In Conversation With Professor Vikramaditya Prakash: On the Authors of Chandigarh

Professor Vikramaditya Prakash.

Parni Ray and Deepak Srinath

25.09.2020

Dr. Vikramaditya Prakash is Professor of Architecture at the University of Washington, Seattle. His research focuses on modernism, postcoloniality, global history, and architecture.

Among the many publications to his credit are ‘The Struggle for Modernity in Postcolonial India,’ ‘A Global History of Architecture,’ ‘Colonial Modernities,’ and ‘Chandigarh’s Le Corbusier’.

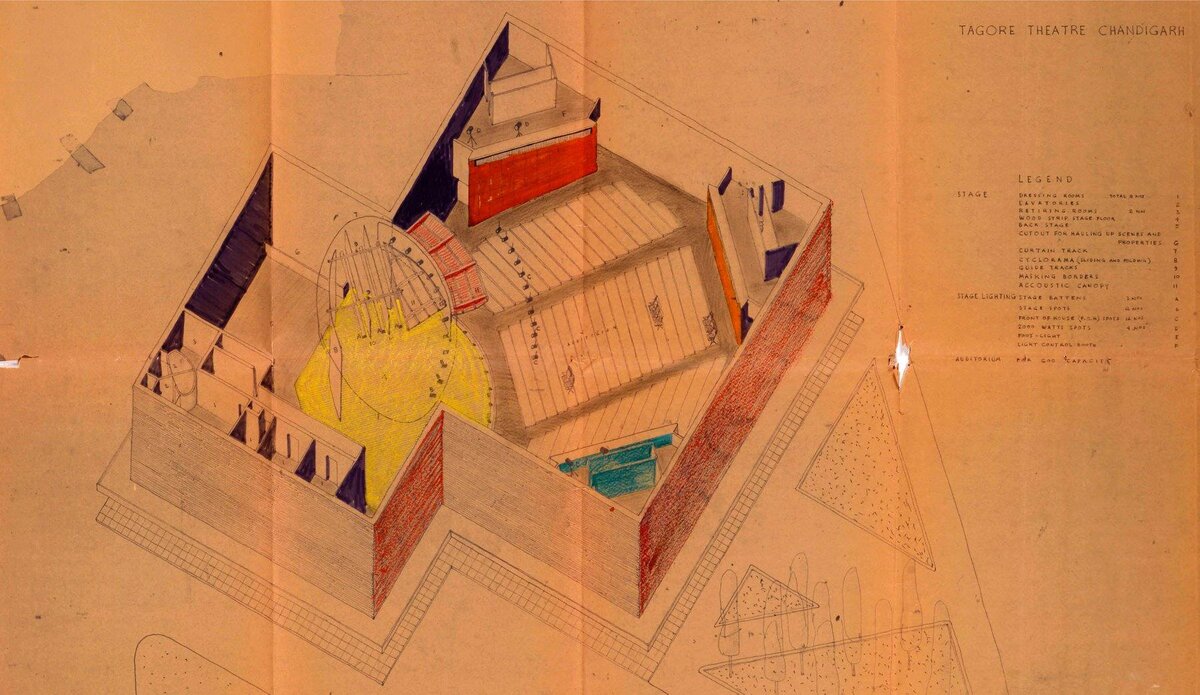

His recently published book, 'One Continuous Line: Art, Architecture and Urbanism of Aditya Prakash’, is a monograph exploring the life, work and art of his father, among the first generation of Indian Modernists who worked on the Chandigarh Capital Project under Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Jane Drew, and Maxwell Fry.

Deepak Srinath (DS): What was it like growing up in Chandigarh? Were you aware of the significance of the architecture and furniture you were surrounded by?

Vikramaditya Prakash (VP): It won’t be an exaggeration to say that I grew up with a deeply internalized appreciation for and curiosity about the architecture in Chandigarh. It definitely functioned as a foundation to my interest in my field.

As for the furniture, you know, they were really just an ordinary fact of life. They were just ubiquitous and functional; we didn’t think actively about them. It is only now when modernism is back in favour in Western high-art circles and when the story of the making of the so-called ‘Jeanneret furniture’ is being retold and celebrated that they have assumed an outsized prominence, and become almost a short-hand for the Chandigarh project.

For us this wasn’t Jeanneret’s furniture, it was the Chandigarh ‘governmental’ furniture, designed by many, many people, the whole team. My father (Aditya Prakash) too, for instance, designed furniture. They were a daily part of my life, they still are. I did and still do a lot of my reading sitting in one of my favourite chairs by him…while, incidentally, a lot of other people in Chandigarh tend to think of them as being very uncomfortable!

DS: Tell us about your father. Apart from being an architect, he was an artist, a theatre actor, and also designed furniture. Quite reminiscent of Le Corbusier...

VP: Well, yes, you could say that my father had a typical early 20th c. Enlightenment approach to all the arts; he saw them all as connected and not distinct aesthetic disciplines.

Indeed, I would say that my father wanted to be an artist first, innately. But what happened was, early on in his life, his desire to be an artist was suppressed by the pressures of colonial education, which was inherently partial to subjects such as medicine and engineering, and by the pressures of being an Indian male who was expected to learn a ‘proper’ profession. That's why he became an architect; which was understood, of course, as a sub-discipline of engineering, a haloed and very salary-able profession in colonial India, and even today.

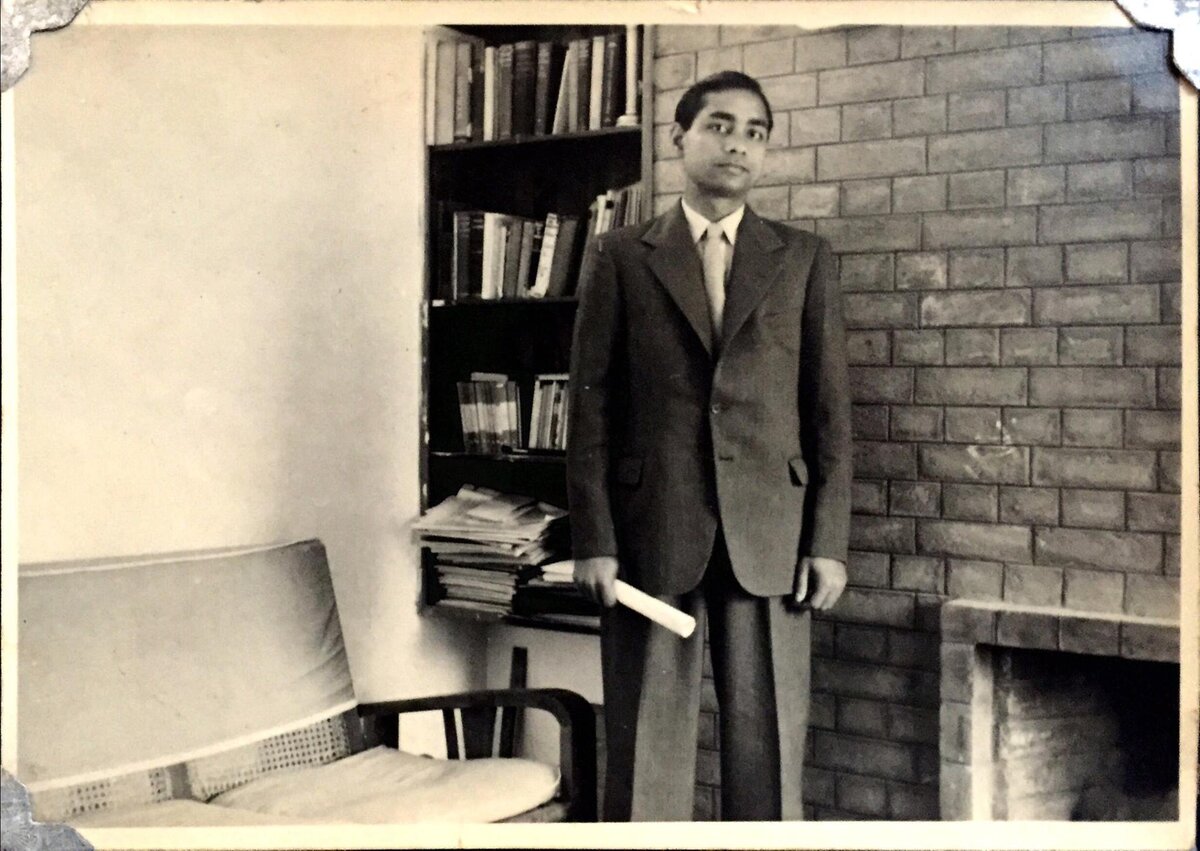

Image courtesy: Vikramaditya Prakash.

I think he inculcated a deeply internalized schism between his artist self and his professional self and this came particularly to the fore when he went to the UK in 1947. He was there to work and study but spent his evenings and weekends immersed in the arts - watching theatre, going to concerts, frequenting galleries – all of which were free!

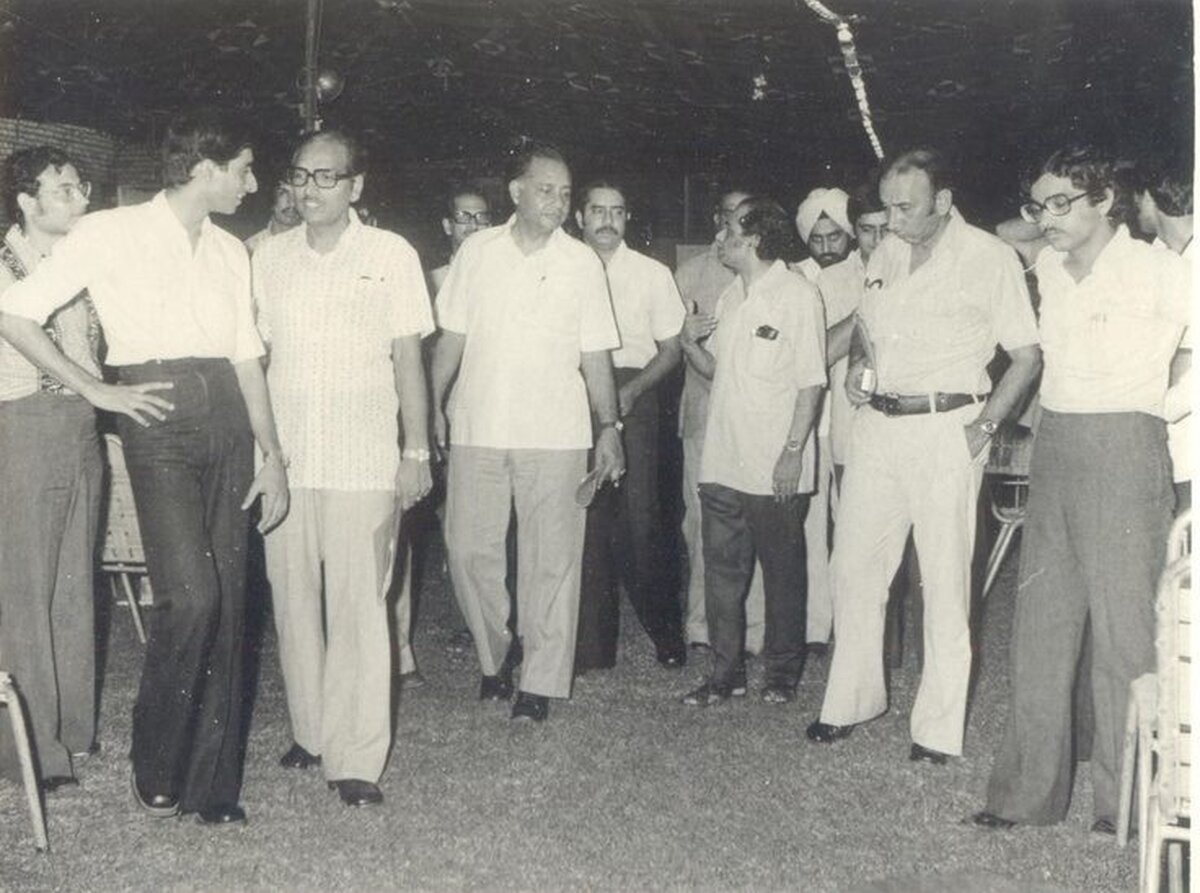

Ultimately this split, this schism, which he never repressed but actively explored, proved to be an asset in his work as an architect for Chandigarh, I think.

In many ways you could say that Le Corbusier set the tone for the work culture there. Corb, as is well known, used to paint in the morning and then come into the office only in the afternoon. There was no difference between architecture, urban planning and landscape, or for that matter philosophy and sociology for Le Corbusier (laughs)…I think my father felt like that was a model he could follow.

My father’s diverse interests were a result of a series of accidents, rather than a cultivated intellectual position, like that of most European modernists - Vikram Prakash.

Parni Ray (PR): Speaking of your father’s interest in the arts, he was also a photographer...

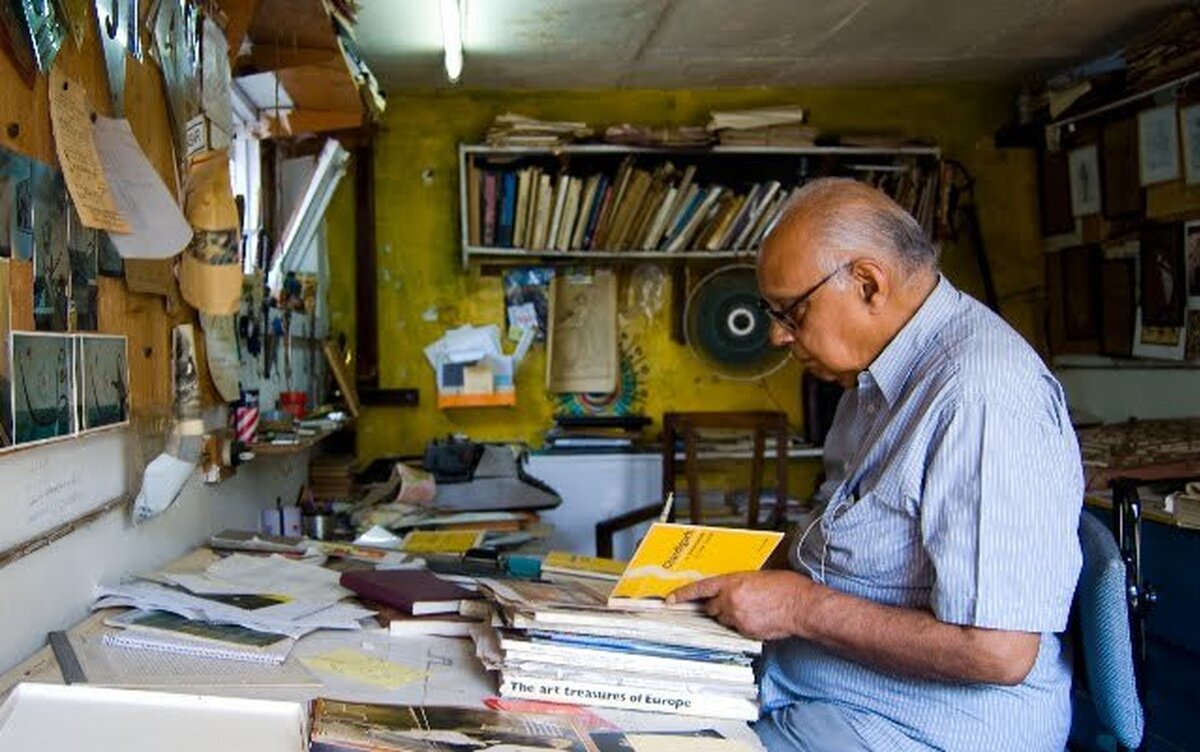

VP: Yes. In fact a whole chapter of my upcoming book on him dwells on this. The short story is that he got interested in photography due to Jeanneret, who was of course Le Corbusier’s photographer (who was terrible with the camera). He went around with a camera slung around his neck and took all the photographs of work being done on the Capitol Complex. I think that was definitely an influence for my father.

Then we moved to Ludhiana in the early 60s and he was designing various agricultural engineering campuses there. At this time he was surrounded by Canadian and American scientists and agricultural engineers and he managed to acquire a couple of secondhand cameras from them.

Owning a camera at that point in India was quite something. It was an expensive hobby, but he was clearly into it. He loved slides and setting up his projector during the evenings to show us the photos he had taken. We were of course only interested in pictures we ourselves were in (laughs).

PR: Are these photos among the Aditya Prakash archives now at CCA?

VP: Yes. The archive has about 2000 architectural drawings, photo negatives, all my father’s equipment, his journals, writing pads…everything I had, besides his art. The archive is still being digitized, but parts of it are available online. CCA often digitizes things on demand.

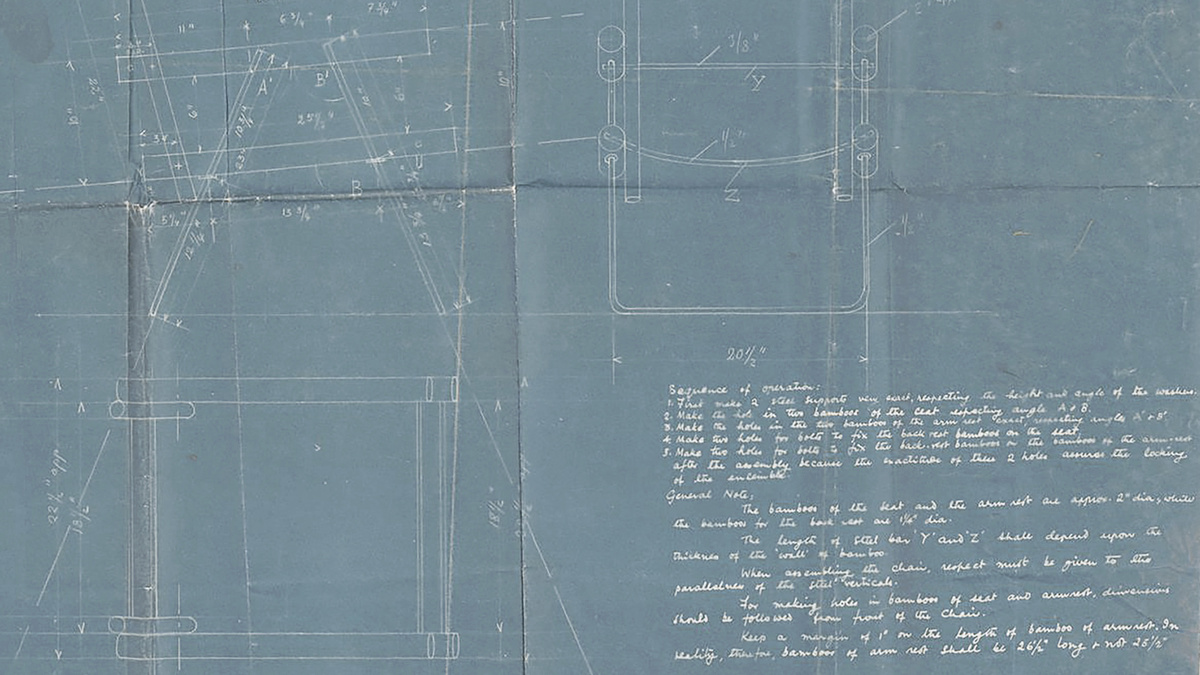

Image courtesy: Vikramaditya Prakash.

DS: I read somewhere that your father spent some time at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA). Would you say this influenced his later work in any way?

VP: Oh, very much so! I would say his time in Glasgow was foundational. He went to London in 1947 and began attending evening classes at what is now the Bartlett School of Architecture (London Polytechnic then). Then, after becoming an ARIBA (Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects), he moved to Glasgow to work.

He hated his job in Glasgow (laughs). He was surrounded by post-war trade architects and not being of the same sensibility he constantly butted heads with them and, I suspect, faced considerable racial hostility. It was, I think, to escape from all of this that he started taking classes at the GSA.

I have some photographs of his work from his time there, of tiny clay sculptures, etc., which resonate with his later artistic work. And when you look at these you clearly see that the seeds of his fondness for and understanding of modernist aesthetics had been planted during his time at the school. He was there when he got the offer to join the Chandigarh Capital Project Team. He joined immediately after, in 1952.

Image courtesy: Vikramaditya Prakash.

PR: Chandigarh has been central to much of your academic work. In your writing about it you often touch upon the theme of authorship that has come to underscore the city’s story - how Chandigarh, for instance, is seen as ‘Le Corbusier’s’ and the furniture from the city is understood to be ‘Jeanneret’s’…

VP: There is always a fetishisation of the author’s hand in design - be it furniture or architecture - even though we all know that making doesn’t quite happen in the univocal way this suggests. The fixation with the designer comes from the 19th C. approach of art connoisseurship, which relied on identifying a work of art in terms of who made it.

In the context of Chandigarh, this fidelity to authorship conflates with colonialism and its built-in hierarchies and biases. One of the most defining features of colonialism is the notion that the spirit of originality and internal genius resides in the white masters, and those colonised can only copy. Hence, there is little acknowledgement of the fact that everyone on Jeanneret’s design team and the craftspersons who built them, had a role to play in the designing and making of the furniture for the city, other than as copyists or draftspersons.

PR: You have often pointed out that the authorship of Chandigarh furniture lies as much with the craftspeople as it does with the designers...

VP: Yes! I mean consider why the furniture was made in the first place. The new buildings in the new city had to be furnished. Budget was slim and buying new furniture off a catalogue was going to be far more expensive than making it locally, with local materials, using the skills that were readily available. This is how the chairs and the rest of the furniture came to be designed as it was. It was cheap, functional stuff. None of it was intended as high art.

We have heard so many anecdotes of carpenters being instructed to make a lot of furniture just by verbal directions, without any drawings or anything and them just nodding along and saying ‘haan, ho jayega’ (Hindi words, trans. yes, it'll be done) (laughs).

PR: Like carpenters in India usually do...

VP: Exactly! And what happens after that? Putting the final piece together required individual thinking by the craftsperson, using available material innovatively, making alterations to the initial plan whenever necessary.

The craftspersons worked with one eye on the designs and expectations of the architects, and the other on craft. This is nothing new, but we denigrate the latter. If that isn’t co-authoring, then what is?

The furniture in Chandigarh was made with the design thinking methodology of jugaad. Like the built environment of the city, its modernism was handmade and hand-poured. This is true of all kinds of architecture and making in India even today; they are defined by the clear marks of the human labour that has gone into them - Vikram Prakash.

I do think the authorship of the Chandigarh furniture lies as much with the craftspeople as it does with the designers, and as much with the Indian team as with the white masters.

This is what I have elsewhere argued as the DNA of global modernism or diffractive modernism. Several people all over the world are now remaking the furniture, but local Indian handcraft is in its DNA. To ‘preserve’ the design, this mode of making - which particularized it - needs to be kept alive.

Image courtesy: Vikramaditya Prakash.

PR: In a recent Dezeen article you mention that unlike the Capitol complex, a lot of other structures in the city, created alongside the Capitol by local architects at the same time, are not even in the UNESCO dossier and will probably be broken down. So, while there is a lot of attention around the conservation of history and heritage, it is curious how a certain kind of past is seen as worthy of being conserved and not another.

VP: Historical preservation is often a colonial project aimed at saving the white master’s genius creation from the colonised, who, being ‘inferior,’ are thought to have failed to grasp its value. That is certainly the case here.

PR: In many ways we, as postcolonial subjects, have internalised this narrative too, wouldn’t you say? Let me explain what I mean. What we describe as India’s peak modernist moment in the 50s is marked by transnationalism. Design wise it is defined by Pierre Jeanneret, Le Corbusier, Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew’s work in Chandigarh. In Delhi Achyut Kanvinde and Habib Rahman, who trained under Walter Gropius and brought back elements of the Bauhaus ideology, begin to gain prominence. Alongside, National Institute of Design was being conceived too and Ray and Charles Eames were invited to formulate what became the Eames Report.

Because we understand all of this to have shaped Indian modernist design, we are also constantly working with the idea that we were ‘taught’ modernism by agents of the West. How to exorcise ourselves from this notion of a derived modernism, learnt from Euro-Americans?

VP: We have indeed internalised this narrative. The babus bought into the fiction of white colonial superiority during the British regimes and we in India continue to believe in it even today. This is the classic master-slave dialectic - the struggle between your empowered, free self and the bonded self - that everyone from feminists to queer theorists and of course, post colonialists, talk about. Even Nehru talked about the ‘backwardness’ of India and how that had brought about our colonial enslavement…today our obsession with becoming ‘world-class’ betrays our continuing internalisation of this ‘backwardness’ narrative.

Elsewhere, I have suggested that a way around this, at least as far as modernism is concerned, would involve abandoning the idea that modernism belongs to the West. Until we let go of the idea that modernism is Western, it will always be something the rest of the world has derived or emulated. Instead of understanding it as a singular (European) creation authored by a singular (European) history, I have suggested that modernism be understood as a global heritage.

Historical preservation is often a colonial project aimed at saving the white master’s genius creation from the colonised, who, being ‘inferior,’ are thought to have failed to grasp its value. That is certainly the case here - Vikram Prakash.

Image courtesy: Vikramaditya Prakash.

An easy way to understand such a trans-local or global, diffractive modernism is to imagine 20 stones being flung into a pond at the same time. What I am suggesting is that where the stones fall is not where the event occurs; instead, the event is the waves, and the waves crossing and diffracting each other. (This derives from ideas that have been formulated by Karen Barad, a particle physicist who is also a queer-feminist theorist.)

Such an approach would make room for various kinds of modernists, including Indian modernists to be included within the story of modernism, without having to argue their legitimacy as an ‘original’. This would obviously require a tremendous reconfiguration of our overall cultural approach to evaluating works of art in terms of masters and derivatives.

And this is not just an art thing - this is cultural and political. Eurocentrism is still a major problem in the world. The upheavals we are witnessing at the moment in America and across the world are, in fact, demanding exactly such dramatic cultural reconfigurations.

Perhaps, when the climate crisis finally brings us all to our knees, is when they will finally begin to pan out.

Image courtesy: Vikramaditya Prakash

See: One Continuous Line, an exploration of the life, work and art of Aditya Prakash.

Visit: Chandigarh Urban Lab, a project on the modernist city in the age of globalization.

Buy: Vikramaditya Prakash’s books on Chandigarh.

In Conversation With Ar. Shivdatt Sharma: On the Chandigarh School of Modernism

Architect Shivdatt Sharma is one of the premiere modernist architects of India. He started out in the Chandigarh Capital Project Team under the leadership of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret.

Read More

Upholding Europe’s Legacy: From Chandigarh’s City Furniture to ‘Pierre Jeanneret’s Chairs’

The quiet extraction of heritage furniture from Chandigarh spoke of the Indian government's disregard and neglect. But it also revealed a profit chain linking officials, antique dealers, and powerful Euro-American institutions.

Read More

The Genesis of the Chandigarh Chair: Furniture as Infrastructure

There are several things unique about the furniture made for the city of Chandigarh in the 1950’s. The most striking among these is that they were conceived at the same time as the city, as a component of its master plan.

Read More