The National Institute of Design: Making a New Nation, By Design

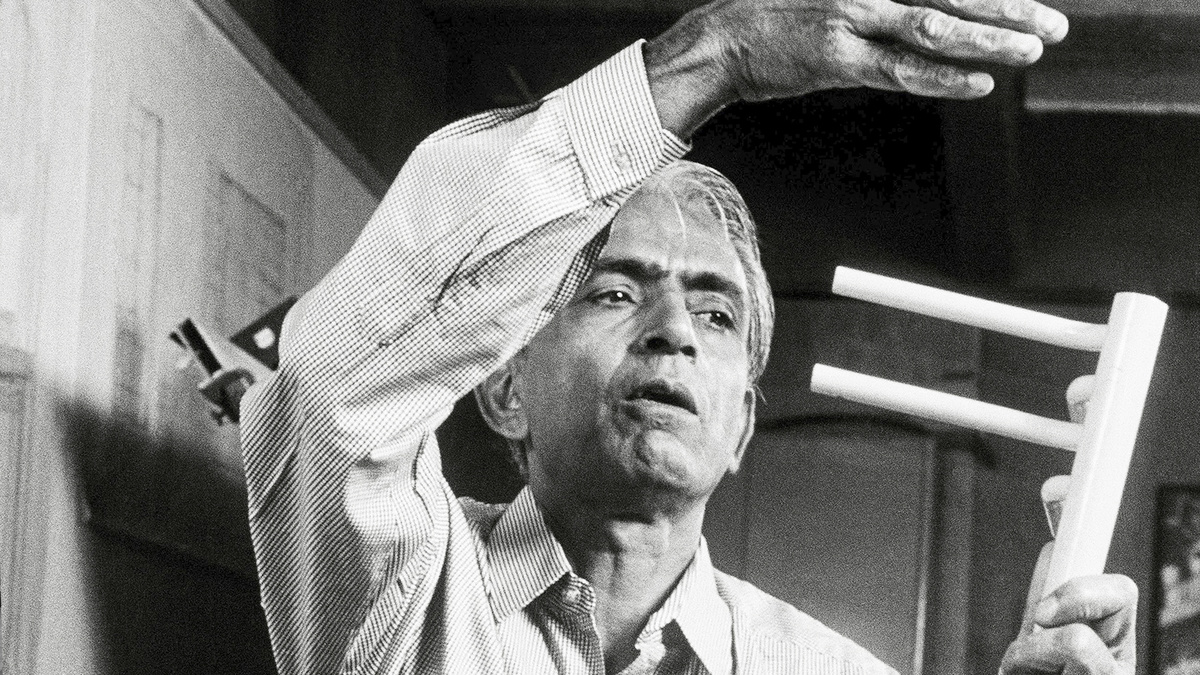

Interiors of the workshop at NID, P.M. Dalwadi, 1967. Image courtesy: National Institute of Design (Archive), Ahmedabad.

Parni Ray

13.11.2020

In 1961, an independent India established its premiere design school, the National Institute of Design, in the city of Ahmedabad. Several agents, both local and global, were instrumental in its creation.

Besides India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, its conception and existence owed much to the illustrious Sarabhai family and the US philanthropic agency, Ford Foundation.

It would also be aided by the newly independent India’s status as a politically non-aligned force in the heydays of the cold war and the international alliances this would make possible.

Master Modernist's Influence

When approached by Indian authorities to design the new city of Chandigarh, Le Corbusier - architecture’s ‘Master Modernist’ - had initially brushed aside the request to come to India. There was no need for him to travel so far, he had pointed out, ‘your capital can be built right here, at 35 rue de sèvres à Paris’.

After much coaxing however, he finally agreed to drop by every six months to see how the project was evolving. [i]

These visits proved more fruitful than Le Corbusier had probably anticipated. Besides Chandigarh, they also led to him designing several notable buildings in the city of Ahmedabad.

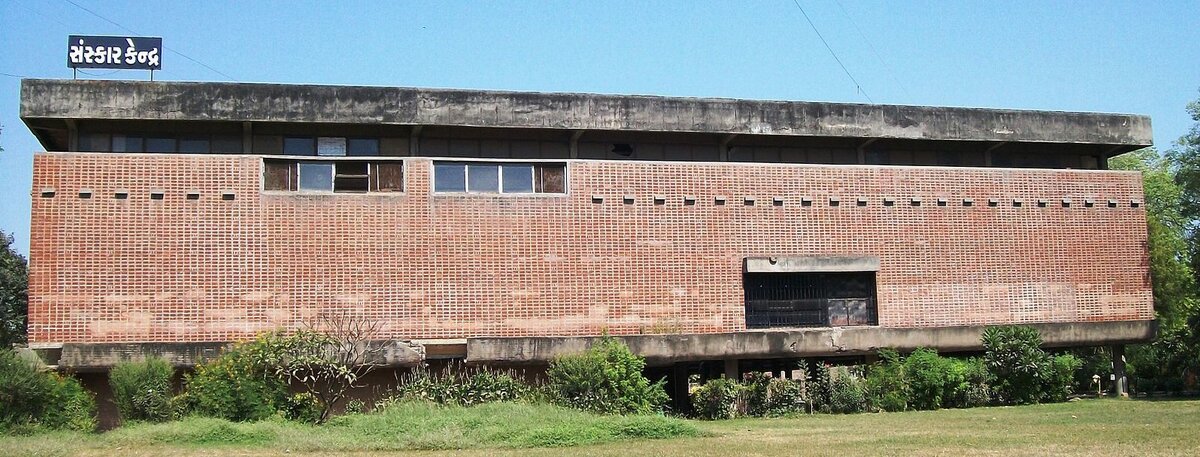

Corbusier visited Ahmedabad on the invitation of the city’s wealthy mill owners and mahajans, all eager patrons of modern architecture and technology. Between 1951 and 1957 he would design five buildings here. These included the Sarabhai Villa, the Mill Owners’ Association building and the city museum, Sanskar Kendra.

Image courtesy: Wikicommons.

Modernist Vision of India

It was in the attic of the Sanskar Kendra that siblings Gautam, Gira and Vikram Sarabhai would deliberate the idea of an institute of design a few years later with Dashrath Patel, Kumar Vyas and others.

On their initiative, and with the assistance of their illustrious family and Ford Foundation, the Government of India would eventually establish the National Institute of Design (NID) in 1961.

The making of India’s premiere design school corresponded perfectly with Jawaharlal Nehru’s modernist vision of a new India. Internationalism, innovation and a spirit of inquiry underscored its birthing. As did India’s newly adopted political stance as a non-aligned force in the heydays of the cold war. Together these factors defined independent India’s attitude towards design in the mid-century and paved the way for what may be described as a modern Indian design lexicon.

The Roots of the Sarabhais

The Sarabhais, who played a pivotal role in the inception of NID, were no ordinary Indian family.

The grand patriarch at its helm then, Seth Ambalal Sarabhai, owned one of the oldest textile mills in India and introduced various technological innovations in the Indian textile manufacturing industry. He also headed the supremely successful Sarabhai Group of Companies, which collaborated with enterprises in the United States, Switzerland and Germany.

Staunch Gandhians, his family was closely involved in the Indian Independence Movement and shared a close relationship with both Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. It was no surprise that post-independence, much of this family got involved with new India’s many developmental projects.

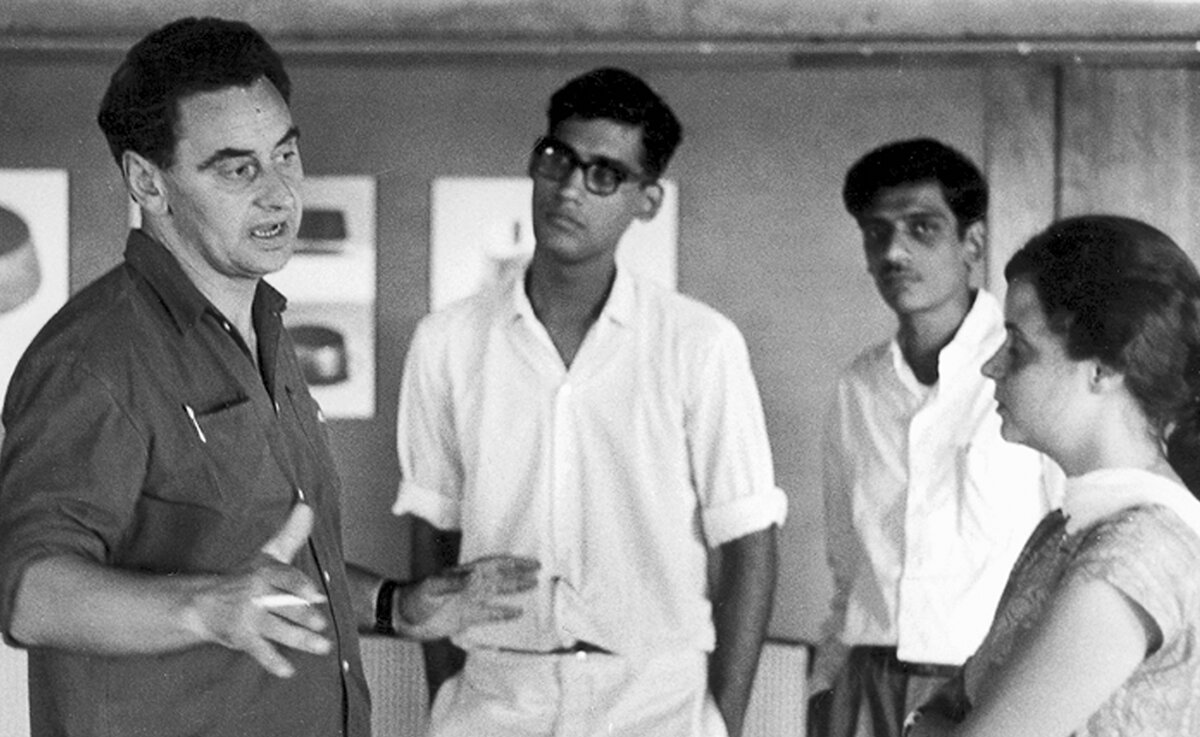

Image courtesy: National Institute of Design-Archive, Ahmedabad.

The Inception of NID

His daughter Gira and sons Gautam and Vikram, who all had an exceptionally privileged and progressive upbringing, were quickly drawn to institution making. Vikram, a physicist trained at Cambridge, founded the Physical Research Laboratory, the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) and later, played a major role in the creation of the Indian Institute of Management.

Gira and Gautam attended celebrated architect Frank Llyod Wright’s atelier in Taliesin, USA, and both would help conceive NID and design its campus.

The Sarabhai siblings and the rest of their family were close to several luminaries. Besides Gandhi and Nehru, they were in correspondence with Rabindranth Tagore, Subhash Chandra Bose and other significant political and cultural figures in pre-independence India.

Thanks to their cosmopolitan lifestyle and business interests overseas they were also well connected with various foreign artists, thinkers, designers, and innovators. A long list of such women and men - among them John Cage, David Tudor, Robert Rauschenberg, Jean Erdman, Alexander Calder and Louis Kahn - even visited and lived with the family in their Ahmedabad home. [ii]

The Sarabhais' extensive connections were instrumental to NID from the very beginning. In 1955, one of their friends, Pupul Jaykar, met Ray and Charles Eames at an exhibition on Indian textiles and ornamental arts at the Museum of Modern Art.

Jaykar was the founder of the Indian Handlooms and Handicrafts Export Council and knew that the Indian government was considering establishing an institute of design at the time. With the Sarabhai siblings, she advised them to invite the Eames’ to visit India and provide recommendations for a design training programme.

Local Design, Global Allies

The Eames’ India Report, widely regarded as the raison d’être of NID, was far from the feasibility report the Indian government expected it to be. While the authorities assumed it would provide practical solutions and possibly a plan of action, Ray and Charles offered a paean to everyday Indian objects.

Design Educators of the Country

Despite not being quite what it was supposed to be, however, the Eames Report did help sow the seeds of NID’s ethos. It was on its recommendation that in 1964 the institution called for art, engineering, and architecture graduates to join its educational and training program. A good number of the bunch gathered thus would go on to become NID’s first teachers, the premier design educators of the country.

To train for their position several of them were sent to design institutions across Europe, including the Royal College of Art in London, The Royal Danish Academy in Copenhagen, and the Ulm School of Design (HfG Ulm) in Germany.

Various specialists, with and without institutional affiliations, were also brought in to help with the curriculum. Danish architect Vilhelm Wohlert and Ernst Schneidegger, a lecturer at HfG Ulm, were deputed to craft a ‘working plan’ based on the Eames Report. Others from Ulm, such as industrial designer Hans Gugelot and design theorist Gui Bonsiepe served as consultants and even collaborated with NID’s Kumar Vyas to formulate the institute's renowned foundation program.

HfG Ulm was, at the time, an influential name in radical design thinking and was thought to have taken over the progressive mantle from Bauhaus - a celebrated German art school shut down by the Nazis. Like Ulm, NID too drew initial inspiration from the Bauhaus and later decided to move away from it. [iii]

Realizing that the particular circumstances of India demanded a specific design approach, NID eventually decided to develop its own methods, without replicating existing or past pedagogical practices elsewhere.

Image courtesy: Archive Gugelot, Hamburg.

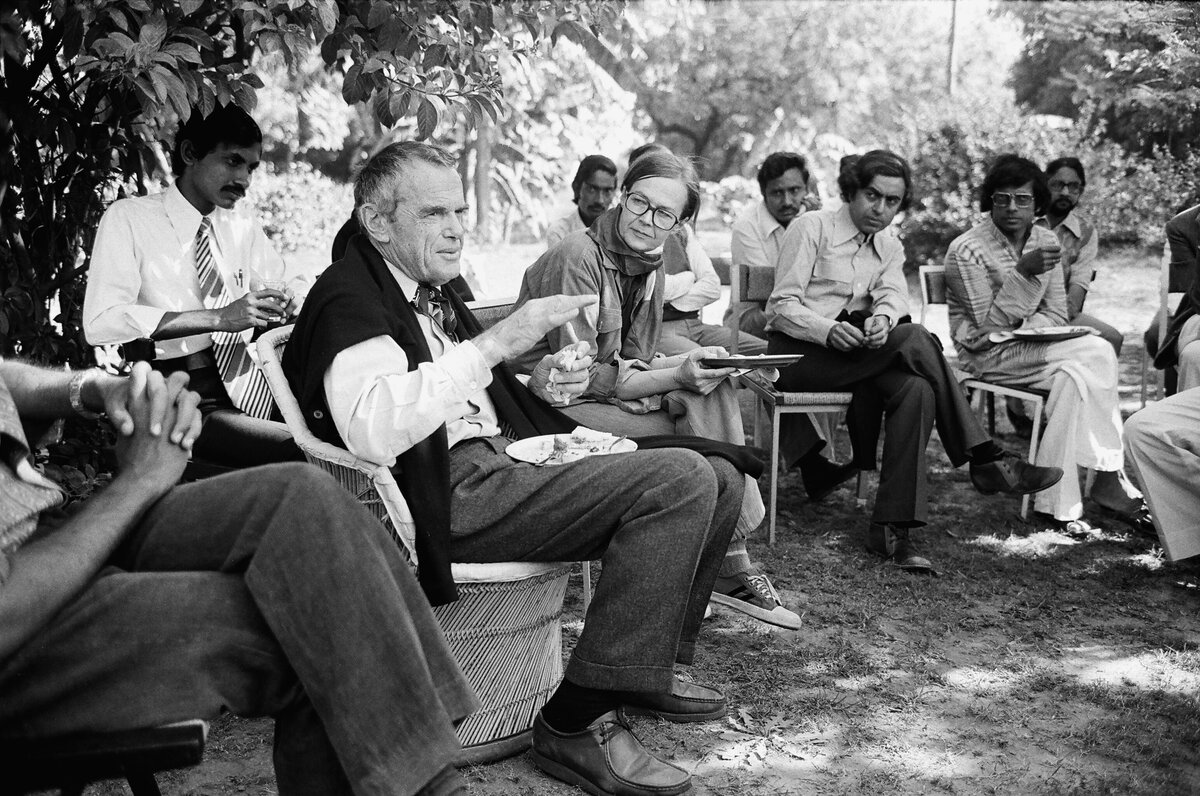

A Culture of Interaction & Exchange

Care was also taken to avoid transplanting the academic culture and curriculum of other universities via its foreign-trained faculty. Instead of reproducing the ethos of other places, effort was put into developing NID as an independent institution, with its distinctive characteristics.

Among the practices that would come to define it was a system of interaction and exchange with international specialists. Renowned design educators were invited to work and teach at the school. This included Adrian Frutiger, Armin Hoffman, Henri Cartier-Bresson, John Cage, Frei Otto, Louis Kahn and many others.

Several amongst them created new work while at the institution. American designer/architect George Nakashima (1964) and Gugelot (1968), for instance, both designed furniture with faculty member Gajanan Upadhyaya.

Design in the Hands of An Unaligned India

Nearly all these international exchanges were facilitated and sponsored by the Ford Foundation, the largest private U.S. philanthropic foundation of the Cold War era, which has since been found to have had close ties with the CIA.

They funded the Eames’ trip to India and later commissioned Wohlert and Schneidegger to distill the Eames Report. Over the years they also sponsored Louis Kahn, Ivan Chermayeff, Armin Hofmann, and Henri Cartier-Bresson’s visit to the institution. Even the cost of the faculty’s training at design schools in Europe were borne by the foundation.

Image courtesy: National Institute of Design (Archive), Ahmedabad.

Unfolding Cold War

This extraordinary level of investment by an American establishment on a design institution in India seems baffling. But the political backdrop against which much of this was unfolding was just as extraordinary.

India had emerged as a new entity in the global political landscape at around the same time as relations between the Eastern and Western blocs began to get frigid.

Not long after, in April 1955, Nehru spearheaded the Bandung Conference in Indonesia. This brought together 29 newly liberated countries of Asia and Africa in response to the bipolar politics of the Cold War. Together they announced themselves to be ‘Non-Aligned’ to either the USA or USSR. Instead they promoted Afro-Asian economic and cultural cooperation and opposition to colonialism by any nation.

Emergence of Soft Power Enterprise

This clarion call by the so-called ‘Third World’ countries, and the significant role Nehru played in it, put him and India under close scrutiny. Like with its support for various other ‘modernisation’ initiatives in India, Ford’s support for NID at this juncture has come to be seen as a “soft power” enterprise related to US Cold War diplomatic strategies.

Briefly put, these strategies were aimed at aligning a non-aligned India with the United States' version of capitalist democracy, and away from the Soviet-led communism. [iv]

Nehruvian Modernism and NID

Nehru’s admiration for the USSR, its planned economy and transformation into a world power, is well documented. India-USSR ties prospered especially after Nikita Khruschev came to power in 1953. Nehru’s visit to Moscow soon after was well received and led to the Soviet providing assistance with the Bhilai and Bokaro steel plants.

Image courtesy: Wikicommons, Bhakra Beas Management Board.

Temples of Modern India

By building such large scale plants, cities and dams - establishments he famously termed the ‘temples of modern India’ - Nehru believed India could ‘catch up’ on its ‘delayed modernity’ and be at par with wealthier nations like the U.S. and the USSR.

This vision of near-future prosperity relied in large measures on the perceived connection between design and industrial modernity. Nehru’s backing for design and architecture had its root in this understanding of their capacity to catalyze change and expedite the process of decolonization. It was this focus on design as a nation- building tool and a necessary means of industrial production that made NID (initially called the National Institute of Industrial Design) in step with Nehru’s broader developmental plans for India.

Design Culture Devoid of Criticality

The enthusiasm and spirit of innovation these plans managed to incite in young architects and designers, however, had its shortcomings. Among other things, they did not encourage or enable a ‘theoretical approach to design’. This meant that, like most other products of Nehruvian modernism, the design culture that evolved out of this moment was largely devoid of criticality or criticism.

It remained for the most part triumphantly instrumental, merely a means to an idyllic end. An end that would, in time, prove to be far from ideal. [v]

Despite this, the National Institute of Design endured, even when its international contemporaries, such as the HfG Ulm, couldn’t. [vi]

Over the years, the quality of the NID experiment has drawn global attention. In 1979, the United Nations asked NID and India to host its first design conference, which culminated in the historic Ahmedabad Declaration on Industrial Design for Development.

About two decades after, India shifted from its protected market to a liberalized, privatized, globalized one. In 2004, NID opened a new campus in Gandhinagar and another one in 2006 in Bangalore.

Over the years, the institution has turned out several distinguished graduates. Many, such as Sudhakar Nadkarni, associated with it in its early years, have gone on to contribute to important design organisations in the country. In 2014, NID Ahmedabad was officially recognized as an ‘Institute of National Importance’.

Endnotes:

[i] Quoted in Ravi Kalia, Chandigarh: The Making of an Indian City, OUP, 1999

[ii] For a closer look at these see Shanay Jhaveri, ed. Western Artists and India: Creative Inspirations in Art and Design. Shoestring Publisher, 2013.

[iii] Director of the Bauhaus Foundation, Dessau, Regina Bittner writes, ‘Both campuses were exemplary platforms in the struggle for a contemporary design attitude, which generally determined the discourses on modernism in architecture and design of the 1950s and 60s. The American architectural historian Sarah William Goldhagen speaks of “Anxious Modernisms,” of the search for creative positions in a changed global order, shaped by Western mass consumption and the emergence of welfare societies, of the systemic competition between East and West, and new alliances within the global South’. See, On Behalf of Progressive Design: Two Modern Campuses in Transcultural Dialogue http://www.bauhaus-imaginista....

[iv] Claire Wintle. "Diplomacy and the Design School: The Ford Foundation and India’s National Institute of Design." Design and Culture 9.2 (2017): 207-224. Among the many points Wintle’s essay highlights are two that need mentioning here. One, Douglas Ensminger, the first foundation representative for India, credited the influence of the Ford Foundation in India to the personal relationship he had been able to cultivate with Jawaharlal Nehru and other Indian politicians. Two, such relationships and the ‘surprisingly sophisticated’ interest that the Foundation members demonstrated in design and design education made the Ford Foundation’s role with regard to NID quite complex. While its planning and practice relating to the institution did indeed mirror the political and economic policies of the US government in important ways, in several others it contravened them. These nuances make it difficult to assign easy labels to the Foundation’s work in India.

[v] Saloni Mathur’s "Charles and Ray Eames in India." Art Journal 70.1 (2011): 34-53 See here.

[vi] A dearth of political and financial support for its unconventional methods led to the closure of the HfG Ulm in 1968.

Design Cosmopolitanism: 'Between Chairs' Exhibition, Bauhaus Dessau, 2017

The Bauhaus Lab 2017 'Between Chairs' was a research programme on global modernism at Bauhaus, Dessau. For the culminating exhibition, participants recreated the India Lounge designed by Gajanan Updhayaya and Hans Gugelot.

Read More

Furnishing a Modern India: On Architect and Furniture Designer Gajanan Upadhyaya

Known among his colleagues and students at the National Institute of Design simply as GU, furniture designer Gajanan Upadhyay, who passed away on 28th October, 2021, was considered to be the 'Father of Indian Furniture Design'.

Read More