The Palakkad Chair: An Ode to Artist Nityan Unnikrishnan’s Long-standing Bond with Furniture

Image Courtesy: Chatterjee & Lal Gallery, from their booth at India Art Fair 2023

Nilofar Haja

06.09.2023

It all started in 2013 with a birthday gift. Based then in New Delhi, artist Nityan Unnikrishnan, designed a wood-and-cane chair inspired by George Nakashima, as a gift for his friend. Now, almost 10 years and several iterations later, that chair has evolved, through a collaboration with Phantom Hands, into the Palakkad Chair.

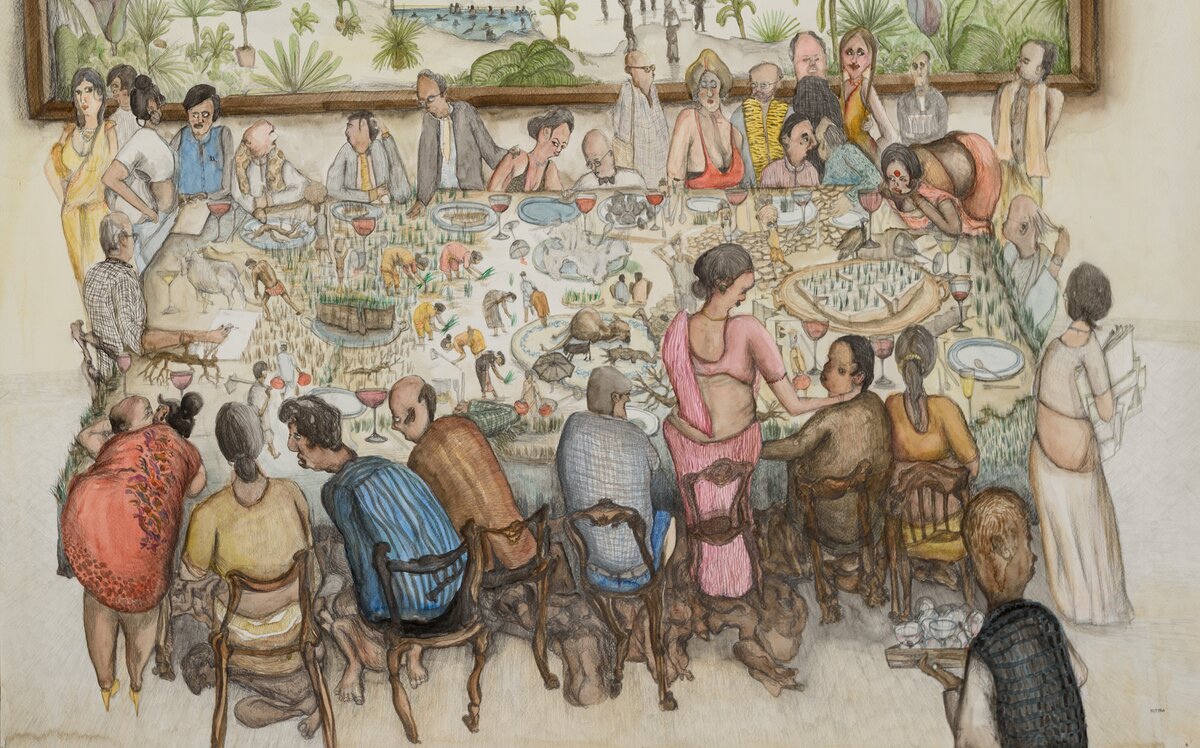

Furniture forms a persistently-innocuous imagery in Nityan Unnikrishnan’s paintings. Transitional-style chairs, cupboards, bureaus, and stools lie strewn, toppled or occupied by people; acting as a narrative device as well as pinning down the story in a particular time and milieu. “I make characters out of the furniture, which is partly due to my design background, but also because I like these objects and they mean something to me,” explains the artist.

This profusion of furniture can be attributed to Nityan’s time at the National Institute of Design (NID), Ahmedabad, but also to his childhood. Growing up in the coastal town of Kozhikode, Kerala, ‘wanting to be everywhere else but at school’, the artist often landed up at his grandfather’s furniture factory in Palakkad. Joyous moments were spent exploring the farmlands, playing with cattle, and later, when he was a bit older, ‘tinkering with tools in the giant shed to make pen stands, many of them’.

Nityan began dabbling with furniture design, ‘not furniture making’ as he clarifies, during his time in Delhi, where he practised ceramics for 10 years following his graduation from NID in 2002. He set up The Calicut Company in 2013 to lend a credence of formality to the designs he created for friends and clients requesting the odd bureau, side table, bed, or dining table. Scaling up this venture was the last thing on his mind as he considered it a vocation and not a serious enterprise.

(Right) 'Extra Topping' by Nityan Unnikrishnan | 2019 | Glazed stoneware ceramics and wood | 8.25 x 11 × 9 inches

So, it came as a surprise to him when Deepak Srinath, co-founder of Phantom Hands, asked him to design a chair as part of a formal collaboration. And not just any chair, but a re-edited version of the Nakashima-inspired, wood-and-cane chair Nityan had designed in 2013 as a gift for a friend. As a tribute to his grandfather’s furniture factory, Nityan christened this evolved version of his 10-year-old design, the Palakkad Chair.

To know more about the making of the Palakkad Chair, read these excerpts from a freewheeling conversation between artist Nityan Unnikrishnan and Nilofar Haja.

Nilofar Haja (NH): Your first formal collaboration with a design studio seems to have been 10 years in the making. Take us through the journey of how the Palakkad Chair came to life.

Nityan Unnikrishnan: I began to make furniture many years ago as I wanted a dining table for my home. A friend who did interior design projects in Delhi put me in touch with a bunch of really good carpenters all of whom I am still in touch with. This must have been around 2006-2007.

Over the next few years, somebody or the other would request me to design the odd piece of furniture—a side table, a coffee table, a study table, or a bureau. My design approach was very much in line with mid-century modern—it was driven into you at NID, into your bloodstream, to a point that I can’t bear it anymore.

So, yes, it continued in this way, with the small projects for friends and their friends. Then it started to look like I had a portfolio, so I set up The Calicut Company in 2013. In the same year, I made a wood-and-cane chair, based on the George Nakashima chair at NID, as a birthday gift for a friend. This was the first iteration of the Palakkad Chair.

Right about that time Deepak was setting up Phantom Hands. I knew him through Aparna (Rao, a fellow NID graduate and co-founder of Phantom Hands) and I would ask him for guidance about my furniture venture. Over the years, we had a lot of casual, meandering conversations about our work and Deepak would always ask me if I had worked on new designs. I guess (the) subtlety is completely lost on me!

It was only in 2021-2022 that Deepak directly talked about wanting to make furniture with me. When I went to Bangalore in early 2022 I was quite awestruck by the scale of his workshop. I had not seen anything like that. The last factory I had been to was my grandfather’s which had pythons and fallen trees.

NH: How did the Palakkad Chair take shape when you first designed it?

Nityan: I have always admired George Nakashima and he was on my mind a lot in those days (in 2013) because he was a craftsman-designer, and I could relate to that because of my ceramics work. At NID, his furniture was strewn around all over the place and we would frequently sit on his chairs. You could even buy his chairs and furniture by other established designers, at the Sunday Market in Ahmedabad.

The talented carpenter I was working with in Delhi, Kamruddin, would often make single pieces for me. We had worked together for about seven or eight years by then, and I appreciated the fact that he was great at reading drawings—a prerequisite to working with designers. He spent a month on the chair and it turned out alright. A cane weaver wove the seat and though it had some minor finishing issues, it was a good piece overall.

NH: What has changed in the iteration you created with Phantom Hands in 2022?

Nityan: We had no access to the chair that was made 10 years back. I had no drawings of it, not even sketches, so I began by drawing it again from memory, in a way. The prototype I made was clunky; the seat had a patterned weaving and the wood had a dark-stained finish. This design went through a few iterations and refinements. For instance, we experimented with the design and detailing and pared it down to a simple, clean aesthetic.

The spindles evolved to become the main character of the chair. The spindles on the back might remind you of the headrests from old four-poster beds or baby cots that were common in Indian households, until recently when they have suddenly become antiques. Lathe work and cylindrical forms are quite embedded in our crafts, across materials. All this might be a leap of imagination, but my ceramic years might have something to do with my preference for gentle and light lines as opposed to sharp, heavy lines.

We iterated on the weaving, in terms of not just aesthetics, but also working on its durability and finish. We created swatches from cotton ropes, paper and cane and saw how these materials lent themselves differently to the tactility of the chair. Finally, we decided to go with cane and used a combination of the wrap-around weave and the cross-weave for the seat.

We also focused on enhancing the ergonomics of the chair until it felt fully functional and comfortable. A lot of work was done over two years to strengthen the chair, making minor changes to the proportions, looking at variations for the woven seat—cane, cotton, jute, paper. Phantom Hands is very thorough about it and it is very helpful to have a few other pairs of eyes to look at the same thing.

NH: How collaborative was the process for you?

Nityan: Most of the work was done using a series of full-scale (1:1) drawings that I sent to the Phantom Hands workshop and we went back and forth through long-distance discussions and changes. Finally, I spent four working days at their workshop in early 2022 and that set off another set of changes which took some more time. We were all clear from the beginning that this was going to be a slow and thorough process. The workshop is an absolute dream. I don't think I could have asked for more. I see both Deepak and Aparna's touches distinctly.

NH: Does it feel like coming full circle now that you are a furniture designer?

Nityan: I will not call myself a furniture designer. I can draw nice looking things and I have the ability to make some of them work. I have seen friends, peers and real artisans at work. It is not only the fact that they make furniture with their hands but the kind of engagement they have—materials, processes, use, meaning, aesthetics—these are not seen in isolation, but as a whole. I am quite aware of my shortcomings as a designer. The other thing is that the making of this chair has, in the last three years, brought me back to sculpting, which I am happy for.

The Palakkad Chair is made of solid teak wood and features a wrap-around weave in combination with the cross weave, making the seat ergonomically comfortable. It is best suited for use as a dining chair, desk chair or as a side chair and can be purchased from Phantom Hands.