Secrets From the Vat: The Stories We Leave Behind When We Dye

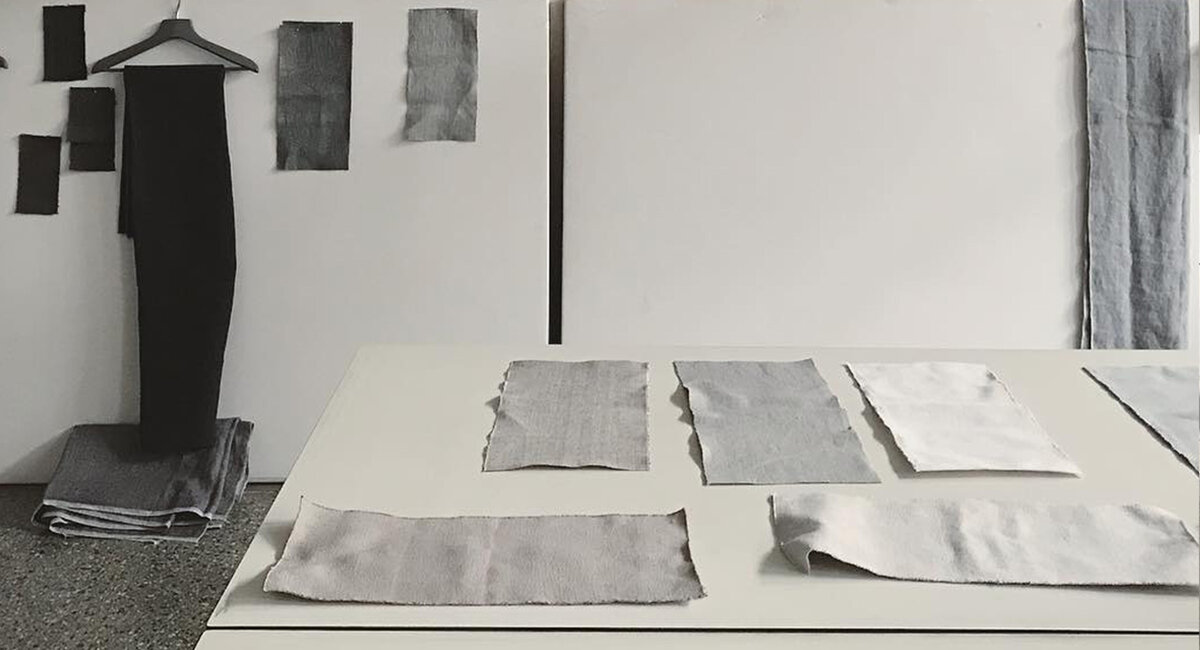

Vat dyed linen yarns from Phantom Hands textile collaborator Zanav’s dye house in Kannur, Kerala. Image courtesy: Zanav Home.

Parni Ray

27.01.2022

Traditional vat dyeing has long historical roots. The practice of soaking yarns in insoluble dyes stirred with chemicals in large vats and exposing them to the natural process of oxidation is thousands of years old. Some say the vats have magical powers, that it can give life and death. This is why the vat can produce colours like no other dyeing method can.

In India, vat dyeing has an intimate connection with indigo; under the British, it was a symbol of modern trade and oppression, and eventually, revolution. Under the hawk eye of the colonial regime, the blue dye was also extracted from its crop in vats. Native bodies, brown and sweaty under the sun, beat it until the fickle but magical blue bled from the plants grown on their soil.

Today, that blue has pervaded deep into our modern lives. But the stories of those bodies that laboured to bring us its familiar hue still remain sunk in the waters of the vat.

At Phantom Hands, we learnt much more about this process through our collaboration with textile maker Ravi Khemka. Although he doesn’t work specifically with natural Indigo, his soft furnishings enterprise – the Bangalore-based Zanav Home Collection – is one of the few fabric producers in India today to exclusively use traditional vat dyeing processes for all its merchandise.

This piece is an attempt to present a historical perspective on vat dyeing and its relevance in today's world.

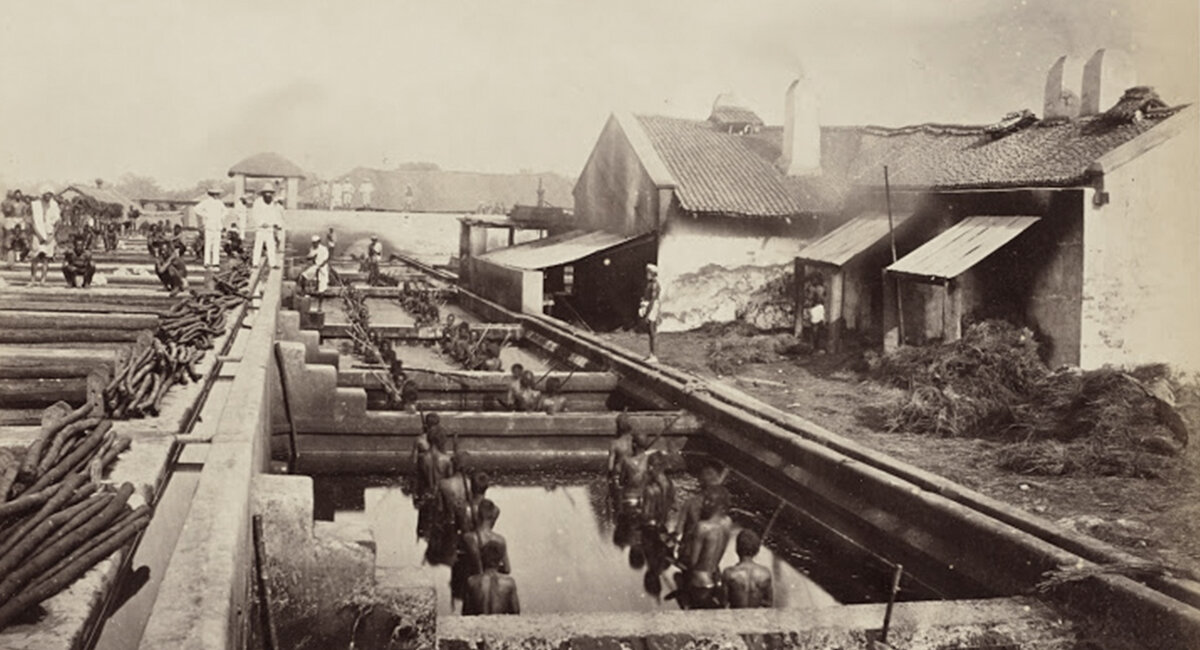

Image courtesy: www.oldindianphotos.in.

It was 1854 and Colesworthy Grant was writing to his sisters in England about his life in Bengal…

Whilst here, I purpose not to be idle, or unmindful of you, but, in fulfillment of that ‘good boy’ promise I made, never to neglect addressing you when practicable, by our monthly mails, to relieve the dull monotony of our usual Calcutta budget by an endeavour, at least to entertain you with a description of all I have seen….

It was almost a century since the East India Company had gained ascendancy in Bengal. In less than three years, the Sepoy Mutiny (or the First War of Independence) in 1857 would lead to the abolishment of the East India Co. and bring Bengal under the direct rule of the British Crown.

Grant was located at the heart of this action, in Calcutta, the capital of the Bengal Presidency, just hours from Barrackpore where the first stirrings of the 1857 Mutiny would break out.

Image courtesy: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS (CC BY 3.0).

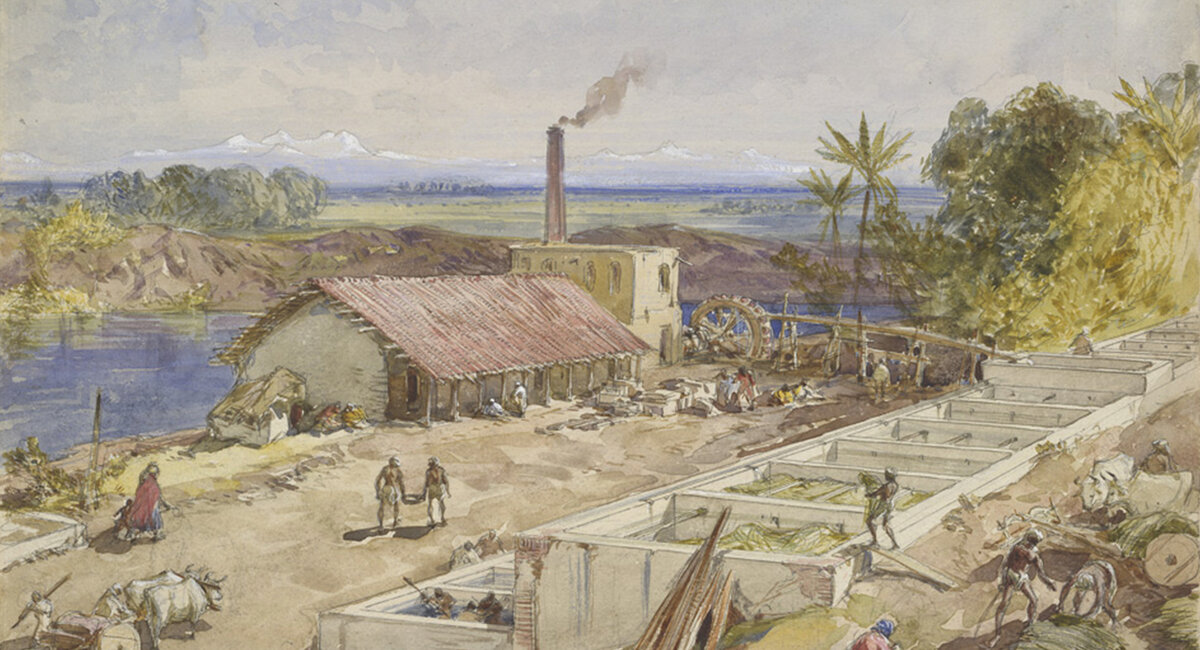

Like many British interlocutors of the time, Grant’s field notes from the colony are painstakingly thorough. As a self taught artist, he regularly supplements his descriptions with elaborate illustrations. In reporting his observations in and around Calcutta, he details his journeys up-country, the local transportation, schools, nascent towns along the Hooghly river. But most of all, he writes about the ‘culture and manufacture of Indigo,’ one of the oldest known dyes in the world.

(My descriptions are) particularly connected with the production of an article which forms one of the principal and most interesting commodity of Bengal – indigo, of which I am led to believe two thirds of our friends in England know little more than this – that it is a blue dye...

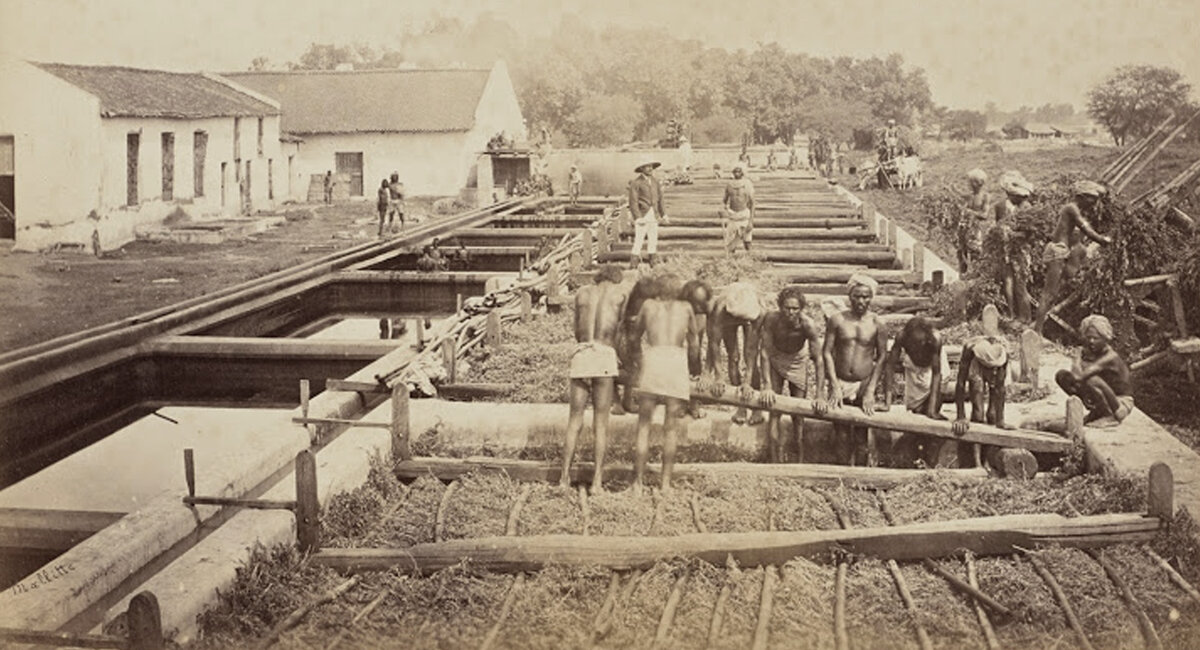

Indigo is a rich, blue colour extracted from the Indigofera plant. To derive it organically, bundles of the six-feet-tall plant were crushed and soaked overnight in vats of local river water. By morning, the tropical heat would make the plant swell up and push the level of water by over six inches. By then, the water had ‘a strange mottled appearance in colour – principally of purple and coppery hues,’ Grant notes. On its surface floated a ‘bluish froth’.

Once the temperature of the vat mixture indicated that the plants had been steeped long enough, the liquid was drained into a second ‘beating’ vat, where coolies jumped in to beat the mixture with oar-like bats, singing and crying, as the liquid changed colour from ‘orange’ to ‘bright raw green, covered with lemon-coloured cream or froth’.

Grant expends pages desperately trying to pin down the exact shades of every stage of the making of the dye. ‘I am puzzled to tell you what precise colour it really has,’ he writes, clearly at a loss.

. . . for being like the sea, exposed to the sky, in like way its quantity and the state of the weather influence its appearance. When the beating commences, however, it generally presents a light green complexion. This through a variety of beautiful changes, gradually darkens into a Prussian green, and from that, as the beating continues, and the colouring matter more perfectly develops itself (the froth having almost entirely subsided), into the intense deep blue of the ocean in stormy weather.

Image courtesy: www.oldindianphotos.in.

Fickle Phenomenon

Perhaps not surprisingly, this account of the shifting shades of indigo being processed is strongly reminiscent of the slipperiness of the colour effected by manual vat dyeing. It stands to reason, both, the extraction of indigo in a vat and the vat-dyeing itself, rely on the fickle phenomenon of oxidation.

The basics of the traditional vat dyeing method have not changed much, says textile maker Ravi Khemka. Although he doesn’t work specifically with natural indigo, his soft furnishings enterprise – the Bangalore-based Zanav Home Collection – is one of the few fabric producers in India today to exclusively use traditional vat dyeing process for all its merchandise.

For instance, for the extraction of dye from the indigo plant, vat dyeing starts by filling large vats with water (in Ravi's case, groundwater from the Western Ghats, which is special, he tells us). To this is added a requisite amount of insoluble dye (such as indigo), made soluble by the addition of a reducing agent.

Once the dye dissolves, the yarn is dipped and swirled in the vat mixture with a paddle over and over again. When saturated, the yarn is pulled out and dried until the dye oxidises and shows up as a colour, often vastly different from the one in the vat.

Later, the yarn is washed to rid it of the excess dye sitting on its surface, dried and rolled up.

Image courtesy: Swati Dandekar's film 'Neeli Raag'.

Singular Ripple of Light

Though fairly straightforward, the method can easily go off course due to the unpredictability of the oxidation process. There's little that can ascertain exactly how the dye will react with the air. A precise shade of colour (as is often insisted upon by manufacturers) is thus almost impossible to achieve via vat dyeing.

Further, because oxidation is not a uniform process, its effects show up on the yarn varyingly. The colouring of every metre of a vat-dyed fabric is of a singular instance, lending the cloth a unique effect, somewhat akin to a ripple of light.

To restrict such variance and ensure definite, repeatable results, manufacturers have been known to use various technological aids. Most of these regulate the conditions in which the final oxidation process unfolds, Ravi explains. But in his opinion, such aids rob the vat-dyed fabric of its characteristic charm, resulting instead in flat, lackluster colours.

Image courtesy: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS.

Indigo in the Realm of Power

This is corroborated by the fact that even between 1820 and ‘50, when Bengal indigo was surpassed as an export item only by opium, 2000 sq. ft. of land (and considerable labour) produced only 236 ml of natural indigo dye. But while the rate of producing natural indigo in Bengal was slow in the extreme, the demand for the dye in the Western world was rising at an exponential rate.

By the 19th C., Napolean’s Grande Armee was importing more than 1,30,000 kg of indigo a year to dye 600,000 uniforms. In the meantime, a pair of indigo-dyed cotton trousers that Levi Strauss had supplied miners during the American Gold Rush, was catching on.

Soon denim would become a crucial symbol of modern culture worldwide, which would create a further surge in the need for the blue dye.

It had in fact been in response to such developments, and the profits it promised, that the British East India Company had started indigo cultivation in Bengal. Until then the indigo crop had been grown mainly in the North Western part of the South Asian subcontinent, from where it had been exported via the silk road for centuries. In shifting its production to Bengal, the Company brought the crop closer to their immediate realm of power.

But in an agricultural context that relied almost entirely on the cultivation of paddy, this forced introduction of a foreign crop was resisted strongly. Local farmers protested the violent insistence on growing it as well as the tax that was levied on them in lieu. This resistance finally resulted in the famous Nil Bidroho, or Indigo Revolution, in 1859.

By 1897, synthetic indigo was invented by Adolf von Baeyer. But it wasn’t until 1904 that it would finally become commercially viable.

Image courtesy: Zanav Home.

Sophisticated Results From a Disappearing Craft

Vat dyeing manually, with synthetic indigo (or any other dye), is only just a little less labourious than using its natural variant. But the risks are worth it, Ravi says, because no other dyeing process produces richer, more sophisticated results.

Despite this, manual vat dyeing is a disappearing craft. Its slow pace is often considered a hindrance by manufacturers conditioned to favour speed. The irregularity of its final result is similarly a deterrent for markets that tend to hail homogeneity.

What has kept vat dyeing alive is the generational knowledge of the communities that practice the craft. Besides possessing the secrets of regulating the alchemy of colours, these also sustain an ecosystem of people that has emerged around the craft.

That dyeing is collective work is an integral part of the story.

Grant’s sketches convey this eloquently.

Image courtesy: www.oldindianphotos.in.

Dancing Machines

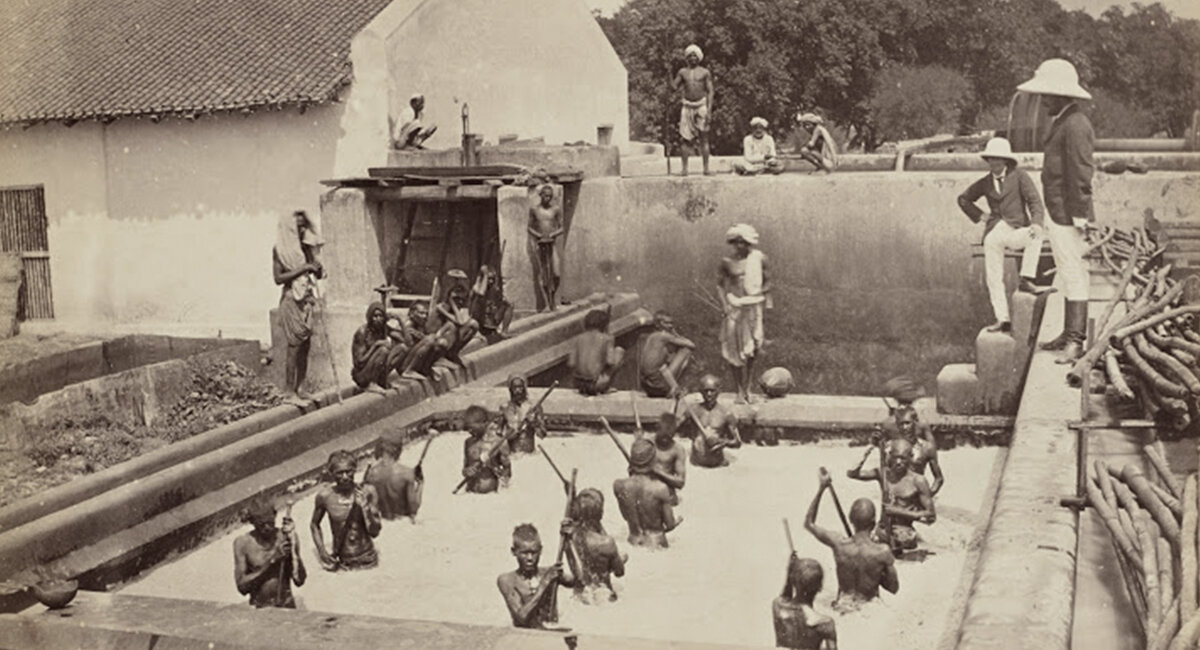

Stripped down to their waist, the coolies in his sketches are in the vat in which indigo dye is to be extracted from the plant. Their bodies are in motion, beating and stirring the vat liquid so it extracts the right amount of blue from the soaked plants. Like synchronized swimmers, their arms are in aligned postures, conveying what Michael Taussig describes as ‘dancing machines’.

Legends have it that the Bengali coolies would spit blue for a while after work. That even an egg placed near a person working in the indigo vat would be found to be blue inside when broken open.

Several stories about the vat reveal the intimate relationship between the coolies and the vat. Folklores often credit it with supernatural powers, forbidding pregnant women to be near them. Stories regarding their possession by evil spirits who sabotage the vat, induce errors and failures, abound.

Image courtesy: Swati Dandekar's film 'Neeli Raag'.

A Record of Human Ingenuity

What we take from the vats often leaves behind this material history of vat dyeing – the myths, the workers' songs, the blood and the sweat of the coolies Grant describes, the protests of the indigo farmers. Instead, only a cake of colour or a dyed cloth devoid of history, people and place is presented.

One could say that the variations in colour in a manually vat-dyed textile is a record of this past and present. A reminder that colour can never be shaken free of the memory of human toil, or the vagaries of the natural world.

References

Grant, Colesworthy (1984) Rural Life in Bengal. Calcutta: Stamp Digest. First published in 1866, London: W. Thacker and Co. (Available here).

Michael Taussig, Redeeming Indigo, Theory, Culture & Society 2008 (SAGE, Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, and Singapore), Vol. 25(3): 1–15.

Michel Pastoureau, (2001) Blue: The History of a Color. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Amiya Rao and B.G. Rao (1992) The Blue Devil: Indigo and Colonial Bengal. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

J.B. Tavernier (1925) Travels in India. London.

In Conversation With Textile Maker Ravi Khemka: In Search of the Infinite Elegance of Grey

Ravi Khemka established Zanav Home in the early '90s and supplied fabrics to leading international furnishing brands until 2015. Since then he has been chasing after a single colour - grey. Read his intriguing story.

Read More