The Practical Magic of the Nakshi Kantha: A Brief Introduction

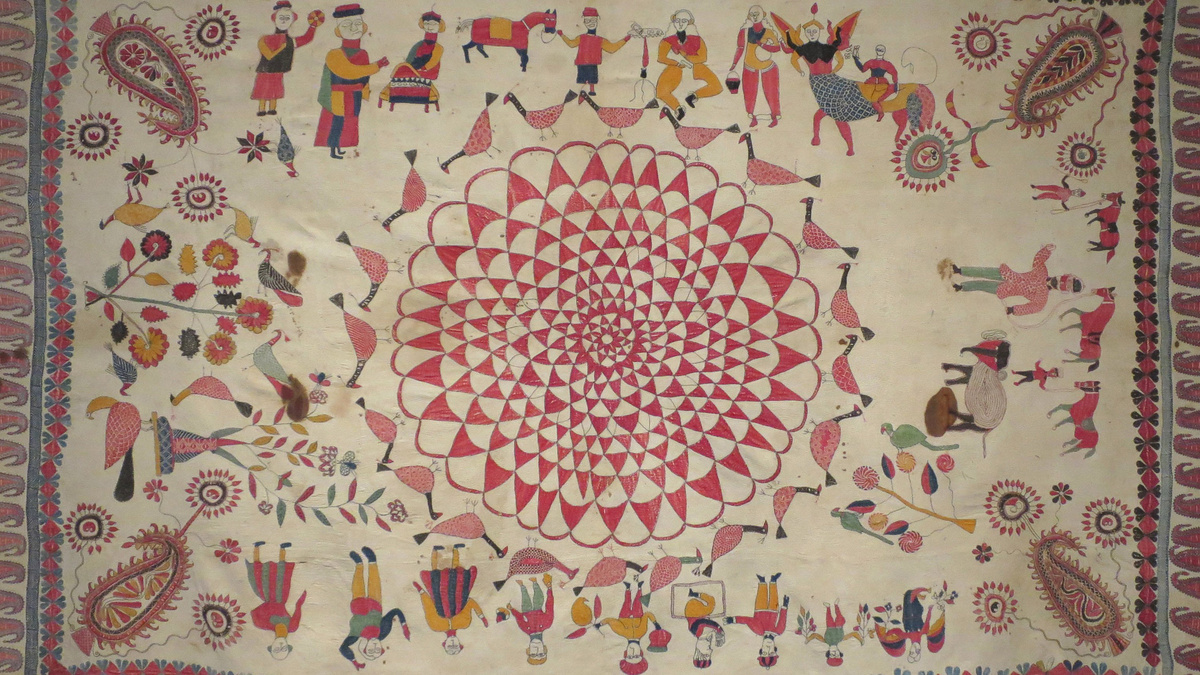

Kantha, late 19th-early 20th C., Unified Bengal, India. Cotton, Plain Weave, Embroidery. Image courtesy: Honolulu Museum of Art.

Parni Ray

30.11.2021

Born from the needles of the women in the villages of undivided Bengal, the ‘kantha’ is a humble patchwork quilt common to the Bengali speaking communities of the Indian subcontinent. Made of rags and worn-out clothes, they range from the rudimentary to the intricately embroidered 'nakshi kantha’.

A variety of stitching techniques have been known to be used for the craft. Still, the word ‘kantha’ is often used to signify the loose, long run stitches characteristic to it.

One of the oldest forms of embroidery in the South Asian region, the kantha has been resurrected from oblivion again and again. These revivals have often infused the craft with new energy, ushered in worldwide recognition, and inspired borrowings by fashion and art circles in Bangladesh, India, and beyond.

Despite the many changes that commercialisation has induced, kantha making remains a common, utilitarian craft, passed on from mother to daughter. At its core, it has always been (and still is) a frugal domestic practice used by women to recycle what they already have, and make do with little.

But kanthas are also powerful objects of affect. For ages, they have acted as repositories of the memory of their makers, their recipients, and all others who pass them along through the ages.

At Phantom Hands, we were 'reintroduced' to the kantha craft because of our collaboration with textile designer Padmaja Krishnan for the KeSa collection.

Talking about the craft, Padmaja says, "Of the many textile crafts I have worked with, kantha remains the closest to my heart. I think what I connected with most is its simplicity. It doesn’t have many stitches, just the one basic running stitch, which goes up and down. So it has a very meditative feel."

Image courtesy: Cleveland Museum of Art. Purchased with funds provided by Harry and Yvonne Lenart (AC1994.131.1).

Four stanzas into Jasim Uddin’s tragic folk poem, Nakshi Kanthar Math (Field of Embroidered Quilt), the silver-eyed Rupai falls in love with the gold-toned Saju. They meet when Saju comes asking for alms at Rupai’s door after a drought. He is a farmer, and she a farmer’s daughter from the neighbouring village across a large field.

Soon after their eyes meet, Rupai makes his way to Saju's village, her home, and eventually, her heart. They marry, start a life and build a home. Newly-wed lovers, for months their lives revolve around the joys of togetherness and the bittersweet separation induced by Rupai’s daily work in the fields. But one night, when Rupai goes to fight over a land related dispute, the parting becomes permanent. Heartbroken and home wrecked, the abandoned Saju is forced to return to her mother’s home.

Here she drowns her sorrows by stitching her embroidered quilt, or nakshi kantha. Started lovingly during her happy days with Rupai, it initially chronicled the highs of their romance – the first time they met, their wedding night, him playing his flute, their everyday games, fights, and the sweet reconciliations.

In Rupai’s absence, the quilt becomes an account of her anguish. In needle and thread, she draws scenes of the night of his departure, her broken home, her deteriorating health. She tells her mother to lay the quilt on her grave, so Rupai knows of her misery when he returned.

Long after she was gone, villagers discovered Rupai’s lifeless body next to Saju’s grave. It was wrapped in Saju’s kantha. Legends say the kantha still drifts over the field between Rupai and Saju’s village, now called the Nakshi Kanthar Math.

Image courtesy: Batighar Communication Limited, Bangladesh, 2019.

Material Culture of Bengal

Nakshi Kanthar Math was published in 1929, almost two decades before the partition of Bengal and the ensuing upheaval that would forever alter the locus of Jasim Uddin’s poems. At a moment of radical changes in the Bengali language and the emergence of modernism in Bengali literature, he embraced the role of a country poet and wrote about the simple and syncretistic life in the rural Bengal of his youth.

The nakshi kantha is a crucial component of the material culture of this setting.

The kantha is a simple covering/blanket stitched from much-washed, frayed clothes. Some say the word ‘kantha’ comes from the Sanskrit ‘kontha,’ meaning rags. Others suggest a possible connection with ‘kheta,’ also in Sanskrit, meaning a field.

Almost always created for functional reasons, kanthas range from plain to patterned and from rudimentary to fantastically ornamented. Unlike its unembellished counterparts, the nakshi kantha is a decorative quilt with embroidered patterns.

Image courtesy: Batighar Communication Limited, Bangladesh, 2019.

A Medium of Expression

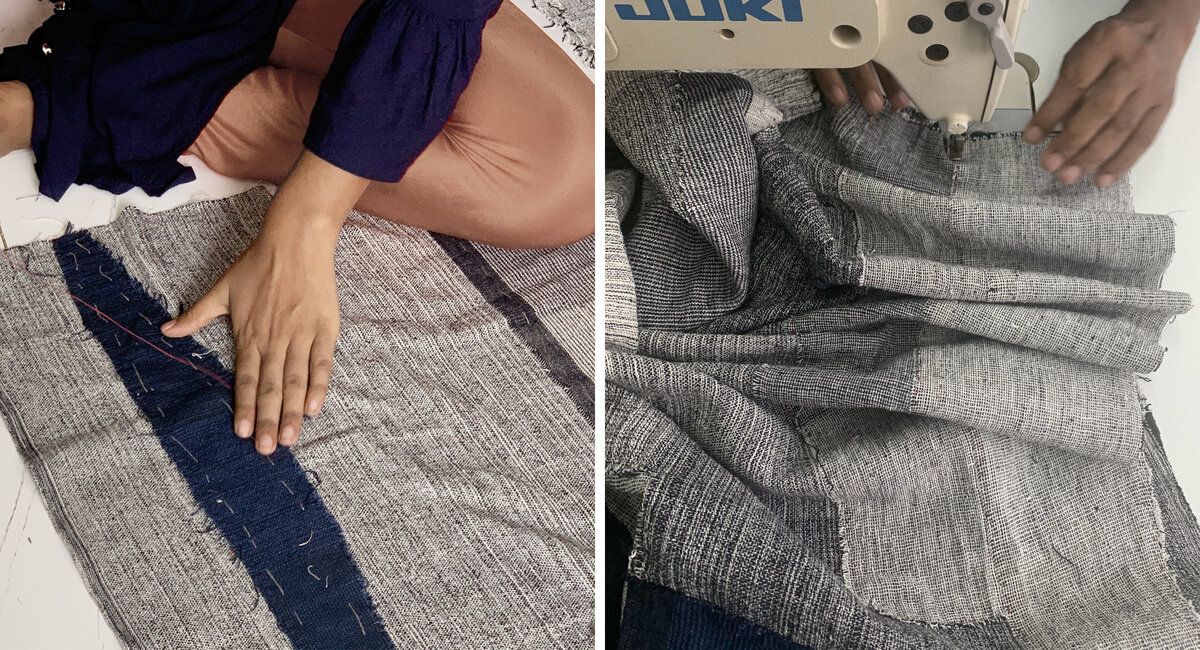

Traditionally, kantha making is an inherited skill, passed on from a mother to her daughter. Most kanthas are made of discarded sarees, but also dhotis, lungis, and even older kanthas. Once gathered, the selected pieces of fabric are layered one over the other on the ground, patched, smoothed, straightened, and then darned together in the corners and across the field.

This base fabric is then stitched over and over again with loose, long running stitches until its entire body is covered in their small, fluffy, wave-like undulations. Typically, the thread for this comes from worn-out clothes as well. The kantha maker might stick to white threads or choose colours, and other forms of stitches, to create intricate designs and pictures. These patterns or ‘nakshas’ lend nakshi kantha its name.

In a community where women were (and often still are) largely unlettered, the empty canvas offered by the kantha’s surface often becomes a space – if not the only space – to express oneself.

In ‘Nakshi Kanthar Math,’ Jasim Uddin uses Saju as a means of accessing and unfolding this realm of expression, a territory that he, as a man, likely only witnessed from afar. By gradually transforming Saju’s kantha from being a memorial of her happy times to a chronicle of her life devoid of Rupai, he highlights the kantha’s autobiographical potential.

Once merely a record of her pleasant memories, the nature of Saju’s nakshi kantha alters because it is really a record of her existence, a testament of her good times and bad, an evidence of her lived life.

Photography by: Biswajit Ghosh.

Image courtesy: Project Rangamaati.

Motifs from Folklore and Mythology

Several modern day kantha makers trace out designs on fabric and embroider them in the simple run stitch associated with the kantha style. This is convenient, saves time, and allows for standardisation of designs. Originally, however, the ‘naksha’ (pattern) on the kantha was drawn in freehand, without the mediation of any marking device and simply with a needle.

This made the shapes and figures rendered on it fairly rudimentary. Being unplanned, the nakshas also borrowed from the women’s immediate surroundings and the lives they led. Recurrent motifs such as the pagan fertility symbol of the fish, the tree of life, lotus or Hindu signs such as the swastika or the Islamic moon and stars, borrow from local folklore, customs, and religious mythology.

In such borrowings from the lived mundane, as well as the spiritually distant, the nakshi kantha is reminiscent of several craft traditions of the region. These include the Pata Chitra traditions of Orissa and Bengal and the Madhubani tradition of Mithila, Bihar, which is similarly practiced by women. In its use of more abstract decorative patterns, the nakshi kantha also has parallels with the region’s Alpana (rice flour floor drawing) traditions.

Image couryesy: Stella Kramrisch Collection, 1994, 1994-148-6805.

The Practical Craft

What sets the kantha apart from almost all of these, however, is its utilitarian value. While the Alpana, and much of Madhubani art, serves as decorations, Pata Chitras are components of narrative art forms and once served as visual devices for storytelling.

The kantha on the other hand is mainly a ‘practical’ means of staying warm or covering up, even when decorative. Following on from the traditional caretaking role of their makers, they are used primarily as a means of protecting – whether objects or people – by enclosing them.

The many variants of the kantha are put to different uses. Besides serving as blankets in the cooler months, they are also used as a cover for seating areas, a wrap for keeping jewellery, as a prayer mat, and for several other purposes, both secular and religious.

The soft texture of their cloth make kanthas ideal wraps for newborn babies, the purpose they are used for most popularly. This association with children, specifically their birth and early years, lends kanthas considerable affective value and makes them potent heirlooms, transmitted through a family for generations.

Tactile Intimacy of Kantha

'These recycled textiles have been imbued with extraordinary potency, entangled with the intimacy of touch and its transfer from one set of hands to another,' writes Pika Ghosh in her book, 'Making Kantha, Making Home: Women at Work in Colonial Bengal'.

Stains, patterns of wear, and other physical traces often intensify the affect they embody and come to represent relationships and emotional connections across distances and generations. 'Kanthas are endowed with the ability to make houses into homes, usher new life into the world, give comfort in faraway places, connect individuals and renew relationships,' points out Pika.

Threads of Life

This ability to sustain is integral to the material reality of the kantha. Being a tangible token of the past, it is a potent means of sustaining memory, be it of the community or the individual. For several women whose personhood is regularly lost in daily domestic tribulations, it is also a means of sustaining a creative self.

But aside from this, the form of the kantha, its composition from materials considered worn, shabby or destroyed, also allows it to sustain a chain of textile making. Much like the eternal yogurt, which can (theoretically) continue through generations, the ingredients of the kantha is a powerful symbol of the endlessly unrolling threads of life.

Says designer Padmaja Krishnan, "There is something poetic about the fundamental philosophy of the kantha. To take something torn, wasted, and discarded, and to make something new with it, something more than the sum of its parts is both hopeful and empowering."

An Inhabitant of the Environment

Despite this philosophical heft, the use of the kantha in households is prosaic, everyday. Therefore, Jasim Uddin’s verse aptly clings to the quotidian, carefully turning a keen eye on the regularly overlooked: the rust on the plough rendered idle by drought, the shine of the sickle tied by a string on a brown body toiling in the sun, the crunching rustle of bamboo leaves in the evening wind.

The kantha is a comfortable inhabitant of this environment. By knitting his narrative around it, Jasim Uddin captures its banal existence in the lives of those that practice and perpetuate the craft of kantha.

More importantly, however, he shines a light on the practical magic the kantha infuses in their everyday, and of others whose lives it touches.

Featured Products

See More

In Conversation With Textile Designer Padmaja Krishnan: Crafting Cloth With the Discarded

Mumbai-based fashion and textile designer Padmaja Krishnan’s clothing brand PADMAJA is known for combining traditional craft with sustainability and social responsibility.

Read More