forth by Nia Thandapani, Petra Seitz and Gregor Wittrick in their presentation, Chandigarh Chairs: Missing Histories, held on the 24th September, 2020, hosted by Bangalore International Centre. Accessible here.

[vi] Pierre Jeanneret was Le Corbusier’s cousin, Corbusier’s real name of course was Charles-Édouard Jeanneret. Jeanneret had worked with Corbusier for years. The narrative built around Jeanneret frequently suggested that he was the more ‘overshadowed architect of the pair’.

[vii] This is coupled with an emotional charge associated with repatriation. On spotting the Maison Tropical in Brazaville, for instance, the French dealer who finally ‘retrieved’ it described feeling ‘Big emotion, great emotion’.

In Conversation With Professor Vikramaditya Prakash: On the Authors of Chandigarh

Dr. Vikramaditya Prakash is Professor of Architecture at the University of Washington, Seattle and grew up in Chandigarh. Here he discusses the first generation of Indian Modernists who worked on the architecture & furniture of Chandigarh.

Read More

The Genesis of the Chandigarh Chair: Furniture as Infrastructure

There are several things unique about the furniture made for the city of Chandigarh in the 1950’s. The most striking among these is that they were conceived at the same time as the city, as a component of its master plan.

Read More

In Conversation With Ar. Shivdatt Sharma: On the Chandigarh School of Modernism

Architect Shivdatt Sharma is one of the premiere modernist architects of India. He started out in the Chandigarh Capital Project Team under the leadership of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret.

Read More