In Conversation With Textile Maker Ravi Khemka: In Search of the Infinite Elegance of Grey

Exterior facade of Zanav Home. Image courtesy: Mathew & Ghosh Architects

Parni Ray

10.04.2021

The Making of Zanav

When Ravi Khemka, founder of Bangalore-based Zanav Home Collection, began his career in the late '80s, he had to grudgingly join his family’s fledgling textile export company. He soon found his niche – home furnishings. It was a slow strand of the business, he had been told, but it was steady. He stuck with it till 1990 when he ventured out on his own and launched Zanav.

For

the first couple of years, he travelled around the country looking for craft-based textiles he could tap into. Finally, he put his mind and money to

building collections of home fabrics using the exquisite, but capricious, open-air exhaust vat-dyeing technique prevalent in the state

of Kerala in south India.

A long collaboration with American textile designer Myung Jin had in the meantime reinvigorated his making process. Enthused, he exhibited at trade fairs across the globe, raking up clients like Designers Guild, Zimmer and Rohde, Anna French (Thibaut), Furninova, Kravet, Schumacher, Crate & Barrel, Pottery Barn to name a few.

And then, quite out of the blue, in 2015, he hung up his boots. In repose since, he has been reacquainting himself with colour. And chasing various shades of greys.

A Metaphysical Quest for Greys

Driving away from Zanav Home Collection’s workshop, I couldn’t help but be reminded of

Jorge Luis Borges’ short story La Biblioteca Babel.

The story is set in a vast library composed of ‘an indefinite, perhaps infinite number of’

interconnected, hexagonal galleries. In this labyrinth was every book that had ever been

written, and even those that hadn’t been written yet. From the elementary to the

impenetrable, it encompassed all books, all ideas, all questions and answers. It contained, in

other words, everything.

Looking for books amidst it, however, meant rummaging through volumes of nonsense. This

was because the endless library was also arranged arbitrarily. Visitors often went mad in their

search. Some spoke of the ‘Man of the Book,’ a mythical figure who had fathomed the

unfathomable library and knew where what could be found in it. Believers travelled through

the biblioteca in the hope of finding him..

In many ways, Zanav founder Ravi Khemka’s quest is almost just as metaphysical.

Having bowed out of a thriving, two-decade-long textiles business, he has spent the last

six years developing textiles built around a singular concept of ‘grey’. Using the

temperamental open-air exhaust vat-dyeing (one of the traditional forms of dyeing, rarely used

by commercial textile manufacturers), he has ended up creating an extensive personal

repertoire of varying hues of greys.

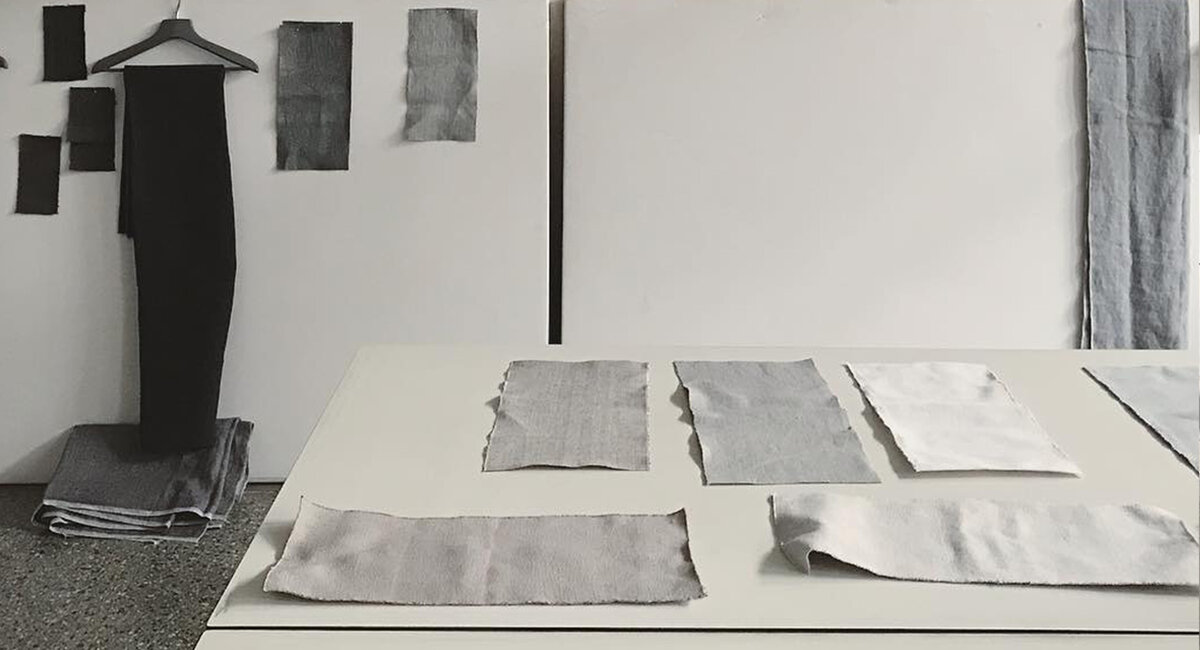

Fabric swatches from his dyeing experiments - up on his walls, shelves, tables – hover in the

background as we walk and talk in his meticulously designed workshop. Over the course

of a lengthy four hours, Ravi introduces me to his work as a textile maker, the

value partnerships have held in his professional path, and the critical role that light and place play

in his search for the perfect shade.

A World Made Up of Greys

I reached Zanav’s workshop mid-morning on a busy March weekday. It is a stone’s throw

from Koramangala, Bangalore’s hip startup hub with its snazzy cafes and bars, in a

neighborhood speckled with industrial set-ups.

Ravi received me in an enormous, well-lit office space surrounded by nothing but rows of

white shelves and tables. He is a small built, soft spoken, bespectacled man with salt and

pepper hair. Against the sparse setting, he appears stark in his slate grey t-shirt, grey pants, and white sneakers.

The palette, I quickly learnt, was not an accident - he saw no other colour.

I had trudged through the Bangalore traffic to chat with him not only about Zanav’s new

collaboration with Phantom Hands, but also to learn more about his own journey as a maker.

A cursory search on the internet about his enterprise had reaped no results. Even the list of

questions I had come armed with was arbitrary.

He nodded when I told him all of this and suggested we step outside.

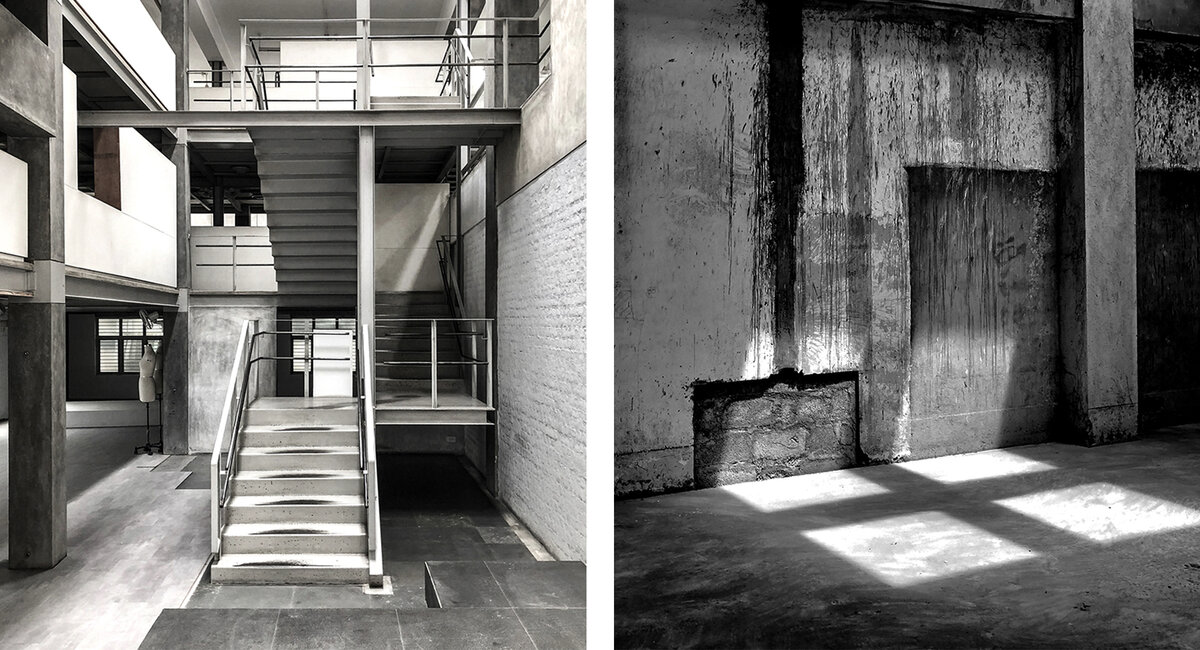

Established in the early '90s, Zanav has a history of doing business with some of the well-known companies around the world. Its present workshop, which the enterprise shifted to in

2012, is a sprawling three-storeyed structure divided in two. The building’s exposed concrete

exterior and glass doors and windows leave it feeling bare. Despite this, nothing of its inside

workings were apparent from where we stood staring at it that morning.

Right: Concept store in the making with natural light, open spaces, and exposed concrete.

Work Begins With the Workshop

"My work," Ravi says, interrupting my reverie, "begins with my place of work."

Earlier this used to be a bridal gown manufacturing unit owned by the family. It was lying

empty for some time before Ravi decided to purchase it. It now houses Zanav’s warehouse,

studio, office, a newly installed screen printing unit, and the bare bones of an upcoming

concept store.

The building is an ongoing endeavour, he explains, as we walk up. The architect who has been

working on it is one of Ravi’s longtime collaborator and a friend. "We work together because

we agree about the fundamentals – open spaces, natural light, natural ventilation" All his

collaborations, he adds, are forged on the basis of such shared predilections.

There are no rooms, no dividing walls in the vast space we are walking through. "He took them down," (referring to architect Soumitro Ghosh (co-principal of Mathew & Ghosh Architects), adding, "He also ripped out the original stairs to put in

metal ones and cut out parts of the ground on every floor to install large, square, plexiglass

skylights to bring natural light to the remotest recesses of the building."

Seamless Blending of Spaces

"The intention was to make the parts of the mammoth building blend seamlessly into each

other. I moved here because I craved a cohesive space where all the units of my company

could be placed alongside each other," explains Ravi.

On our way up, however, we see no one else. Staff members are scattered far and aside from the sound of my heels on the metal stairs, there's almost no

sound.

Soon, we are at Ravi's main work area. Sunlight gushes through the skylights. On the

large tables around lie yards of fabric in puddles. Just across is a dramatic external wall,

beams of shadow patterns its grid-like surface. They shift with the sun, changing their

position every passing minute.

Looking for Colour, Finding Light

"Light is fundamental to my new fabric collection. It brings the most out of the

minute colour variations produced by vat dyes," he says.

I hesitate about asking him about vat dyeing and what makes it special. His passion for the

craft evidently renders him incapable of imagining anyone unaware of it and I don't want to

interrupt his flow. But soon, I have to confess my ignorance.

He steps jauntily to the shelves and pulls out a bundle of yarn.

"See these?" he points out, spreading them out under the sun like a Chinese fan. "At first glance they might

seem just plain grey to you..." They are grey. But not a single grey; there are some flints in it, some

silver, some lilac, some slate. There are also other brighter shades that glisten in the sun. Yellow,

orange... and others I have no names for.

This "mesmerising ripple of colours", is the result of the vat-dyeing process, explains Ravi.

Building a Shade by Hand

The open vat dyeing is a labourious process as it involves the use of atmospheric oxygen. Yarns are

repeatedly plunged in and out of a dye bath. Each time the yarns are lifted, the dye oxidises a

little bit and transforms in colour. "This is how you slowly build a shade, in layers," adds Ravi.

Given its reliance on the largely unpredictable reaction of the dye-soaked yarn with air, vat-dyeing is almost completely speculative. Almost everything depends on the dyer. "It's the hand that predicts the results of a dyeing cycle through muscle memory gained from

years of practice. It is also the hand that creates the inconsistencies that lend vat-dyed textile

their unique colour character," says Ravi.

In effect, the dyers are the ones who create the colour.

Ravi has been working with dyers in Kerala for more than three decades. They are now master dyers

at the top of their game. It is their exceptional skill that has transformed his

experiments with colour into an unexpectedly deep exploration of gradations. "I just don’t see

colour the way I used to," he confesses.

Grey remains his starting point, his ground zero. He locates every other colour on the wheel

either amidst or in relation to it.

Ravi’s aim is to create a progression of the many gradations of grey. "As many gradations as

there can be." It’s an ambitious dream, impossible even, given that by his own

admission, every colour can be broken down into infinite intermediaries. To aim to capture the

entire range of a colour – any colour- is an attempt to trap the universe in a shade card.

Where does his quest stop? "It doesn’t," he admits with a sheepish smile, "you can

never win. It is in many ways a creative grave that I have dug for myself. I am never satisfied. I

always find room for improvement."

Scandinavian and Japanese Influences

We break for lunch. I sit across a large, white table, silently eating from the boxes of food Ravi

has ordered.

We have been talking about his childhood growing up in a small farm in Kahalgaon, in the state of Bihar. He

left home for boarding at the age of six and never returned home as he moved

from one boarding school to another until his graduation.

He speaks of the places his work has taken him to that influences his creative process and journey. Ravi speaks at length about what he has learnt

of the use of light, colour and space from Japanese and Scandinavian modernism. Even a brief

glance at his aesthetic universe is enough to appreciate the influence of both in his work.

How difficult is it to disassociate from the fabric, the colours he creates? Does he

struggle to let people do what they want with what he has made? He pauses to consider, but

doesn't answer.

"You asked me when my quest to find my colours stops and I said it doesn’t," he counters,

"that is true. But for practical reasons, for reasons of business, it often must. Having been in the midst of the making of the colours, the yarns, it is often difficult for me to

pick one over the other. To me they are all good, all a part of a bigger process. So when we

need to finalise a colour, I turn to Fabienne to make a selection," he explains.

Fabienne Collet is a Belgian weaver-designer working with natural yarns and processed work

on colours.

He credits Fabienne for, unwittingly, setting him off on his present creative journey. "A decade

ago, when we met and worked together for the first time to transform Zanav’s visual identity, the outcome was far from my expectations. There was a lot of ground to cover. But the exercise

was not in vain."

By then, Ravi had become hooked to the colour sensibility that Fabienne had introduced him to. Soon

after she left, he built his own dyeing laboratory in Kannur, Kerala for his colour research. "I

just didn’t want to depend on suppliers anymore," he says. A whole new chapter of his life opened up

soon after.

Fabienne and Ravi have worked together consistently since then. Usually she is in

India, adapting and improving on existing patterns and colours, working on new

weaves, researching on future ideas - never a quiet moment there.

A Collaboration With the Right Aesthetic Fit

Out of several of Fabienne's weaves, Bompuka, a 100% cotton upholstery fabric, has been adopted by

Phantom Hands. Like with most of Zanav’s weaves, it is produced by processes almost

completely manual and is woven on vintage looms.

"What is unique about the Bompuka is that

it brings luster and sheen, typically associated with shiny fabrics like silk, to the flat textured

surface of matte cotton," explains Ravi, "This makes it special not just as a textile but also as a

handmade, natural fibre-based upholstery."

Zanav’s collaboration with Phantom Hands is the first of its kind. At the moment they are the

only ones to have seen the new fabrics that have been produced over the last six years, jokes Ravi. The partnership was facilitated by Phantom Hands’ intention to marry contemporary

Indian textiles with modernist furniture. Zanav, on its part, was looking to reinvent

itself. After several rounds of tests, experiments and prototyping, the alliance finally became a

reality. It took two years.

But the slowness of the process doesn't bother Ravi. "Anything made with care takes time," he

says.

Ultimately, it all comes down to compatibility, the right

aesthetic fit, a shared method of working. "To answer your question, no, I don’t have

trouble disassociating from my fabric, as long as I am working with people who resonate with

me and the culture of making I believe in," he affirms.

Sitting across the large white table with his legs crossed, Ravi takes a long sip of water. "I have

poured my heart into the search for these colours," he concludes, "I should get to decide the form in

which it finds an audience."

Infinite Reflections

The sun is on the downward curve as I prepare to leave. I shake Ravi’s hand and take a long roll of fabric he asks me to deliver to the Phantom Hands office. My head is reeling

from the many shades of greys. As I get

into the car, I turn to look at Ravi's office building a last time.

Under the glistening evening sun, the glass windows and walls of his workshop reflect each other over and over again. They looks infinite.