A Reading of ‘The Architecture of Shivdatt Sharma’ and ‘A Concise History of Modern Architecture in India’

Jon Lang's book, 'A Concise History of Modern Architecture In India,' published by Permanent Black, 2002.

Parni Ray

06.11.2020

The writer pours through Vikramaditya Prakash’s 'The Architecture of Shivdatt Sharma' and Jon Lang’s A Concise History of Modern Architecture in India.

Both these books delve into the architectural identity of modern India; the first via the work of a single architect - S.D Sharma - located primarily in Chandigarh, and the other book via the work of several architects, local and international, across the country.

Modernist design (like modernism itself) is often understood to have been borrowed by India from the West. But the flow of ideas is not unidirectional and the source of modernism is not easy to infer, Vikram and Jon suggest.

To be modern, Jon Lang proposes, is to believe that there are better ways of doing things. ‘A modernist is someone whose whole line of thinking owes much to the spirit of enlightenment and the belief that the world can be improved,’ he writes. In keeping with this, he points out, modernist architects tend to see architecture as a means of improving the lives of people.

Defining a Modern India

It is not surprising that Indian modernist architecture had its moment at the dawn of the nation’s birth. Aspirations of betterment underscored the country’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru’s 19 years in office. In his celebrated speech on the eve of India’s independence in 1947 he had stated, ‘as long as there are tears and suffering, so long our work will not be over...And so we have to labour and to work, and work hard, to give reality to our dreams’.

This work came to take the form of a variety of developmental projects, which Nehru saw as a means of defining the new nation and improving the life of its citizens. They included the construction of cities, public housing, as well as buildings for institutions that would help constitute independent India. Much of this was made possible by architects who described themselves as modernists.

Nation Building in Independent India

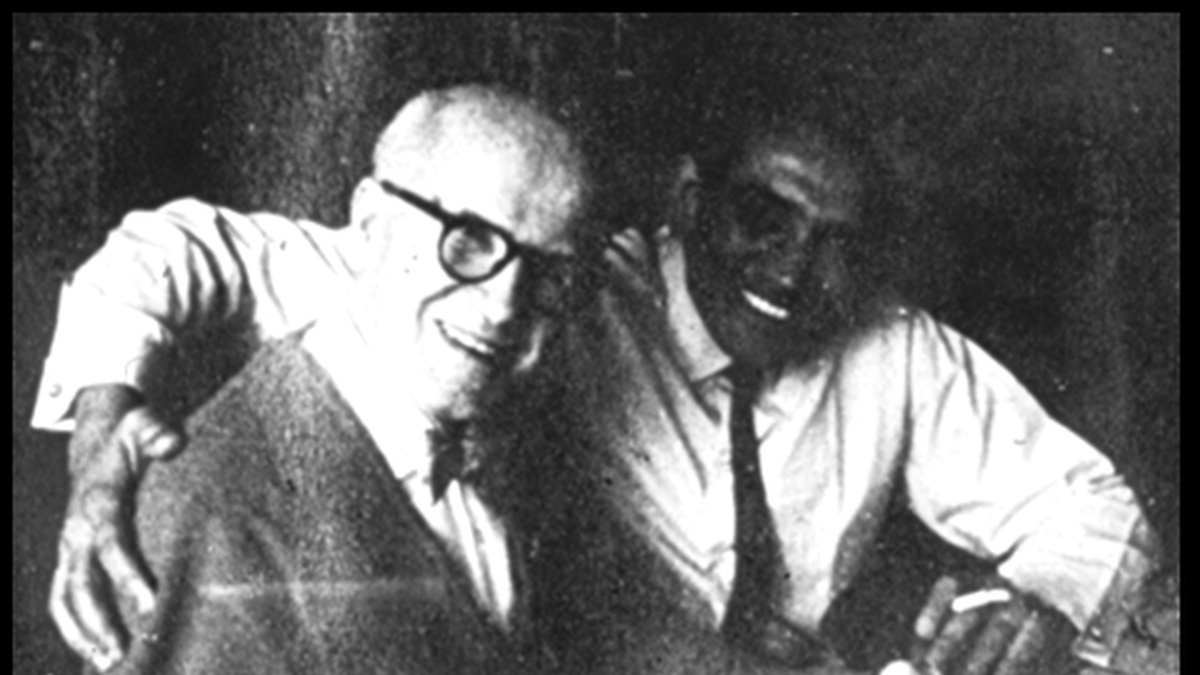

Shivdatt Sharma, the subject of Vikramaditya Prakash’s monograph, was among them. Uprooted from Lahore by the Partition, Sharma joined the Capital project team early on. Over the years, he has come to credit his training as an architect to the years spent here, and to the mentorship of Pierre Jeanneret and Le Corbusier.

He says he carried much of what he learnt to Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO), where he was appointed the Chief Architect in 1973. The nine years he held office here were to prove a prolific period; while here he designed several buildings that came to define ISRO, one of the most significant scientific institutions in post-colonial India.

Like Sharma, several others from the Chandigarh architect team - including J.K Chowdhury, Jeet Malhotra and Aditya Prakash - would go on to be involved with institutional projects across the country. Le Corbusier’s impact on their work, as well as others they in turn influenced, was considerable, Jon suggests.

But before him there was the Bauhaus School of Design.

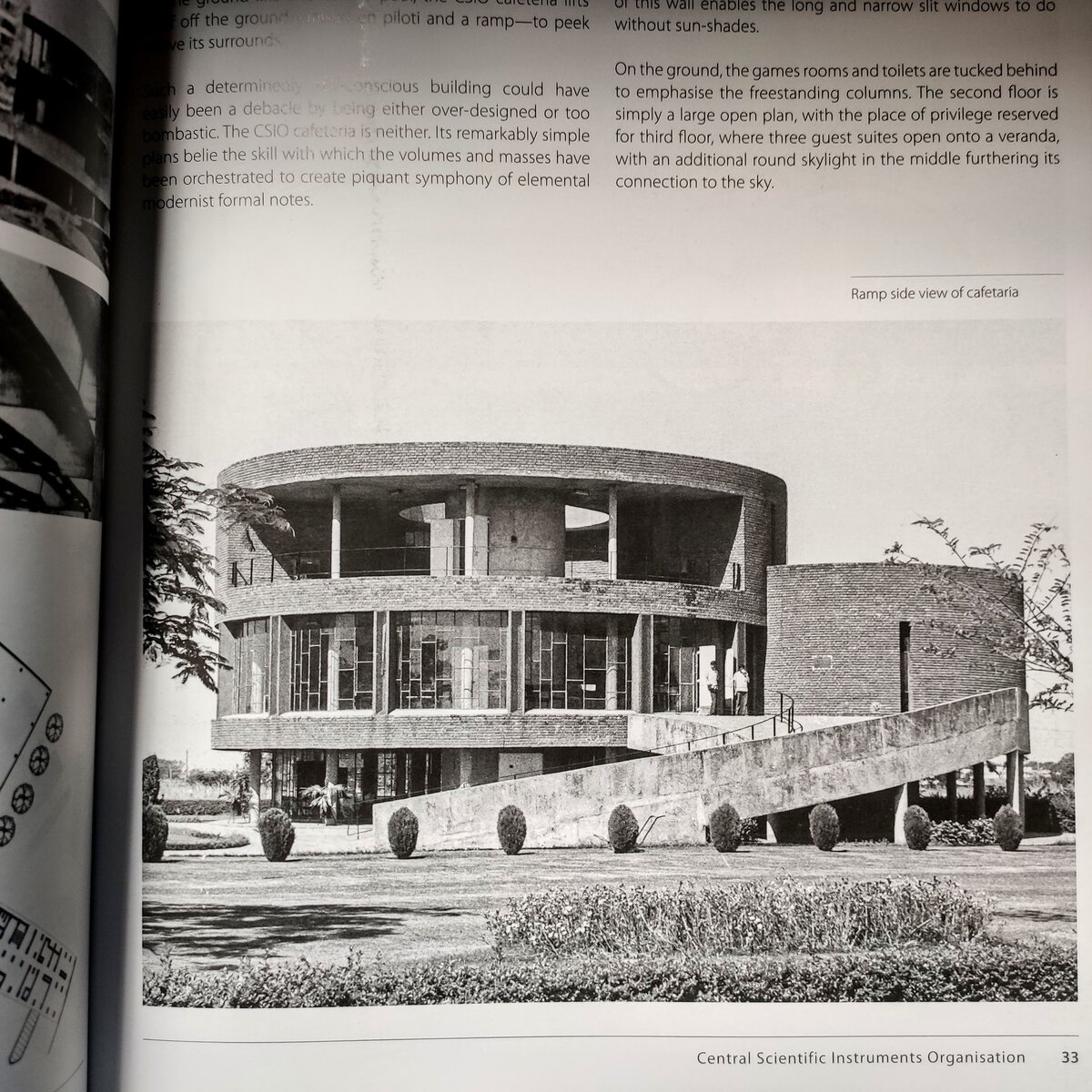

Image courtesy: 'The Architecture of Shivdatt Sharma'.

Influence of Bauhaus Design School

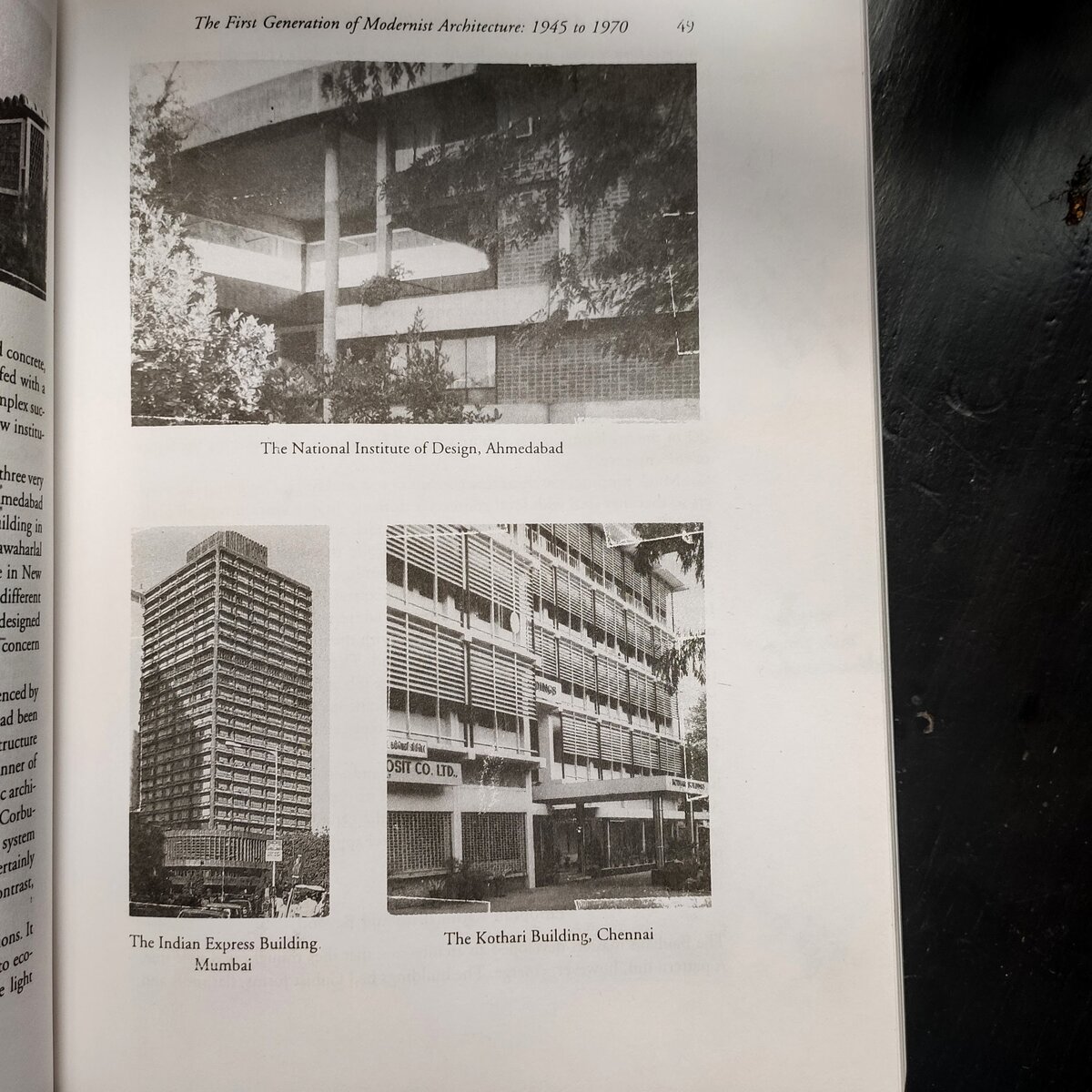

The Bauhaus exhibited in Calcutta in 1922. But while that made its impression on fine artists in the country, its effect on Indian architecture was negligible, Jon writes. The built environment in India was impacted by the Bauhaus due largely to the work of young architects who had returned to India following their training in the U.S.

Several people, including Gautam and Gira Sarabhai, who were instrumental in establishing the National Institute of Design, studied architecture in the U.S. and came back to practice in India during this time.

Habib Rahman and Achyut Kanvinde, who had studied under Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University respectively, stood out among them. Their work in Delhi, Calcutta, and Ahmedabad marked a pivotal moment for Indian Modernist architecture, Jon writes.

Image courtesy: Wikicommons.

Experiments in Modern Design

Soon after his return from the United States and his work on the striking Gandhi memorial in Barrackpore, Rahman was scouted by Nehru and invited to join the Central Public Works Department (CPWD). As part of the CPWD, he designed public housing colonies, governmental offices, as well as institutional buildings.

Kanvinde had been appointed the Chief Architect of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research in 1947. He designed several buildings while in this position, including the CSIR headquarters in New Delhi as well as several significant institutional buildings, such as that of the Physical Research Laboratory (Ahmedabad), associated with scientific research in the country.

These would all prove crucial experiments in the field of modern design and go on to define the nation's landscape, both directly and indirectly.

Image caption: Wikicommons.

New Approaches to Modern India

These experiments, Jon points out, were facilitated by a desire shared by the likes of Sharma, Rahman, and Kanvinde to bring new approaches to new India. That they continued with the stylistic features associated with their mentors (Le Corbusier, Jeanneret, Gropius) had to do with several factors. The most important among which was the simplicity of the structural and constructional ideas associated with them, Jon writes.

But while their work did bear a stamp of their respective mentors at the outset, these architects were an eclectic group whose oeuvre as designers evolved considerably with their experience in the country. ‘Emulating’ styles is quite common among young architects, points our Jon.

Despite this, the influence of stalwarts like Le Corbusier and Gropius has often led people to see Indian architectural modernism as ‘derivative’. A big reason for this, Jon writes, is that modernism itself continues to be understood to ‘belong’ to the West in its original form.

Image courtesy: Wikicommons.

Where Does Modernism Belong?

This notion can be misleading, both Vikram and Jon assert. For one, it obscures the fact that ideas from India have continued to influence the West. Unlike the influence of European and American modernism on India, the counterflow is harder to discern because it is neither as well documented, nor as widely discussed.

The narrative that gets upheld instead, Vikram points out, is inherently colonial and represents local designers from India as ‘copyists’ and their former colonial overlords as the ‘original thinkers’.

It is this, Vikram suggests, that has led to the near obfuscation of the creative labour local architects such as Shivdatt Sharma put into Chandigarh, which continues to be identified as the creation of European architects. Given the little claim that Shivdatt and others have had on the making of Chandigarh, it is no wonder that them drawing from the city’s architectural vocabulary later is seen as them borrowing from Le Corbusier’s work, not their own.

Image courtesy: Wikicommons.

Global Cosmopolitanism

To allow for a more multivocal understanding of modernism that can make room for varied makers, Vikram proposes it be re-evaluated as a ‘global heritage, a global cosmopolitanism at work’. Rather than seeing it as a singular European creation born out of a singular European history - the original version of which can only be located in Europe - Vikram suggests modernism be seen as a consequence of the colonial world and its aftermath.

In this reversed worldview, not only are the specific circumstances in post-colonial India responsible for the modernist architecture that prospers there, the idea of ‘original’ modernism and emulation itself is dissipated.

As a result, a variety of authors - not just American and European ones - are allowed to claim the many stylistic features of architectural modernism. And several architectural expressions can claim to be authentically modern.

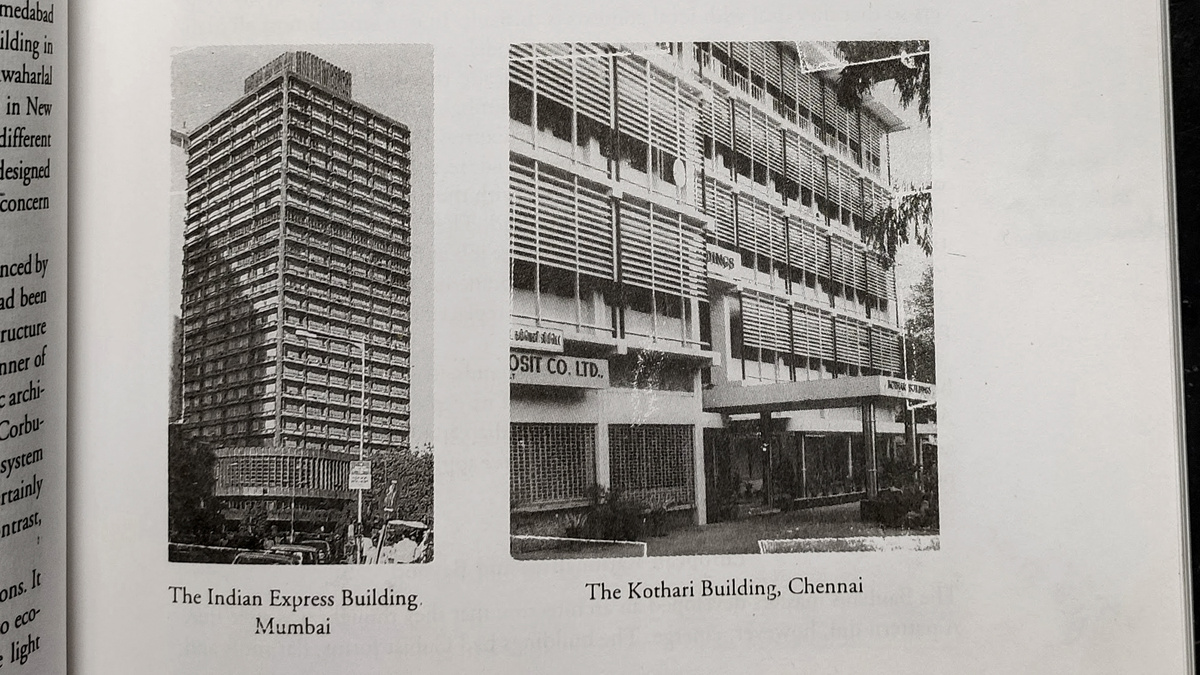

Image courtesy: 'A Concise History of Modern Architecture in India'.

In Conversation With Ar. Shivdatt Sharma: On the Chandigarh School of Modernism

Architect Shivdatt Sharma is one of the premiere modernist architects of India. He started out in the Chandigarh Capital Project Team under the leadership of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret.

Read More

In Conversation With Professor Vikramaditya Prakash: On the Authors of Chandigarh

Dr. Vikramaditya Prakash is Professor of Architecture at the University of Washington, Seattle and grew up in Chandigarh. Here he discusses the first generation of Indian Modernists who worked on the architecture & furniture of Chandigarh.

Read More