Tales From the Workshop: The Cane Weavers of Phantom Hands

Graduates of the Phantom Hands apprentice program working on chairs in the weaving unit in 2021. Image courtesy: Shamsheer Yousaf.

Parni Ray

16.12.2021

The cane weavers of Phantom Hands are a motley bunch. Predominantly women, some of them come from traditional craft communities of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Others are from the local communities around the workshop, trained via the company's in-house Cane Weaving Apprenticeship Program. Some of them are in their late teens or early twenties. Others sexagenarians.

Cane weaving is a time intensive, meticulous job. Weaving the backs and seats of even the more regular woven chairs often takes days of patient, painstaking, and careful work.

Many don't take to it. But for many others, it becomes an addiction, even a life's purpose.

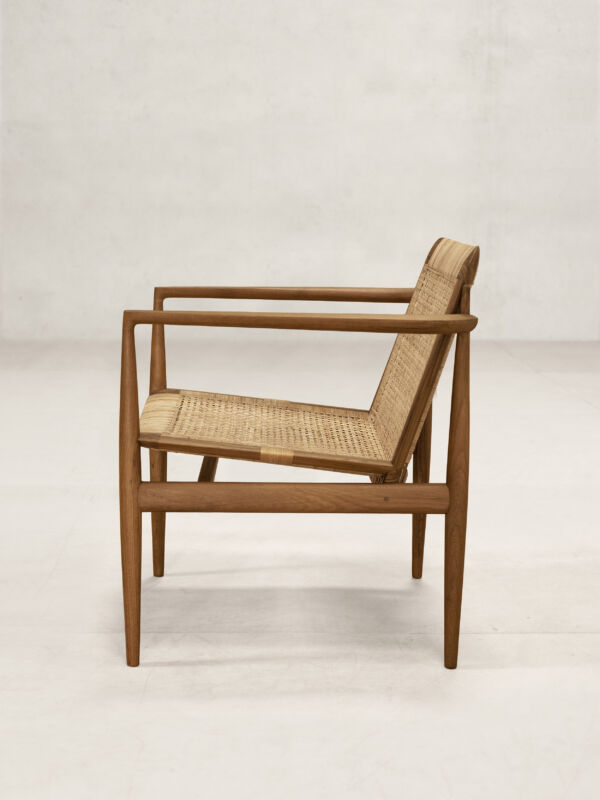

Image courtesy: Sudhir Ramachandran.

Her name is Jayalakshmi but at the Phantom Hands workshop, she is known simply as 'Cane Amma'.

She was standing under a light, inspecting the chairs she has spent weaving the week before, a commanding figure in a green-bordered white silk saree tucked at the waist.

She has recently had her cataract removed, Amma told me, after we were introduced. "Now that my sight is better I can work into my 70s, like my mother," she giggles.

At 62, she has been weaving for more than 54 years. In that time, she has made baskets, boxes, chairs, mats, pots, tables, beds, and various other kinds of furniture. Of all of these, the pieces from Phantom Hands' new Tangāli collection has probably been the hardest to weave, Amma says.

"It’s because of their curved design," she explains, running her hands around the smooth turn at the back of the Tangāli Modular Chair. "It also has a complex double weave that goes around the frame," she indicates, "the exposed back means the weave needs to be finished somewhat neatly."

All of this is time consuming. Each chair takes up to two to three full days of work, Amma says.

Image courtesy: Sudhir Ramachandran.

Labour of Love

"Once I start weaving, I don’t rest till I am done," she says. "Yes, I take my work very seriously, how can I not? What am I if not for my work? It is my purpose in life, my identity, my dignity. When I weave, I don’t want to leave any room for mistakes, I don’t want my work sent for repairs during quality checks. I want to make a perfect piece," she affirms.

There are sacrifices to be made for such a work ethic, she admits. Putting her palms up, she shows us the cuts made by the cane strands she works with. ("No no, I can’t work with gloves," she says, when we suggest a safer way to weave).

Family Tradition

Decades ago, as a young woman with children and a husband, juggling her chores and the craft was not easy. As an older woman, she had even more responsibilities. Fortunately, members of her family were almost all involved in cane weaving, so they often shared the work.

"That is how we grew up, in the midst of everyone weaving cane," she reminisces. It had not just been easy but natural to take up the craft in such a setting. Some of her cousins and brothers had even started their own business. "My brother's shop in Chennai is very well-known," Amma beams with pride.

Image courtesy: Shamsheer Yousaf.

Next Generation

The mention of the next generation inspires less enthusiasm. "They don’t have the skill," she says, wrinkling her nose. I remind her about her son who is also a weaver at Phantom Hands. She laughs heartily: "That is only until I am here. Once I am gone," she gestures to show how easily her own family might give up the trade in her absence.

But there are others from the community who she thinks do stellar work. Quietly, she points to the middle-aged man accompanying her, who is inspecting the freshly woven chairs they have just brought in. "He is very good," she whispers with mock secrecy and shakes her head, "but there aren't many others."

Image courtesy: Sudhir Ramachandran.

Material Matters

"The problem with the younger lot is that they don’t value their community’s traditional craft, the rigour it demands," Amma slips into what I gather is a common rant. "And they all work with plastic!" she says with vehemence, rolling her eyes and making us all laugh.

"Why do they do that? Is plastic better?" I asked provocatively.

She gives me a stern look. "No, plastic is not better," she affirms. ("You have touched a nerve now," the middle-aged man says, laughing).

In an endless flow of words, Amma starts describing the many ills of plastic to the young boy translating for me. He is struggling to keep up. "Material matters," he says, turning to me at some point.

Amma sits down on the chair she has been showing me to demonstrate her point; lightly bouncing on it while she delivers a monologue about how hardy cane is, how tensile, how it comes from the soil, and returns to the soil. "Cane lasts years, plastic doesn't," she says with certainty.

Image courtesy: Martien Mulder.

Future of Cane Weaving

Cane Amma hails from the traditional cane weaving community of Karaikudi, a town in the Chettinad region of Tamil Nadu. Her family, including her son and daughter in-law were the first of the cane weavers to be employed by Phantom Hands.

Initially, the three of them had been enough to meet the newly-formed company’s manufacturing demands. But as Phantom Hands grew, so did their needs, and soon the team struggled to cope with the workload.

Others from their community were then called in when required. In the meantime, Phantom Hands also tried to bring in cane weavers from closer home, from the local Bamboo Bazaar in Bangalore.

Image courtesy: Shamsheer Yousaf.

Apprenticeship Program

Neither the local craftsmen nor the fluctuating flow of weavers from Karaikudi, however, resolved the company's needs. The Cane Weaving Apprenticeship Program, conceived in 2018, was an attempt to address this need.

Originally, it was aimed at finding aides for existing weavers. The apprentices would help the in-house cane weavers to soak, peel, and cut the cane. Soon, however, the new trainees picked up the basics of weaving. Within a few months, they could weave the seats and backs of the standard chairs.

It was then that the apprenticeship program was recreated in a more organised manner. Pavithra was one of the first trainees.

Pavitra had been sitting at home after dropping out of school, fresh after her class 10 examinations. Her family was beginning to discuss marriage, "but I didn’t want that," she says. Then her neighbour who worked at the Phantom Hands workshop had brought her along one day. She tried her hand at weaving cane.

It was far from fun at first. "I didn’t enjoy it at all. I came for a week and then stopped because it seemed too tough and I thought I wasn’t interested," she says. But after a few weeks she returned and tried again. This time she stuck it out. "Then in a couple of months, I had figured it out."

Image courtesy: Phantom Hands.

Sisterhood of Weavers

That was about two years ago. Today she is a permanent employee with Phantom Hands and trains new apprentices. "I give them two weeks to begin with. Every day they learn a new weave – ginger, dabai, male-female weaving," she enumerates the names of the weaves on her fingers.

Many new trainees drop out after the two-week mark. But then many of them return, like Pavitra. Typically, they are kept under observation for three months. Then, if their work is good, they are usually absorbed into the cane weaving team.

Pavithra has taught a number of girls currently working at the workshop. She points to them as she lists their names. Some of them look up with a shy smile, others remain absorbed with their weaving.

Puja, who came to Bangalore from Nepal with her partner, is one of Pavithra’s latest students. She has just finished her third month at the workshop. At first, she too wasn’t interested in weaving, but now she has started getting into the flow. It is still hard though, her fingers still hurt at night.

Image courtesy: Phantom Hands.

Drawn to Glitch

Before starting with the weaving of the individual chairs, Pavithra was busy with quality checks. Cane quality checks involve checking finished pieces for errors in the weaving, spotting frayed or weak cane strands or any other glitch that can compromise the cane webbing. Once the error is noted, the weave is redone. "This is how I started with cane weaving," she says, "I still enjoy doing repairs the most."

Like her, most girls came to apprentice at Phantom Hands after dropping out of school, often after working elsewhere. "Mostly, people come here by word of mouth, through someone they know, like a friend or an aunty from the neighbourhood," explains Pavitra.

Although the work is not easy and has a learning curve, new trainees (typically young girls) like it here. "It’s safe here, unlike many other work places. Plus you get off days, and the pay is fixed and regular with benefits like health insurance once you are recruited," says Pavitra. This is why she recommends people she knows to come try out the apprentice program.

Pavithra was trained by Cane Amma, she tells me, as we wrap up our conversation. "It will be a while before I get as good as her, but I am proud of the work I do. When I tell people about my job here, I always mention that here in this part of the workshop, I am someone to reckon with," she signs off with a shy smile.

Featured Products

See More

Tales from the Workshop: In Conversation With the Carpenters of Phantom Hands

A chat with the carpenters of Phantom Hands about carpentry, community, learning by making, and the future of wood crafting.

Read More