The Genesis of the Chandigarh Chair: Furniture as Infrastructure

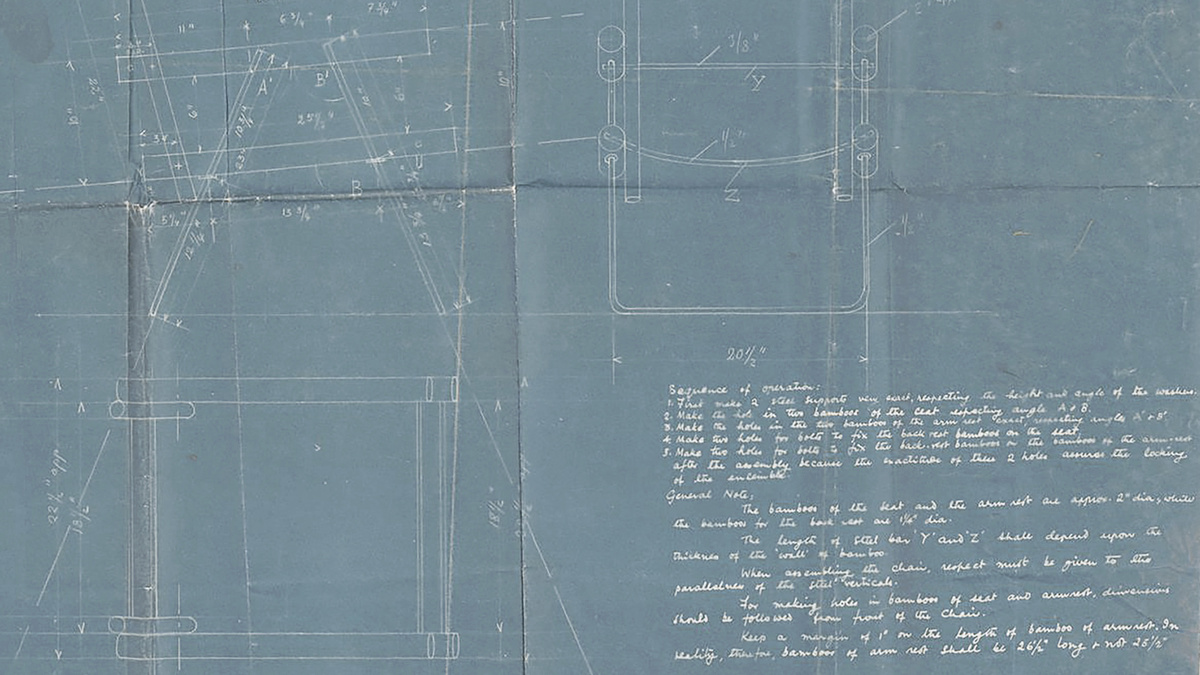

Elevations and plan for a bamboo armchair, between 1951-1965. Image courtesy: Pierre Jeanneret Fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal; Gift of Jacqueline Jeanneret.

Parni Ray

11.09.2020

Distinct Genesis

There are several things unique about the furniture made for the city of Chandigarh in the 1950s. The most striking among these is that they were conceived at the same time as the city, as a component of its master plan.

The coincidence of the furniture’s making with the birthing of the city it is associated with, makes it quite exceptional. It sets it apart, for instance, from other furniture design - Scandinavian, Japanese, Brazilian - which are similarly linked to specific places.

Unlike them (this distinction highlights), the furniture in Chandigarh was not meant to be defined by the place it was related to. Rather, it was to help define the city as a place by offering it coherence and its citizens a common amenity, in much the same way as infrastructure does.

Bureaucratic Aesthetic

Little regarding its furniture appears in the volumes written about Chandigarh – the first planned city of independent India designed by a team of local and international architects led by Le Corbusier.

Even Chandigarh residents spared it little thought. To them the city furniture was - continues to be remain - not only prosaic and ubiquitous but also stodgily bureaucratic, related as they have been to public offices from the start. [i]

Considerable conversation, however, followed the ‘discovery’ and ‘rescue’ of the furniture by a couple of French gallerists in the late 90s. Much of this focused on Le Corbusier’s cousin, Swiss-French architect Pierre Jeanneret.

Lauding him as an underdog modernist genius who designed the furniture, hundreds of abandoned chairs from the city (bought as scrap) started being sold as vintage luxury items across Europe and North America.

Image courtesy: Phantom Hands Archive.

A Star is Born

In no time the distinctive chairs from Chandigarh became the ‘Jeanneret Chairs’ - a star in the international interior design scene.

Everyone from designer Axel Vervoordt and architect Joseph Dirand to TV stars Kim and Kourtney Kardashian and Ellen Pompeo made room for them in their homes. But the wave didn’t end there.

Soon a variety of other furniture and objects from the city, including manhole covers, were being sold under Jeanneret’s name by some of the biggest auction houses in the world.

This sudden clamour around it - and its (apparent) author - all but drowned the patchy origin story of the furniture. Even a brief attempt to piece this past together, however, makes the intricate relationship between the furniture and the making of Chandigarh apparent.

Little regarding its furniture appears in the volumes written about Chandigarh – the first planned city of independent India. Conversation, however, followed the ‘discovery’ and ‘rescue’ of the furniture by a couple of French gallerists in the late '90s.

A City of the Future

The city of Chandigarh was deemed necessary for a variety of reasons. The recent partition of India and Pakistan (a parting gift of the 200 years of British rule) had left Lahore, the chief administrative and cultural centre of the Punjab province, on the Pakistan side of the newly drawn border.

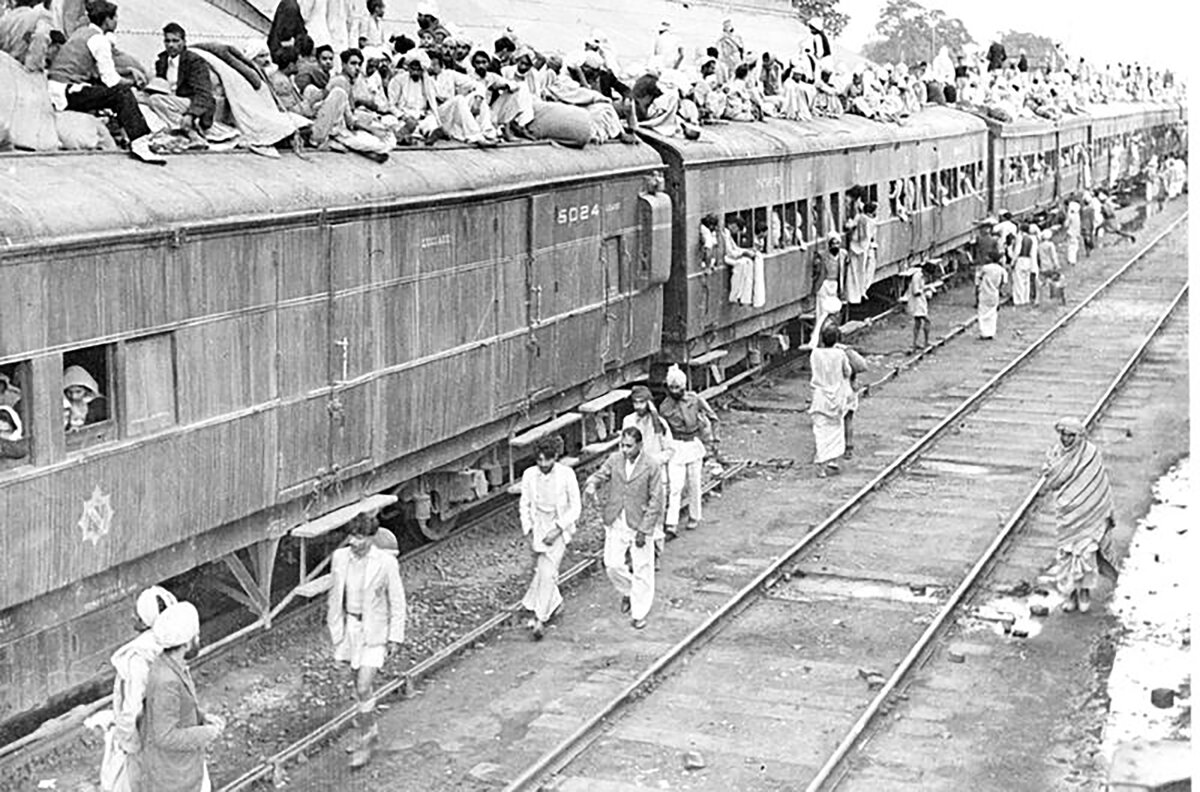

The partition had also induced an exodus from both sides. More than 10 million people had been forced to leave their homes and flee to the either country based on their religious identity.

Several hundred thousand people died in the communal violence that had broken out as a result of this upheaval.

Image courtesy: Photo Division, Government of India.

Embodiment of Modernity

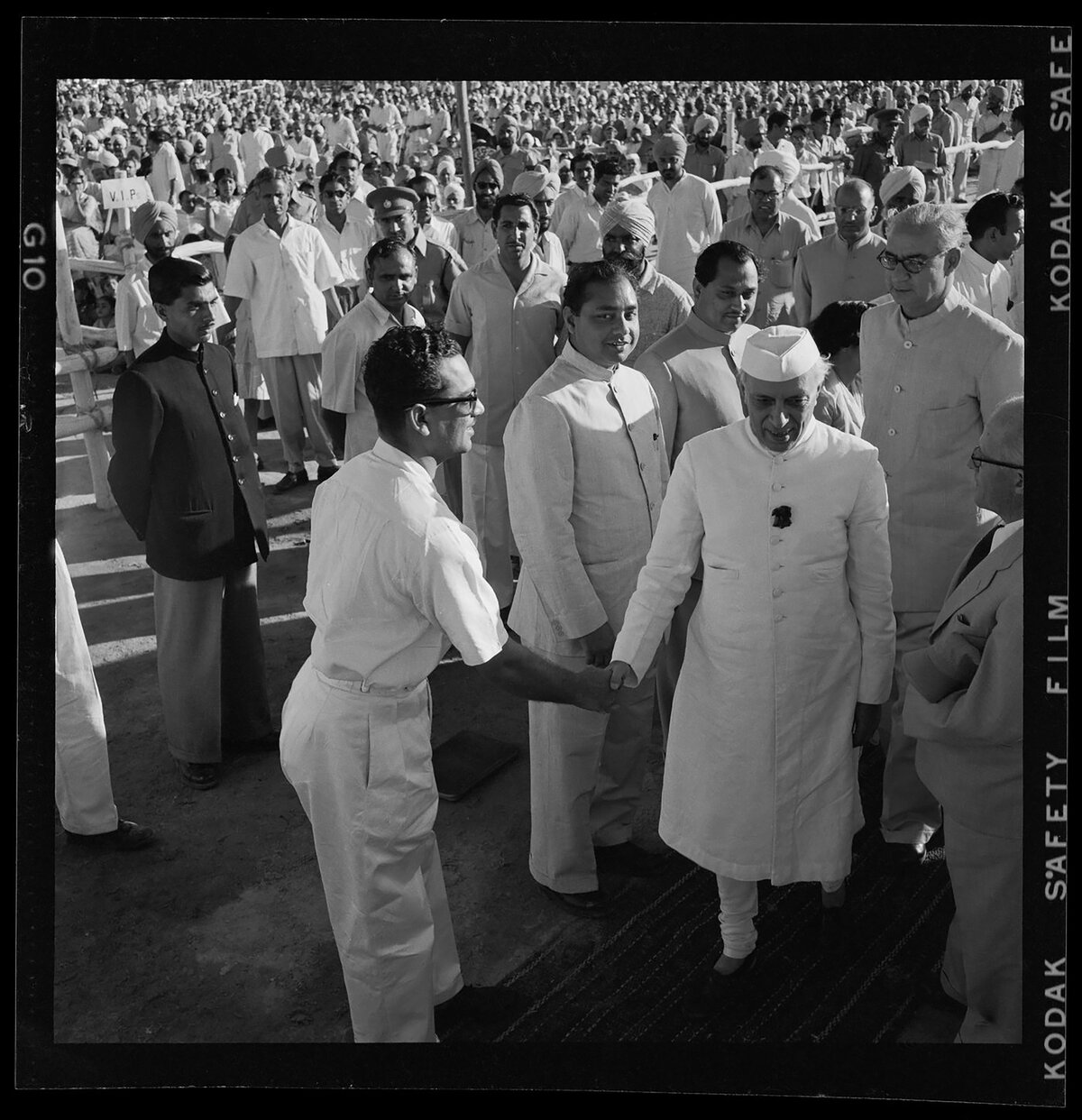

It was on the embers of this recent tragedy that Chandigarh was to come up. It was to be the new capital of Indian Punjab. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru stressed its symbolical value as a salve as well as its practical need as a sanctuary for incoming refugees. But Chandigarh was clearly to be much more.

Together with the Bhakra-Nangal Dam, described by Nehru as the ‘temple of Modern India,’ the city of Chandigarh was to embody modernity, rationality, and the country’s urban hopes for the future. 'Let this be a new town, symbolic of the freedom of India,' said Nehru of Chandigarh in July 1950, 'unfettered by the traditions of the past. An expression of the nation's faith in the future'. [ii]

Chandigarh was to help define independent India by embodying the aspirations that drove the new nation. It is not unusual for the ambitions of a new country to be made spatially visible in such a manner. The capital cities of both postcolonial Brazil and Nigeria similarly represented the two nations' alliance with modernity and their capacity for self-governance.

Chandigarh was not the national capital but, in terms of its imagining, it paralleled Brasilia and Abuja. [iii]

Image courtesy: Wikicommons.

The City as a Place

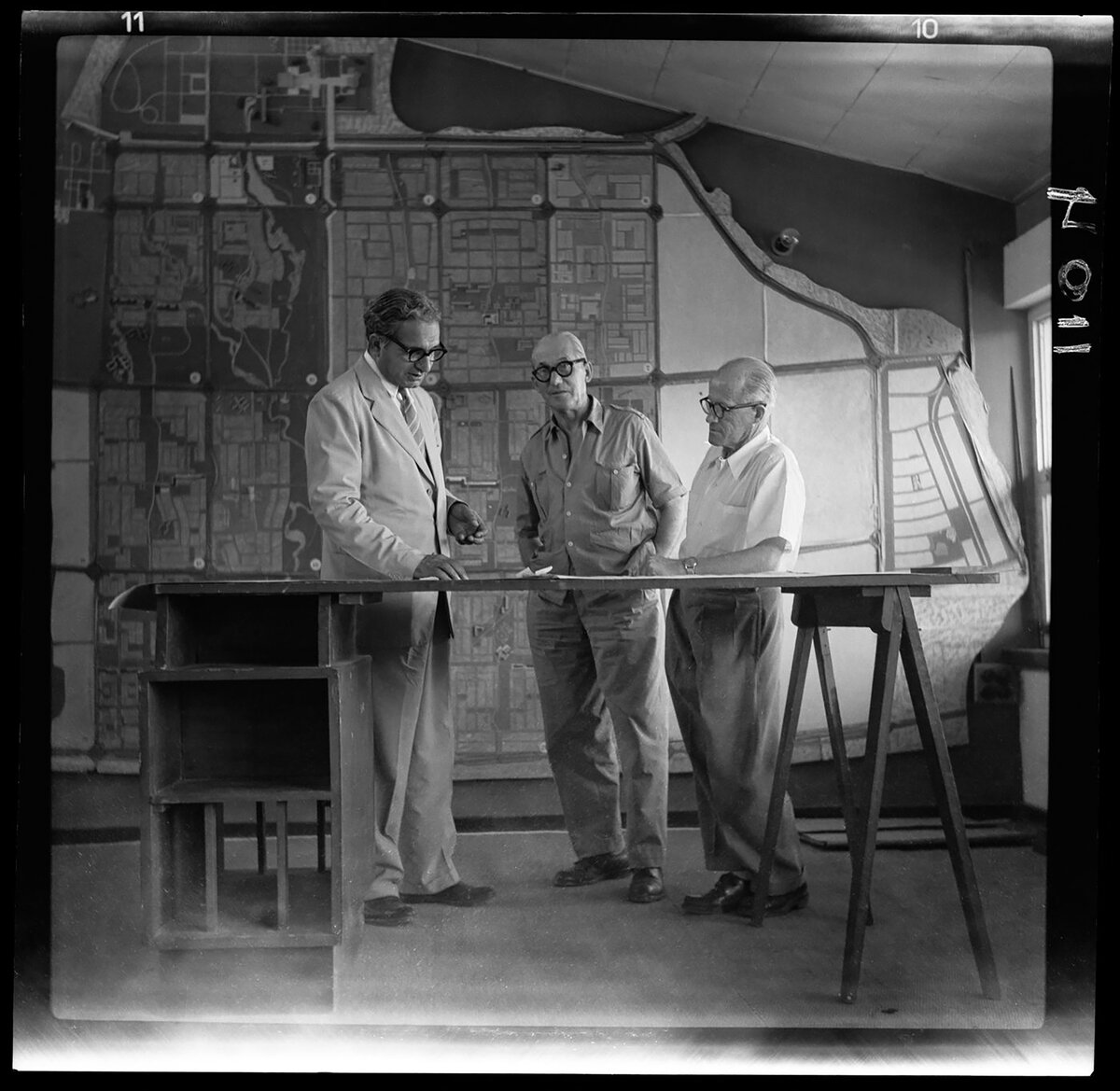

Despite being imagined as a means of delineating the nation in-progress, Chandigarh - a new city to be made from scratch - needed itself to be defined as a place. After some effort, [iv] an international team of architects was recruited to do just this. Besides the designers Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, this team came to include Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (or Le Corbusier) and Pierre Jeanneret.

At 63, Le Corbusier was by now weary of his many unrealised schemes. Although he doubted the eventual fruition of the Indian project, he saw in it a unique opportunity to implement facets of his design philosophy. He agreed to be in India for two months a year for three years and serve as the “adviser” for the city project.

Drew, Fry, Jeanneret, and he were to be assisted by a group of Indian planners and architects, including Urmila Eulie Chowdhury, J.S. Dethe, N.S. Lamba, Jeet Malhotra, B.P. Mathur, P. Mody, M.N. Sharma, and A.R. Prabhawalkar. [v]

Image courtesy: Pierre Jeanneret Fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture; Gift of Jacqueline Jeanneret.

Authoring the City

The new city, however, needed more than a master plan and blueprints for buildings. It required the object details that granted space the specificity of place.

This included the many mundane but indispensable components of inhabitation - everything from door knobs to lamp posts. Each such element would, understandably, need to match the design language the city had been crafted along.

Given the particularity of this style and the tight budget, it is not surprising that the job of designing these crucial basics fell on the people in charge of designing the rest of the city.

Among the lead architects, both Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret had previously designed furniture. Le Corbusier began experimenting with it in 1928, shortly after Charlotte Perriand joined his studio, where Jeanneret also worked. Together, the three of them went on to design a few pieces for the Villa Church, among other things.

It is because the iconic Chandigarh Chair bears resemblance to a previous piece by Jeanneret that ALL furniture produced for the city has come to be attributed to him. No evidence, however, explicitly establishes the authorship of the furniture produced for Chandigarh.

Mistaken Authorship

Both Perriand and Jeanneret’s contributions to such collaborative projects were largely overshadowed by Le Corbusier’s renown. Despite being in the background, however, one of Jeanneret’s solo designs would come to catch the eye of the owners of Knoll. The company would go on to manufacture it as the Scissors Chair in 1948.

It is because the iconic Chandigarh Chair bears resemblance to this previous piece by Jeanneret that ALL furniture produced for the city has come to be attributed to him. No evidence, however, explicitly establishes the authorship of the furniture produced for Chandigarh.

In fact, several contest the attribution of their design solely to Jeanneret, pointing out that other members of the core design team, such as Jeet Malhotra and Eulie Chowdhury, likely contributed to the conception of the furniture as well. [vi]

Image courtesy: Pierre Jeanneret Fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal; Gift of Jacqueline Jeanneret.

Importance of Ownership

This lack of clarity regarding the authorship of the furniture deserves far more attention than it has received. It stands out in a context where the architects for specific buildings and sectors in the city are all easy to ascertain.

In their discussion about Chandigarh’s Gandhi Bhavan and Kiran Cinema (designed by Jeanneret and Maxwell Fry respectively), Iain Jackson and Soumyen Bandhopadhyay highlight how important ownership was to the lead architects.

'If we are to continue together, I would like to discuss the basis of collaboration which will satisfy us...,’ they quote from a letter written by Fry to Le Corbusier. 'There is no reason why a group of buildings should not be designed by a group of CIAM architects, but I am opposed to the idea of designing individual buildings in a group or of merely carrying out your designs'. [vii]

This exchange led Le Corbusier to suggest drawing up an A-Z inventory of buildings for the city so that the architects could select commissions. Eventually, the four lead architects divided the work; Le Corbusier was to concentrate on the Capitol Complex and Fry, Drew and Jeanneret on the city sectors.

It is due to this fairly orderly division that it is easy to know which sector of the city was designed by which architect [viii]. Even additional structures built by people aside from the lead four, such as Neelam Theatre in sector 17 E, or Jagat Theatre in sector 17 A, both by Ar. Aditya Prakash, are attributed.

The little that can be gathered about the conception of the Chandigarh furniture appears to indicate a focus on its functions and how it could help with the consolidation of a large-scale urban project. It was thus more infrastructure, less artistic embellishment.

Recreation Time Labour

That the furniture is, in comparison, much harder to account for indicates that they were perhaps not understood to have been authored in quite the same manner as the city’s built environment.

This is in keeping with Dr. Vikramaditya Prakash’s comment that the Capitol architects designed furniture after work - i.e. as recreation - ‘over evening Scotch’. [ix]

Members of the architect team have described the Chandigarh office as a ‘school of architecture’; it would be in the spirit of such a place of learning to indulge in collective experiments.

There is nothing to suggest that the furniture created for Chandigarh was not the result of such informal tests and innovative exercises brought about by the need to furnish the newly built city.

Image courtesy: Phantom Hands Archive.

Furniture as Infrastructure

Notwithstanding who designed the city furniture, however, it would be fair to say that it lent Chandigarh cohesion. Like the rest of the city it was handmade by local craftspeople with local materials.

Being built for the city, the furniture fitted into it seamlessly, providing the citizens a common amenity and a connection between the residential areas and the places of work, entertainment and education. It may thus be described to have lent the city a ‘sense of place,’ what political geographer John Agnew described as essential for the transformation of a space into ‘a meaningful location’. [x]

That the furniture managed to evade attention despite playing such a pivotal role in the city’s actualisation is perhaps indicative of how deeply it was immersed in its surroundings - enough to disappear into it.

Being a fundamentally relational concept, infrastructure is defined by its ‘embeddedness,’ writes sociologist Susan Leigh Star. Typically, it is ‘sunk into and inside of other structures’, thereby making it invisible. That is until it suffers a breakdown. [xi]

It is telling that Chandigarh’s furniture came to attention only once it had fallen apart and been discarded. The little that can be gathered about it appears to indicate a focus on its function. In more ways than one it seems more infrastructure, less artistic embellishment.

Relations Between Things

It is telling in this regard that Chandigarh’s furniture came to gain attention only once it had fallen apart and been discarded. The little that can be gathered about the conception of the Chandigarh furniture appears to indicate a focus on its functions and how it could help with the consolidation of a large-scale urban project. It was thus more infrastructure, less artistic embellishment.

Often, infrastructure consists of things which, though objects themselves, are most significantly the relation between things. The furniture in Chandigarh, accordingly, served to constitute the relation between the people who inhabited the city and the buildings built to make the city habitable. [xii]

Infrastructure can and does exist as forms separate from their purely technical functioning, and may very well be seen as aesthetic vehicles. The furniture from Chandigarh has certainly succeeded in transitioning from the former to the latter.

But has its new autonomous identity as objects symbolising wealth, taste, and cultural capital been gained at the cost of the social imagination it had been a result of? Given their close relation with their context and the place they belonged to, what do infrastructural objects carry with themselves once displaced? What openings do they leave behind?

Endnotes:

[i] See Phantom Hands’ interview with Vikramaditya Prakash here.

[ii] From Ravi Kalia, Chandigarh: The Making of an Indian City. (1999)

[iii] See Ganeshwari Singh, Simrit Kahlon, and Vishwa Bandhu Singh Chandel’s "Political Discourse and the Planned City: Nehru’s Projection and Appropriation of Chandigarh, the Capital of Punjab." Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109.4 (2019): 1226-1239.

[iv] Several architects, including Albert Mayer and Otto Königsberger, had previously been consulted for the project. Mayer even devised an initial master plan of the city. Corbusier’s final plan was based on this.

[v] Chapter 2, Chandigarh: The Making of an Indian City

[vi] Chandigarh Chairs: Missing Histories, a discussion conducted by Nia Thandapani, Petra Seitz and Gregor Wittrick for the Bangalore International Centre on 24/09/2020 explores this in great depth. Recording of the video event maybe seen here

[vii] Iain Jackson, and Soumyen Bandyopadhyay. "Authorship and modernity in Chandigarh: the Ghandi Bhavan and the Kiran Cinema designed by Pierre Jeanneret and Edwin Maxwell Fry." The Journal of Architecture 14.6 (2009): 687-713.

[viii] CHD Chandigarh by Vikramaditya Prakash is a useful pocket architectural guide which provides details about the making of the city and lists sectors in terms of their architects. See it here.

[ix] This came up during Phantom Hands’ interview with Vikramaditya Prakash.

[x] Quoted by Tim Creswell in Place: A short introduction. John Wiley & Sons, (2013)

[xi] Susan Leigh Star "The Ethnography of Infrastructure." (American behavioral scientist 43.3 (1999): 377-391)

[xii] This discussion borrows from Susan Leigh Star’s "The Ethnography of Infrastructure." and Brian Larkin’s ‘The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure’ (Annual review of anthropology 42 (2013): 327-343.)

In Conversation With Professor Vikramaditya Prakash: On the Authors of Chandigarh

Dr. Vikramaditya Prakash is Professor of Architecture at the University of Washington, Seattle and grew up in Chandigarh. Here he discusses the first generation of Indian Modernists who worked on the architecture & furniture of Chandigarh.

Read More

Upholding Europe’s Legacy: From Chandigarh’s City Furniture to ‘Pierre Jeanneret’s Chairs’

The quiet extraction of heritage furniture from Chandigarh spoke of the Indian government's disregard and neglect. But it also revealed a profit chain linking officials, antique dealers, and powerful Euro-American institutions.

Read More

Upholding Europe’s Legacy: From Chandigarh’s City Furniture to ‘Pierre Jeanneret’s Chairs’

The quiet extraction of heritage furniture from Chandigarh spoke of the Indian government's disregard and neglect. But it also revealed a profit chain linking officials, antique dealers, and powerful Euro-American institutions.

Read More

In Conversation With Ar. Shivdatt Sharma: On the Chandigarh School of Modernism

Architect Shivdatt Sharma is one of the premiere modernist architects of India. He started out in the Chandigarh Capital Project Team under the leadership of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret.

Read More