In Conversation With Design Studio INODA+SVEJE: Designing Without Straight Lines

Kyoko Inoda and Nils Sveje at the Phantom Hands workshop, Bangalore.

Parni Ray

13.06.2019

Milan-based design duo Kyoko Inoda and Nils Sveje, of industrial design studio INODA+SVEJE, have spent the last two decades working with artisanal products alongside nanotechnology and mechatronics.

The furniture they make with Miyazaki Chair Factory, Japan, and Phantom Hands, India, often have a development period of two years. But that's fine, says Nils, given their final aim to keep a piece of furniture in production for at least their own lifetime and ensure a lifespan that goes beyond.

Parni Ray (PR): Both of you were trained in architecture. Kyoko you at ISAD, Milan, and Nils you at the School of Architecture at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Copenhagen. What drew you to furniture?

Nils Sveje (NS): Yes, we were both trained in architectural design, Kyoko also in interior design. But even as students we were both interested in furniture. I even had a job at the Danish Design Council Archive where my job consisted primarily of keeping order in the image archive of Danish Modern furniture. This was both educational and a lot of fun for me (laughs).

Kyoko Inoda (KI): As a duo, our attraction to furniture is related to our interest in human interaction with objects. If you look at some of the work we have done in the past with healthcare equipment, you'll notice that interaction design has been our core focus.

PR: Your design company, INODA+SVEJE took off in Copenhagen in 2000...

KI: We actually started in Milan before that. I had been living here for 6 years and Nils worked for Stefano Giovannoni. I moved to Copenhagen to develop our collaboration. While there I learnt a lot about Danish design history, wooden furniture, and the lighting culture. I frequently went to vintage furniture showrooms to see, touch and feel the size, proportion, and details of masterpieces. But after three years in Copenhagen, we decided to move to Milan.

PR: How come?

NS: We wanted to be here, it’s a beautiful country, the weather is great, and of course the food... (laughs).

PR: Fair point.

KI: We also wanted to be closer to the epicentre of Italian design, take advantage of all it had to offer. Once we got here, however, because of our proximity to the industry reality of how Italian design works or what it means, we realised that it is very different from what it had once been.

NS: We think this is because the artisans no longer enjoy a primary role in its working. What has taken precedence over their generational craft knowledge are ‘trends’ and outsourcing. This disillusioned us a fair bit, because we are not enamoured by trends. So, for a while, we did not end up working with Italian manufacturing units or companies, as we had initially intended to.

NS: I think this shifted a little bit for us when we started working with artisans in Udine (close to Venezia). And by that I mean artisan families of say maximum 10 members or so, artisan-oriented companies like those we work with in India or Japan. We were reassured that the roots do exist. We are working still to tap into it correctly as until now our Italian collaboration has mostly been for prototyping or exhibition pieces.

PR: Your work is varied not just with regard to the designs you make or the materials you use but also the production systems you use. Among the design principles you describe as inherent to the way INODA+SVEJE works is 'industrial production'. How different is this from Phantom Hands’ craft-based production system and mechatronics from handcrafts?

NS: Not different at all, not for us anyway.

PR: Is it a false opposition we just take for granted then?

NS: We think so. We find that whether we work with doctors, engineers and machine operators or artisans and carpenters, our approach is fairly the same and it involves trusting the experts, respecting their skills.

Wherever we work - Europe, Japan, India - however we work, our focus is always on optimising our designs to suit the context and emphasise the skills of those we are working with. I would say this is our strongest attribute as designers.

NS: Our methodology is very ‘modern’. We come from a background in industrial design and engineering, and you know in that context there is considerable emphasis on quantification. And we are comfortable with that given the need we are perfectly competent with computational methods.

But as designers we aren’t ourselves hung up on the quantifiable. Most people as well as designers tend to think one must make a choice between quantitative and value-based methods. We don’t. We believe in a symbiosis of these approaches. We find that this becomes especially important when working across cultures.

PR: Speaking of symbiosis, organic forms are recurrent in your work. There is a lot of curvature, texture, natural shades, play with balance...

NS: And that is what we want you to see! We are admirers of minimalism. One of the old design adages we abide by is ‘form follows function’. For both these design philosophies the description is to do little and find the ‘most simple road between two points’.

Now, technically, you could say that the shortest road between two points is a straight line. But if you look at nature for the best example of ‘form follows function,’ the shapes it throws up – sand dunes, coast lines, mountains – are never straight lines as there are more to it than just three dimensional distances.

We are fascinated by this vocabulary of the physical world and its refusal to be restrained by linearity. Which is why we are not drawn to mechanistic straight lines and prefer natural forms.

We are fascinated by this vocabulary of the physical world and its refusal to be restrained by linearity. Which is why we are not drawn to mechanistic straight lines and prefer natural forms.

PR: Among your many achievements is the Good Design Award in 2010. The term ‘good design’ of course has its own history, but what does ‘good design’ mean to you?

KI: Design that reflects its provenance, not just materially but also in terms of the labour and skill of the people who have made the object.

PR: Could you elaborate?

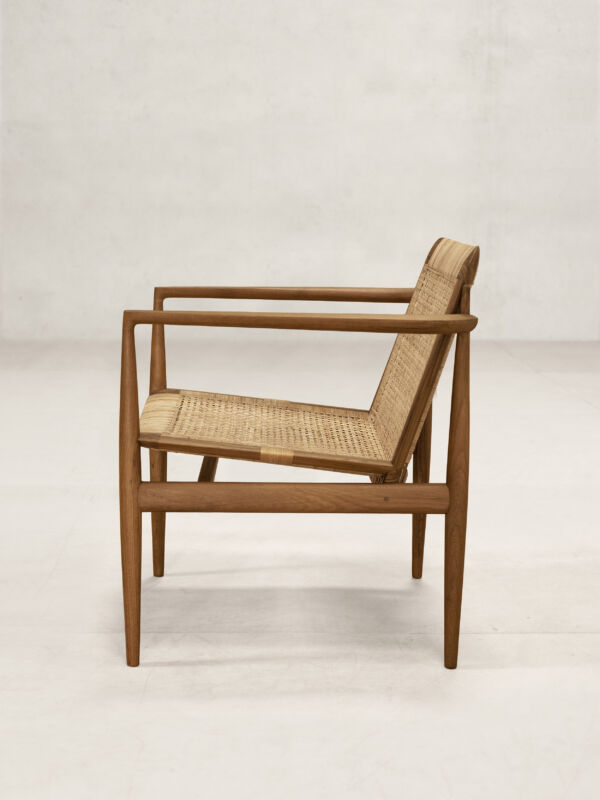

KI: When we started making furniture for Phantom Hands, we decided to leave the backs of our chair open. This exposed all the knots of the cane weaving. This is not typical. Usually people - both manufacturers and buyers - prefer a neater finish. But we think the knots convey the story of the making of the chair, which to us is important.

NS: Plus it provides the furniture a tactile identity. We may not realise it, but we all touch our furniture a lot (laughs) and the woven cane is quite pleasant to touch.

PR: Was the cane weaving something you had intended to explore when designing for Phantom Hands?

KI: Not initially. We came on board with the understanding that Phantom Hands works with teak and the wood was to be the core of our design. But once we were in Bangalore and saw the weaving process we became fascinated with it and realised it would be the cherry on top (laughs).

In part, this was because there is no European counterpart to the sort of hand cane weaving that Phantom Hands uses anymore. Much of the use of cane in furniture has been replaced by plastic, all of the weaving - whether plastic or cane - is now done by machines.

The weaving is often on moulded shapes, which are then fitted onto the furniture. So the sort of weaving you see in Phantom hands, which is done directly onto the furniture, as it is being crafted, is almost non-existent in Europe.

When we started making furniture for Phantom Hands we decided to leave the backs of our chair open. This exposed all the knots of the cane weaving. We think the knots convey the story of the making of the chair, which to us is important.

NS: Machine weaving has its advantages, of course, but it is often too refined, too precise. This takes away the particularities of hand weaving, like the knots, which tend to be unique. This uniqueness and the tactility it offers is important to our designs.

For the Tangāli Collection, we decided to emphasise this handcrafted particularity of our pieces and make borders for them. You can only make such borders by hand, machines can’t do it. We wanted to shine a light on that so our buyers know that apart from being a piece that will endure the test of time, the furniture from this collection have also been created with time, via processes that are tedious, time consuming, and can only be done with human hands.

See: INODA+SVEJE Tangāli and Mungāru Collections in our Product Gallery.

Visit: INODA+SVEJE website and Instagram.

Featured Products

See More

Behind the Scenes of the Tangāli Collection Designed by INODA+SVEJE

Designed by INODA+SVEJE, the Tangāli collection was developed over a period of nearly two years and has a distinctive cane weave pattern as its signature design element. A look behind the scenes.

Read More

Behind the Scenes of the Mungāru Gallery Chair Designed by INODA+SVEJE

A journal on the making of the Muṅgāru Gallery Chair and the process that went into Phantom Hands' first collaborative project with designers INODA+SVEJE.

Read More

In Conversation With Design Duo X+L: Simple Ideas That Last

x+l founders, Xander Vervoort and Leon van Boxtel, started their design studio in 1995. In this interview, they speak about their design journey, inspirations, and their collaboration with Phantom Hands.

Read More