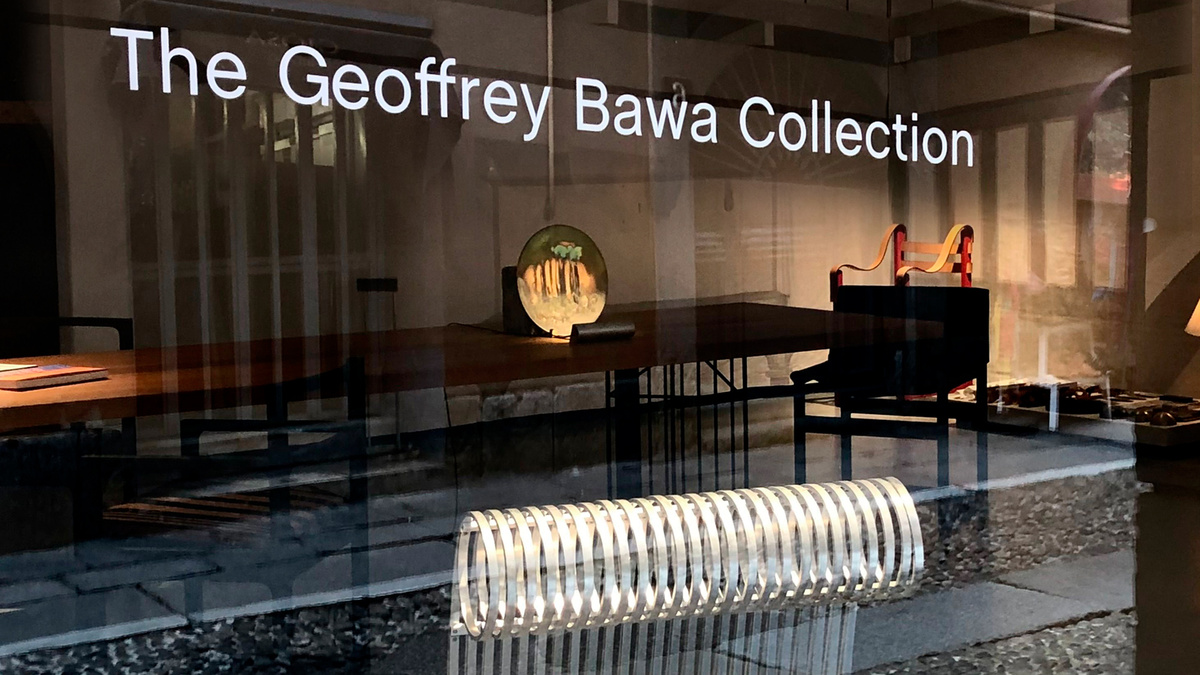

Geoffrey Bawa Collection

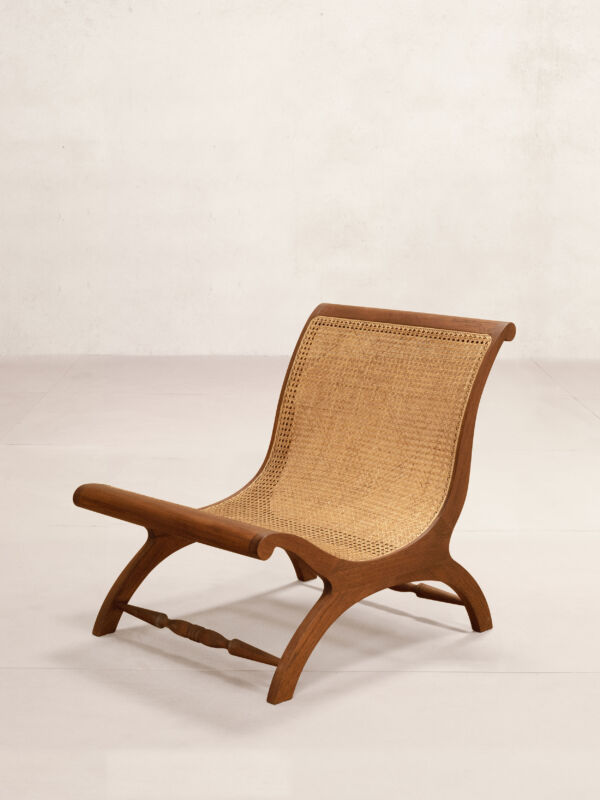

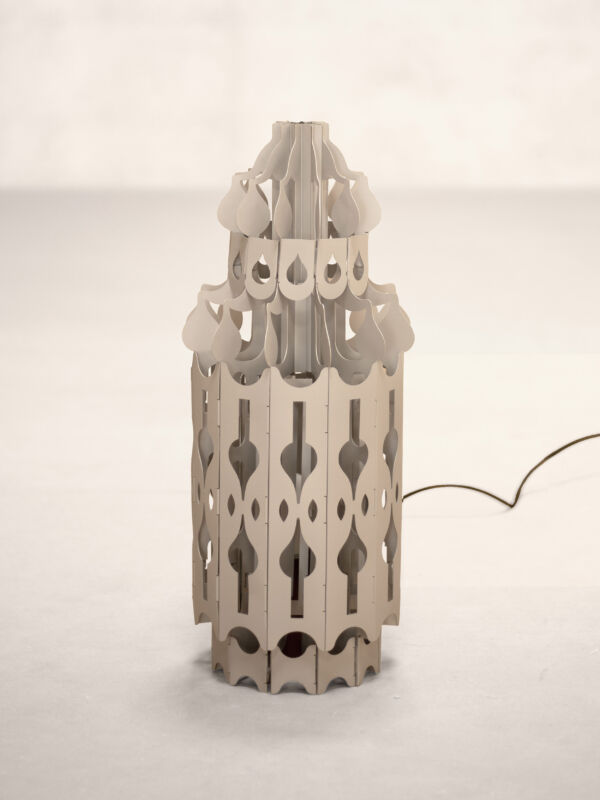

Phantom Hands, under an exclusive license from the Geoffrey Bawa Trust, has re-edited a collection of furniture, lighting and objects designed by the iconic Sri Lankan architect’s practice between the mid 1960s and mid 1990s.

Phantom Hands’ ‘Geoffrey Bawa Collection’, began with the simple mission of identifying and recreating furniture created by the architect. This posed its own unique challenges. Bawa’s designs were almost all site specific. They were also created at a distinct historical moment, and thus shaped by material and time constraints, making them deeply contextual. Removing them from their setting and reinterpreting them invariably meant assigning them new meaning. Further, many of Bawa’s pieces existed in forms best described as prototypes.

Reconstructing pieces for this collection then became an exercise in retracing Bawa’s line of thought, treating objects as insights into his design intentions rather than fixed, final products. This also meant updating production processes and using the best possible skill, technology and resources available in the present day, a far cry from much of what was available to the architect.

Bawa’s legacy rests on his sensitivity to place, context, climate, and sustainability—long before these ideas became central to modern architectural discourse. Revisiting his work thus invariably meant considering how these factors have shifted over time, from the circumstances on the planet to material availability, ethical sourcing, and environmental impact. As a result, this collection is more than a reproduction—it is a re-edition, guided by the same adaptability and awareness that defined Bawa’s original designs.