In Conversation With Ar. Shivdatt Sharma: On the Chandigarh School of Modernism

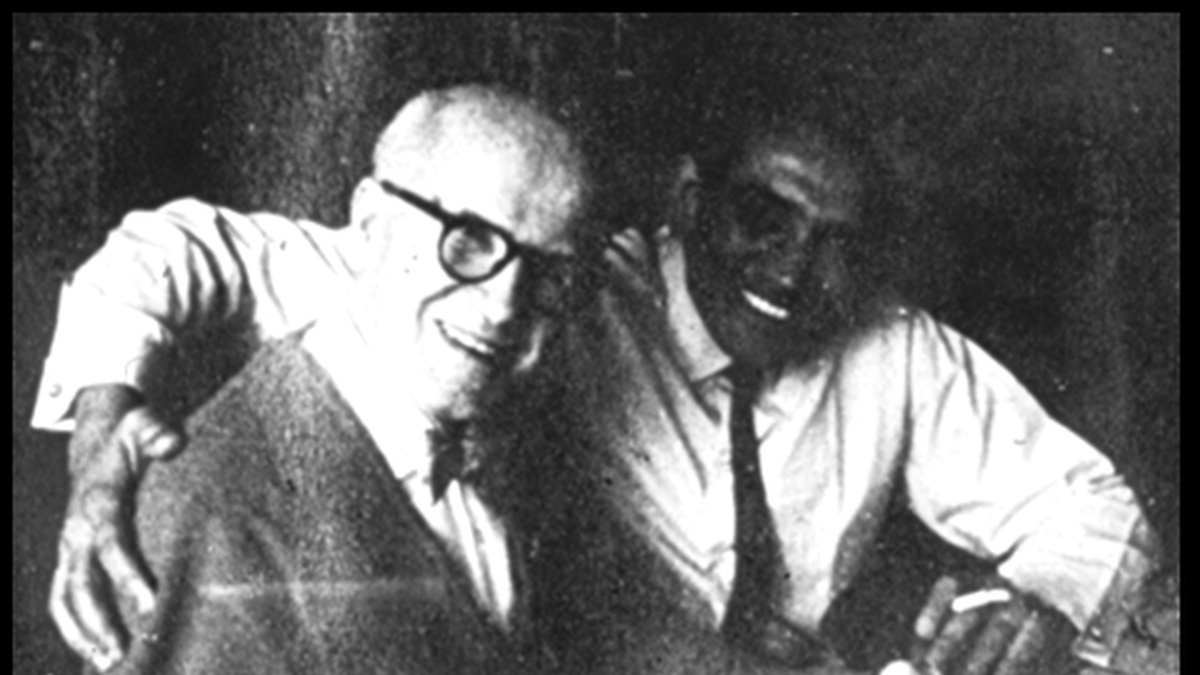

Architect Shivdatt Sharma with Pierre Jeanneret at dinner in Geneva, shortly before the latter’s death in 1967. Image courtesy: Shivdatt Sharma.

Parni Ray and Deepak Srinath

04.09.2020

Premier Modernist Architect

Architect Shivdatt Sharma started out as an architect in the Chandigarh Capital Project Team under the leadership of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret. Later, he was the Chief Architect of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), Bangalore, for nearly a decade.

During this time, he was also selected to design two sectors in Abuja, the new capital of Nigeria, then to be designed by the modernist Kenzo Tange. When the project was abandoned due to a coup in the country, Sharma returned to Chandigarh to start his private practice, which he still continues to maintain.

Distinctive Style

Over the course of his prolific career, spanning a little more than half a century, architect Shivdatt Sharma has established himself as one of the most eminent modernist architects of the country.

His distinctive style is stamped across the premises of several institutions of national import, including the Vikram Sarabhai Hall, Ahmedabad, Satish Dhawan Space Centre Master Control Facility, Sriharikota, and the Central Scientific Instruments Organization, Chandigarh.

Shrugging away its assumed belatedness, Shivdatt has persisted in his endeavour to hold on to the ideals of modernism, lending it contemporaneity even in the face of the rapidly changing character of the built environment in India.

Read on for excerpts from his animated account of his time at the Chandigarh Capital Project Office and his mentor, Pierre Jeanneret.

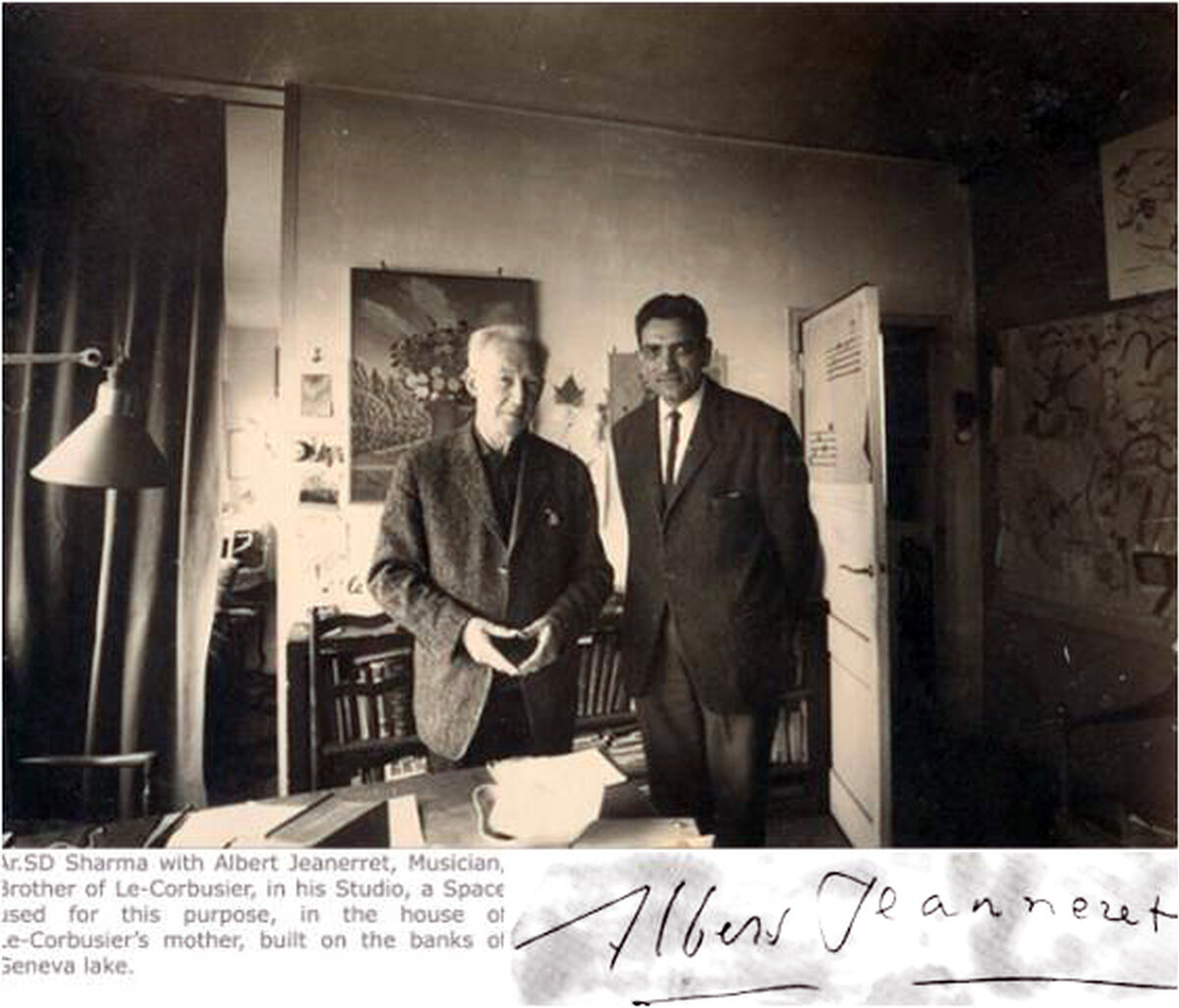

Image courtesy: Shivdatt Sharma.

About becoming a part of the team for Le Corbusier’s Capital Project of Chandigarh.

I was born in a middle-class family…it was me, my parents and three brothers… we lived in Montgomery, which became a part of Pakistan after partition. When it (the partition of India) was announced we were in Sialkot, visiting our relatives. We heard the news on the radio and ran, without taking any clothes or money.

I was 16 when I ended up in a refugee camp in Amritsar and took up work as a labourer. I had to work hard to finish my diploma; I was not yet 18. We had no money so I took up service. After a few years, I heard that the Chandigarh administration was recruiting architects. So I applied and got the job (laughs). That is how I became a part of the Capital Project Team in 1954.

By the late '60s, there were no new projects in Chandigarh, only some smaller buildings or additions here and there. I was not happy with the sluggish pace of work and wanted to take up something more challenging, which is why I then took up a position at ISRO.

On the Chandigarh design office under Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret.

When Le Corbusier and Jeanneret came to India there were only two U.S.-trained Indian architects designing modern buildings in the country. But Le Corbusier was, of course, the high-priest of modernism himself, so his influence on Indian architects was major.

The Chandigarh Capitol Project office was like a school of architecture. If you think about it the reason for this is obvious, Chandigarh is one of the only cities in the world to be designed by an architect. This is significant because it isn’t usual. But Le Corbusier didn’t make any difference between town planning and architecture.

Image caption: Wikicommons.

Not a strictly top-down hierarchy.

There were many hierarchies at play during the making of Chandigarh. There was friction between (Jawahar Lal) Nehru’s vision and the rural constituencies, between the architect’s office and the administration. The architects were to report to the chief engineer, P.L Verma. Because Le Corbusier mostly didn’t bother with such bureaucracy, it was Jeanneret who negotiated with them, and I would say he did so very well.

It was mainly due to him that the structure of the Capital project office was not strictly top-down. It had a strong culture of promoting juniors to work on projects independently. Talent, perseverance, and dedication were rewarded.

The best prize obviously was to work directly with Le Corbusier (laughs). Jeanneret ensured that almost everyone at the office had the opportunity to work with Le Corbusier. My time came in 1963 when he asked me to work with him on the Government Museum and Art Gallery.

Le Corbusier spent a lot of time discussing basics; if you build a wall you have to put an opening, a window there. And you should know where to put that window. He was very thorough with the mathematics of it at all. Even the rough sketches he did were full of detailed descriptions supported by mathematical calculations. Being mathematically accurate, precise, that was the most important thing for him.

Image courtesy: Shivdatt Sharma.

I picked this up from him and for that I consider myself very, very lucky. I can safely say that what I learnt at the Capital Project office impacted me deeply and affected the rest of my professional career. The lessons about designing for the climate, using local, readily available materials stayed with me. I took these learnings with me wherever I went, including the 10 years I spent at ISRO in Bangalore.

For me the signature ideas remained the same, only the external conditions changed and needed to be adapted to. They often ask me how long the modernist style will last and I always say that anything rational and logical is forever.

On his experience working with Pierre Jeanneret.

Like many of the other architects at Chandigarh, I developed a close relationship with Pierre Jeanneret, I would even say he was my personal and professional mentor.

Working with him was different from working with Le Corbusier, who wanted everybody to know him through his books and writings before he interacted with them. He did not have a lot of patience, but you could learn a lot observing him.

Image courtesy: Wikicommons.

Jeanneret, on the other hand, had a lot of patience. He spoke at length about the work at hand and taught without making any effort. He made us these do's and don'ts charts, which were very helpful; they clearly outlined what we architects ought to do and what we should avoid.

He and I worked closely for a year and a half on Nayantara and Gautam Sehgal’s residence in Chandigarh. This was a private project so we worked on it after hours, at Jeanneret’s house. It allowed me to learn his design ideology up close and was a wonderful experience - undoubtedly one of the most valuable ones of my life!

Jeanneret and the making of Chandigarh's furniture.

Jeanneret, of course, designed furniture before he came to Chandigarh. But I think his achievements in this regard peaked here.

There were no specialists involved in the making of the furniture, they were built completely by local craftspeople. Jeanneret was also quite the craftsperson himself. He made all kinds of things with his own hands - paddle boats and row boats for example that he used to go boating in Lake Sukhna. He experimented with many materials, bamboo, teak and others, while working on the furniture. The joints he designed were very detailed, with no nails or screws. They reflected Jeanneret’s nature, he was quite meticulous.

On his upcoming book on Pierre Jeanneret.

I have been working on my book on Jeanneret for three years. Every few years I find some new information about him and make additions. Recently, I found something new again, so that took some time to add (laughs). But now we are ready with the book, let’s see when we get to publish it.

In Conversation With Professor Vikramaditya Prakash: On the Authors of Chandigarh

Dr. Vikramaditya Prakash is Professor of Architecture at the University of Washington, Seattle and grew up in Chandigarh. Here he discusses the first generation of Indian Modernists who worked on the architecture & furniture of Chandigarh.

Read More

Discovering Pierre Jeanneret: One of the Unsung Heroes of Chandigarh

A chance encounter with a pair of office chairs from Chandigarh sent Deepak Srinath looking into heritage furniture from the city, and architect-designer Pierre Jeanneret.

Read More

A Visit to the Chandigarh Architecture Museum

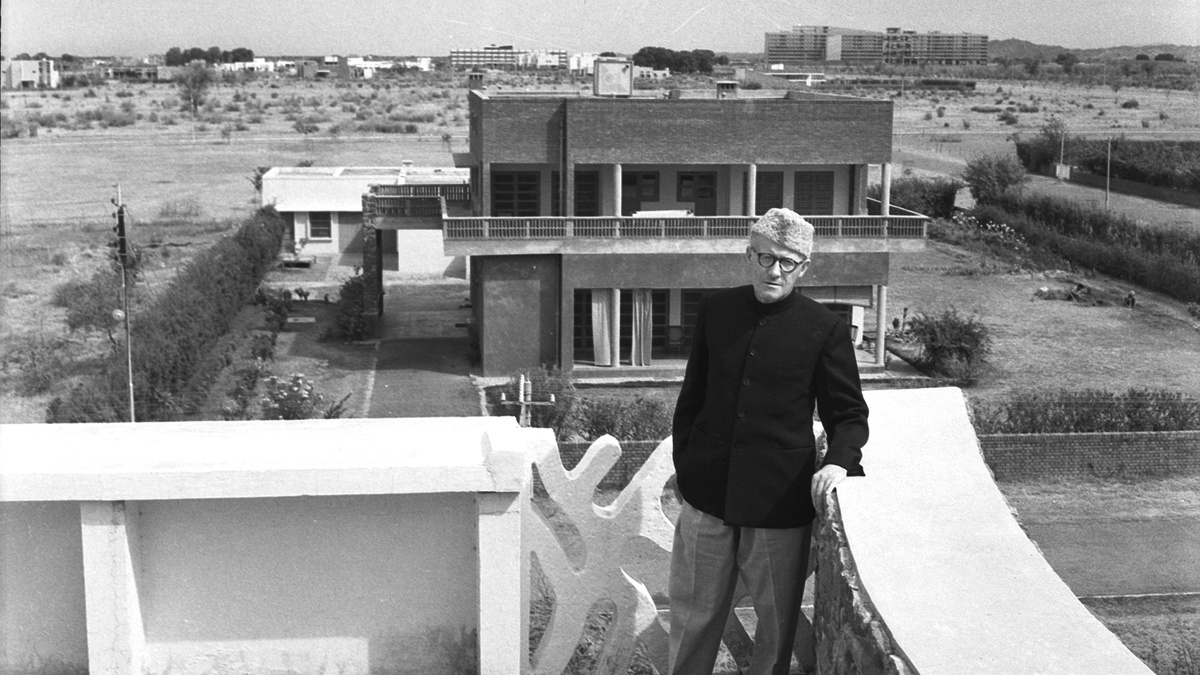

The Chandigarh Architecture Museum is one of my favourite buildings in Chandigarh. Designed by architect S.D. Sharma, a protege of Corbusier and Jeanneret, the building draws inspiration from the Pavillion Le Corbusier in Zurich.

Read More