The Aditya Prakash Collection: Seats for Conversation

The Aditya Prakash Collection on display at Phantom Hands.

Parni Ray

18.05.2023

Born in 1924 in the north Indian city of Muzaffarnagar and trained in London as an architect, Aditya Prakash was a junior architect at the Chandigarh Capital office under Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret. His later work reflected the modernist ideals imbibed in these early years of training and, along with the likes of Achyut Kanvinde and B.V. Doshi, Praksh is often described as one of India’s first modernist architects. Despite his repute, however, much remains unknown about his oeuvre, which includes his experiments with furniture making – showcased in the Aditya Prakash Collection by Phantom Hands.

Building Independent India

In 1950 Le Corbusier, by then venerated as a modernist genius, was appointed by the government of a recently-free India to design a ‘modern new city’ - Chandigarh. The city was India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru’s dream project and was to embody modernity, rationality, and the country’s urban hopes for the future.

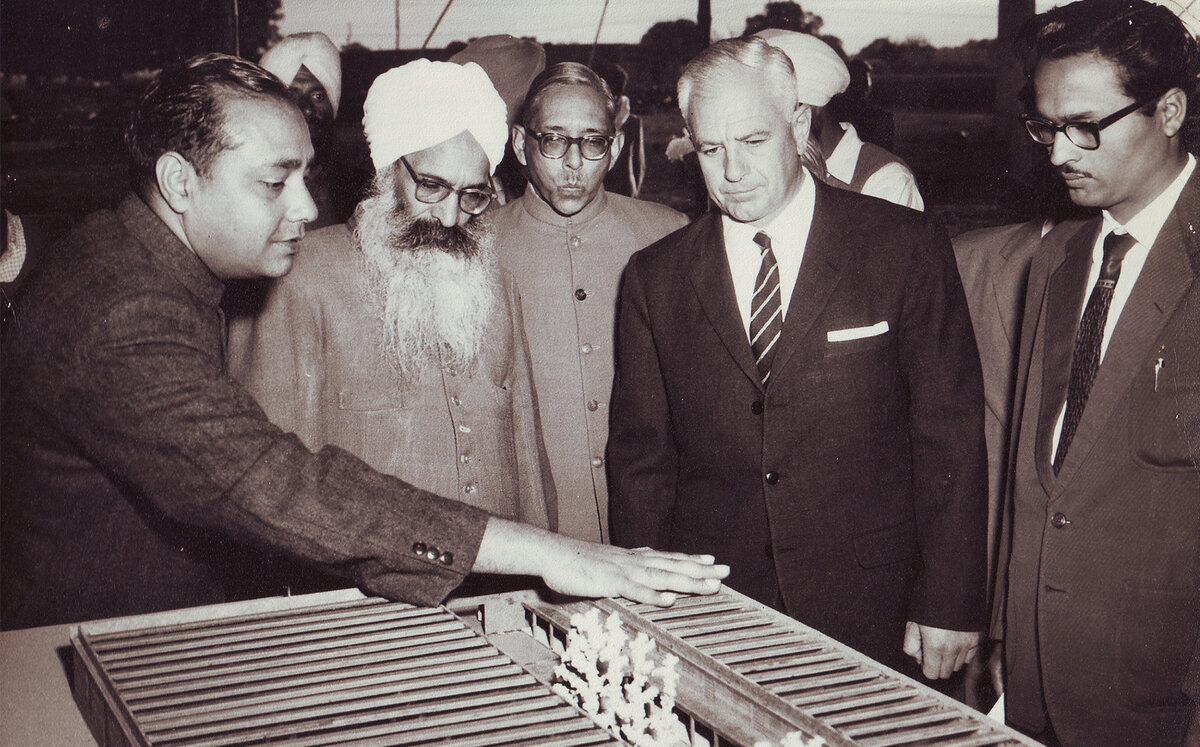

Le Corbusier came onboard as the architectural advisor. Pierre Jeanneret, Maxwell Fry, and Jane Drew joined him as senior architects. A group of Indian engineers and junior architects were placed directly under their supervision.

The appointment of this last set was strategic. Aside from serving as a symbol of the ethos of independent India, Nehru imagined Chandigarh to be a fertile ground for learning for young Indian professionals. Trained on-ground by stalwarts such as Le Corbusier, Nehru envisioned these men to then help him build India.

Among this young group was 28 year-old architect Aditya Prakash. Prakash moved to London shortly after India's independence to study at the London Polytechnic (now Bartlett). Previously he had been enrolled at the Delhi Polytechnic (now the School of Architecture and Planning).

In 1951, just before joining the Chandigarh Capitol Project team as a junior architect, he became an A.R.I.B.A (Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects). Prakash stayed in this role at the Chandigarh architect’s office for a decade, from 1952 to 1962. During this tenure, he designed a number of significant buildings across the city, including the District Courts in Sector 17, Tagore and Neelam Theatre, and the Chandigarh College of Architecture.

Furniture as Building Detail

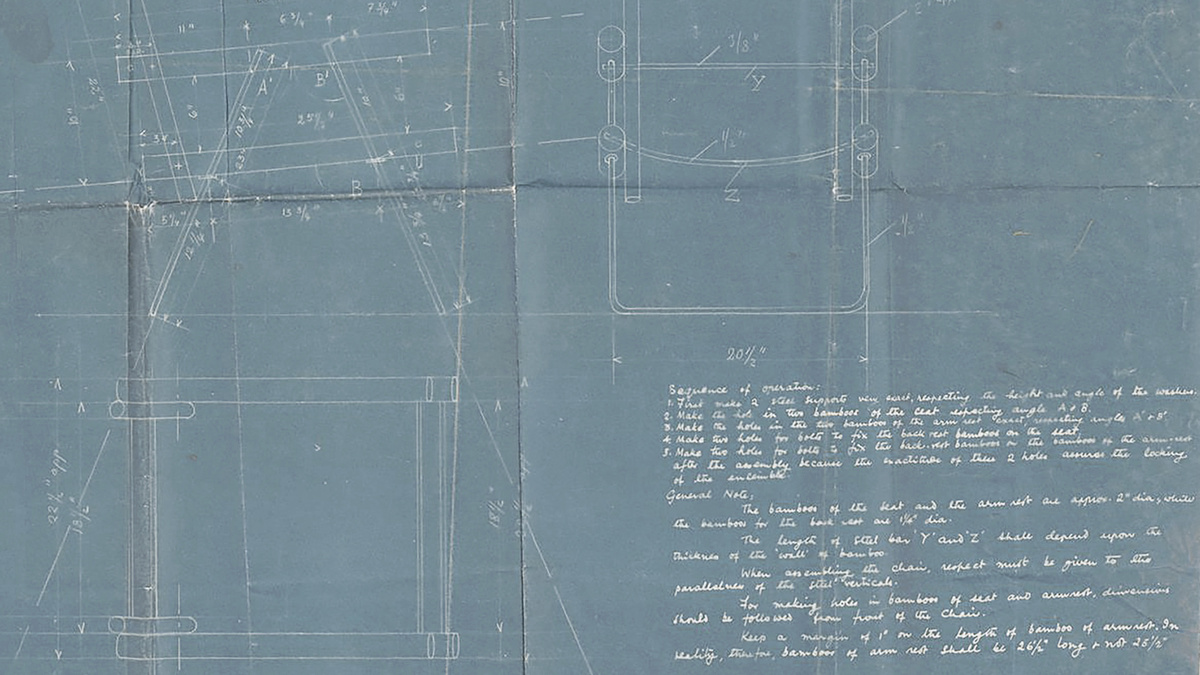

It was standard for the furniture in every city building to be designed at the architect's office in Chandigarh. The logic was simple, money was meagre and making furniture locally, with local materials and labour was cheaper than buying readymades.

It also allowed for the meticulously-worked-out aesthetic of the city to be maintained across quarters, beyond the built environment, even within interior spaces. In the hands of the architects, the furniture became a building detail, infrastructure.

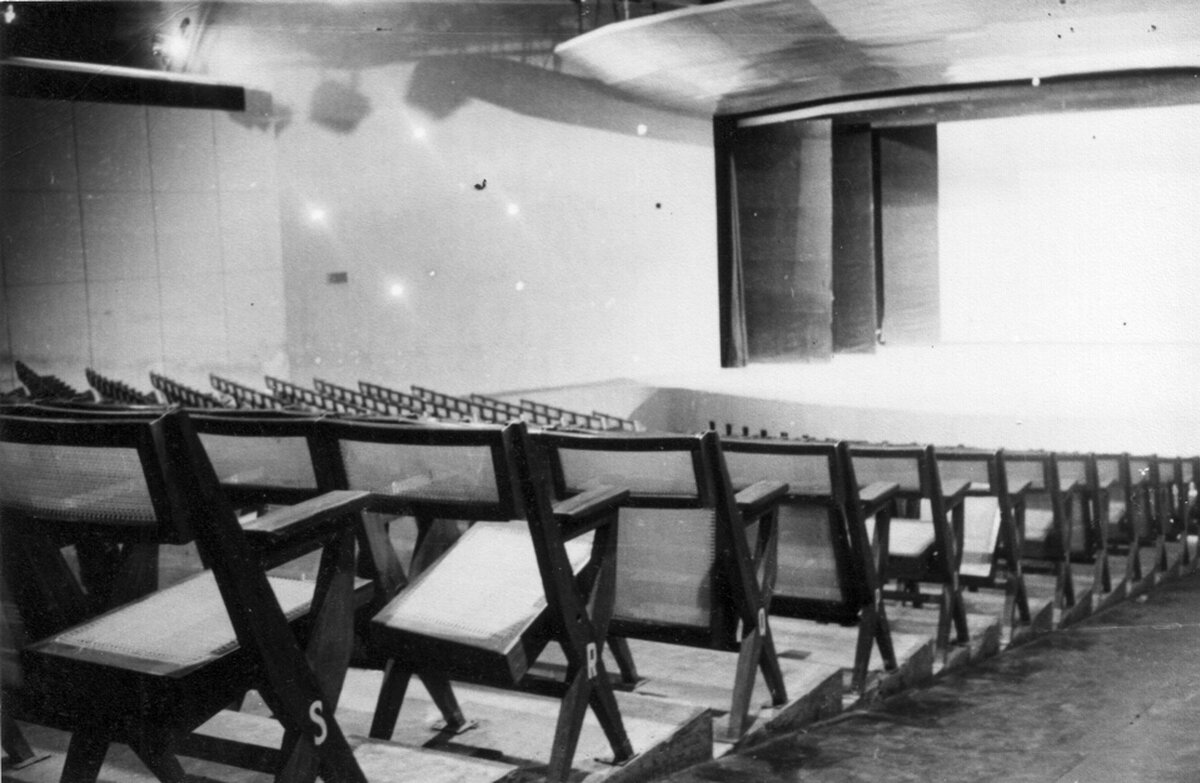

Like most of his colleagues, Prakash’s furniture designs drew freely from Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand’s work, modifying them to suit Chandigarh’s context. Among the public furniture he designed were the chairs at Tagore theatre, constructed to celebrate Rabindranath Tagore’s birth centenary in 1961. A long-time aficionado of the theatre, Praksh had aimed to make the chairs in the 600-seater auditorium comfortable ‘but not so comfortable as to allow the audience member to doze off’. He worked out his plan for the chairs on a chalkboard wall in his office. Most of the other furniture he designed on the job were similarly drawn to scale and put through a vetting process before being executed with the help of a carpenter.

Aditya Prakash Collection by Phantom Hands

Aside from public furniture made for the city of Chandigarh, Prakash also designed things for his personal use at home. Tables, dining chairs, corner stools, outdoor seating, even a vanity stand. Almost all of these maintained the mid-century modern style that became synonymous with Chandigarh.

In early 2021, when the Phantom Hands team started toying with the idea of re-editing Prakash's furniture, they zeroed in on these domestic pieces. After discussions with his son - architect, architectural historian Vikramaditya Prakash - they decided on three items, a wooden lounge chair, a dining chair and a unique bent metal chair with a jute seat, the 'continuous line' chair.

Unlike the other selections, the 'Continuous Line Chair', was used outdoors. 'My Mother insisted that we didn't bring it indoors', Vikram had explained laughing. The distinctive chair was made by bending and welding a single 5 mm steel rod over and over again. With its woven jute seat it brought together two unsung Indian craft traditions - metal work and weaving.

‘Back then chair weavers would go door-to-door looking for work,’ says Vikram, reminiscing about his childhood in Chandigarh. ‘This was before the invasion of plastic so they mostly worked with jute and cane.’

Although metal was a departure from the materials typical to Chandigarh’s furniture vocabulary, it wasn’t outside Aditya Prakash’s oeuvre. Earlier, he had also designed some foldable metal pipe beds. 'We used these during the summer, when we typically slept outside', Vikram shared. During the day, the beds were folded and stacked on the window sill, he said.

The Continuous Line

The name, ‘Continuous Line’ draws from Vikram’s book on his father. Its significance in Aditya Prakash’s story is lent by the architect’s seeming artistic impulse to generate form using, literally, one continuous line. ‘Repeatedly,’ Vikram writes, ‘Prakash would return to the one continuous, twisting and turning line to create art, explore geometric proportion, and even design furniture’.

His many interests frequently took him beyond the boundaries of his discipline. But this didn’t daunt Prakash. Shaped by early 20th C. Enlightenment values, he viewed all aspects of his work to be ‘multiple dimensions of a single quest’. This, writes Vikram, was the ‘one continuous line’ in his life.

Prakash was a salaried government official from 1951 to 1989. He was appointed four years after India’s independence, just as the republic was finding its feet, learning to toddle. His status as a state employee lent him a sense of profound responsibility. Under the leadership of Nehru, modernists like him understood their task to be nothing less than actualising the dream of a new, post-colonial, sovereign nation. The fervour of India’s Independence Movement was still in play and the individualistic ideals of identity and authorship felt too trivial in the face of a moment in history that was far bigger than the self.

Remaking Prakash’s furniture is an attempt at lending his work autonomous recognition. Symbolically, it is also an effort at recognising the work of several others like him, whose individual efforts helped deliver a collective dream. Foregrounding such work is critical. It helps decentre narratives built around India’s modernist emblems, much of which remain understood as the product of the singular genius of European figures such as Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret.

Recognising the role played by the labour and ingenuity of local players in the fruition of these emblems changes our relationship with them. Not only does it allow us to truly claim them, it also makes us see them as our heritage, a vital part of our nation’s history that needs preserving.

Reclaiming Legacy

In 2008 Aditya Prakash's Tagore Theatre was demolished, a renovated structure took its place. A second theatre designed by him had been pulled down previously. Several of Prakash's other creations, many of them cultural landmarks in Chandigarh, remain at risk of being similarly obliterated.

Some would say the modernist moment that Prakash belonged to has long since passed. Like the buildings built during the time, its ideals have crumbled under the winds of change. But it isn’t just architectural entropy that has put the legacy of people like him at risk. ‘Many structures from the 1950s, 60s and 70s - and not just Prakash’s - have already been destroyed and replaced with the latest icons of globalisation,’ Vikram writes. ‘The problem is not only the age and potential outdatedness of the structures, but also a sense of hostility cultivated by strong, nationalist forces against the Nehruvian age and its values.’

There may be some merit in reexamining the initial intentions of the newly independent India, the values Prakash and others tried to uphold through their designs, at this juncture. Could these be reassessed, engaged with anew in ways beyond academic dialogue or polemical critique? That’s the question posed by the Aditya Prakash Collection by Phantom Hands. A couple of old chairs, re-edited for today’s context and sensibilities, appear a good site to begin such a conversation.

Featured Products

See More

In Conversation With Professor Vikramaditya Prakash: On the Authors of Chandigarh

Dr. Vikramaditya Prakash is Professor of Architecture at the University of Washington, Seattle and grew up in Chandigarh. Here he discusses the first generation of Indian Modernists who worked on the architecture & furniture of Chandigarh.

Read More

The Genesis of the Chandigarh Chair: Furniture as Infrastructure

There are several things unique about the furniture made for the city of Chandigarh in the 1950’s. The most striking among these is that they were conceived at the same time as the city, as a component of its master plan.

Read More

Upholding Europe’s Legacy: From Chandigarh’s City Furniture to ‘Pierre Jeanneret’s Chairs’

The quiet extraction of heritage furniture from Chandigarh spoke of the Indian government's disregard and neglect. But it also revealed a profit chain linking officials, antique dealers, and powerful Euro-American institutions.

Read More